I Feel The Need. The Need For Collapse.

Nobody likes being told they have no control.

One of the most interesting Substacks I’ve come across belongs to Robert Stack. He recently published an essay titled “No Collapse is the real Dystopia” [sic] where he talks about how chaotic the 2020s have been and how it all seems to be pointing towards cataclysm occurring before this decade is out. It’s similar to what I’ve said in my own space here in the past.

But when is it going to happen? We’re already three years into the ‘20s (where has the time gone?) and a bizarre stability seems to have taken hold. It’s not that bad things aren’t happening - they seem to have happening daily - but it doesn’t seem to be changing anything.

Robert Stark explains:

While bears have been vindicated, looking at the overall trajectory of the economy, there have been times over the past few years, when bears appeared wrong or overshot their predictions about the severity of an impending crisis. For starters, expecting that covid would cause a depression, which did not anticipate stimulus propping up the economy, at least for the time being. There was also concern, including from the mainstream media, that the Ukraine war was going to cause a global famine, the worst in modern history, by last fall. However, there was a successful deal, negotiated by Turkey between Russia and Ukraine, to allow the safe shipments of Ukrainian grain through the Black Sea. The question is whether a prolonged conflict, delaying Ukraine’s planting season, will mean a global famine within the next few years. There were also expectations that Europe would have a catastrophic energy crisis last winter, which also did not pan out. Even Russia limiting oil production did not spike oil prices as high as anticipated. Europe lucked out by having a mild winter, and enough petrol and natural gas saved up in their reserves, and extra help from America, as Biden depleted America’s strategic petrol reserves. Overall it was a combination of certain supply chain issues getting resolved from the pandemic and war, but also a decline in global demand, and just kicking the can down the road.

It’s true - a lot of bad outcomes were predicted the last few years, especially throughout 2022 with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and sticker-shock inflation at home. However, none of these predictions have come to pass, not in any significant way. Some of it was due to luck, but a lot of it was due to the fact the people in charge, deplorable as they may be, don’t just sit back and let bad things happen. In a small way, they’re on the hook for things that happen on their watch and if they can’t fix a problem, their top priority is to at least make sure events don’t spin out of control. The system will fight for nothing if not its own survival.

Stark explains how, at some point, things do need to come to a head because there’s no way for things to get better unless the current order fails. However, he also explains very astutely that we ought to all be careful what we wish for [bold mine]:

In order to have a healthier economy, it is necessary for super bubbles to pop, and a similar case can be made for social and political ills. Since the pandemic mostly exacerbated the worst trends of the 2010s, such as social atomization, the mental health crisis, the sex recession, income inequality, the establishment consolidating power, cancel culture, cultural decay, and overall cringe, the question is whether a severe economic collapse would clear out societal bullshit or just make these problems worse. An economic soft landing or stagnation scenario would likely exacerbate the worst existing trends, so I totally get the doomers and accelerationists who cheer on the collapse. However, dissidents, who are often in despair, or feel that the current system is stacked against them, have this fantasy cope, that when the big collapse occurs, either they or their ingroup will do better or be liberated from systems of oppression, which is incredibly naïve. Dissidents have no institutional power and this doomer mentality is very passive, primarily fulfilling a psychological need. If one’s life and inner psyche is in chaos, one tends to want to see the cold indifferent society around them collapse as well.

This is exactly what I’ve been saying concerning the motivations behind the collapse as well as civil war discourse. So much of it’s rooted not just in fantasy, but a desire for something extraordinary to happen in their lives, or outright hatred; hatred of how their lives have turned out, hatred of what’s become of the world around them, and hoping it all comes crashing and burning down so they may revel in the failures and sufferings of others.

I get the sentiment. Our problems are real and I’d be lying to you if I claimed I’ve never wished a horrible fate to befall the people who’ve brought us to this place and those who stand beside them. But if a collapse were to occur, the idea it’d hurt only our enemies and never ourselves is naivete. It’s like being in a building full of things and people you hate catching fire, yet thinking you’ll manage to avoid getting burned, despite being stuck inside like everyone else.

A collapse would be so devastating, it’d affect all of us adversely. I don’t believe we’re headed for a collapse any time soon not just because that’s what the evidence tells me, but because there’s no use in predicting such a thing. Really, if someone told you everything we know will come to a crashing halt sometime in the next few years, how would you react? How could you ready yourself for something like that? Sure, you can “prep” all you’d like (you should always be prepping, anyway), but once the collapse comes, you’re not going to have any control over what comes next. Not to mention few of us have any frames of reference with which we can use to keep events in perspective and maintain our sanity. Buying guns, ammo, emergency food supplies, and homesteading definitely helps get you through the dark days, but the objective is to eventually see the re-establishment of order, not to live in a perpetual state of anarchy and chaos.

Imagine the United States collapsed like the Soviet Union did in 1991. What then? Sure, a new geopolitical order will eventually be established, but what will life be like? How do you live through something like that? At some point, speculating these worst-case scenarios becomes an exercise in futility because the nature of collapse is uncertainty. It’s like playing the “what-if?” game: you assess there are far too many risks, eventually concluding doing nothing might be the better choice, in turn calling into question the utility of contemplating worst-case scenarios in the first place.

In case you couldn’t tell, I’ve about had it with doomerism. There’s just no point to it. Prepping involves contemplating the unthinkable, but it also involves dealing with the mundane - like extreme weather - and the advice is useful in both good times and bad. Doomers, however, have nothing to offer beyond dramatic predictions of catastrophe. Hey, your country is going to collapse Soviet-style in a few years and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Enjoy! The commentariat is full of people who make a living and a name for themselves saying these sorts of things, while offering little in the way of evidence, beyond coming up with historical parallels that seem to fit current events. Not only is history more unique than some of us like to give it credit for, however, it could be a lifetime before any of us are vindicated in our predictions. During that time, a lot of things can change in the process. It always does. History doesn’t unfold in a straight line.

Yet it all has to come to a head at some point, right? Nothing lasts forever, anyway. That’s true, but there’s just no predicting when and there isn’t much use in doing so. For one, America is clearly in decline, but collapse isn’t always the end result. If nothing else, the inevitable not only can be delayed, but it can be delayed into perpetuity.

Stark explains:

Doomers rely upon this fantasy that one external shock to the system, or Black Swan event, will cause the entire system to come crashing down like a house of cards, but the system has shown itself to be much more resilient than that. California shows that a one party liberal hegemonic system can last much longer than one would think, though it has been sustained by Silicon Valley revenue, and the exodus of the middle class acting as a safety valve for discontent. The financial propagandists who talk of a soft landing are partially correct, in that it is a soft landing or no recession for those at the top. In fact, America is working great for the people who run it, but not for those with no power and influence. The incoming severe recession may just mean more urban blight, homeless encampments, increased deaths of despair, and widening income inequality, but not necessarily a collapse of institutional power.

This is where I need to remind everyone: look not at historical examples from the distant past, but examples from today’s world. I’ve criticized doomers for their refusal to consider the experiences of those who’ve actually lived through collapse, hyperinflation, and the whole litany of SHTF scenarios, or for thinking these outcomes are inevitable. As I’ve said repeatedly, anything and everything under the sun will happen on a long enough timeline. Five, ten, twenty years is a long time from a human perspective, but hardly in a historical sense. If you’re going to say the U.S. is going to collapse like the Soviet Union in the next five years, have some data to back it up. They never do. They may as well try predicting the sun’s explosion.

I’d say look at Brazil and South Africa and how they just keep managing to exist despite seemingly collapsing every year. It ought to force you to re-define what constitutes a collapse or what the true outcome of a collapse is. By the time you’ve realized it’s happened, order has been restored and we’re back to the beginning of the cycle. It’s like that moment where everyone’s supposed to lose their minds and start killing each other never quite comes. I can understand how it’s frustrating, but that’s just how things happen in the real world. Life has a tendency to be anti-climactic. Even Russia has failed to collapse after their invading Ukraine and being subject to supposedly crippling economic sanctions. Even those we hate tend to be adaptable and resilient.

I wrote several entries ago about how Argentina is suffering from yet another bout of hyperinflation. You’d think after two episodes in 20 years, people would get tired of it. They probably are, but when you need to live with it, suddenly, staring the prospect of collapse in the face is no longer a theoretical exercise and your top priority becomes, “How do I get through the day?” It’s like thinking about how exciting it’d be to participate in a shoot-out and what a bad-ass you’re going to be, thinking two moves ahead of your enemy. But the moment that first bullet whizzes by, reality sinks in and you do what most people do in a shoot-out: take cover, because you don’t want to get hit and possibly killed. Not so cool now, is it?

Stark shared this screencap of a post on 4chan from 10 years ago:

The thing that gets to people and the reason I think denying them the prospect of collapse and civil war triggers such vitriolic reactions (I know, I’ve been on the receiving end) is the sense of powerlessness. That’s all it really comes down to. Nobody likes being told they have no control. They’ll try to compensate with survivalism or Live-Action Role-Playing (LARP), but in the end, these are just copes. As I said before, rarely does history present you that singular moment that tells you, “Drop everything and go crazy.”

Think back to 9/11 or the COVID pandemic, arguably the two biggest SHTF events of my lifetime - how did you react? How many of you dropped everything, marched off to war, or brought out the guns, got your buddies together, and started doing nightly perimeter patrols? Sure, some of us went on to join the military and serve in the War on Terror and, as the crisis of 2020 deepened and multiplied, many of us heightened our vigilance and raised our personal alert status.

But at least at the outset, most of us did what people have done throughout history in response to crisis: take cover and seek refuge in who and what we know. Some of us regard it as a feeble response, but this is what people do when confronted with the unknown. Anyone who says they’d do otherwise is either lying or has serious issues. As Stark explained, doomerism is prevalent among those whose personal lives are chaotic and disorderly and they’re just as in denial of reality - albeit in a different way - as the sheep who stick their heads into the sand.

The psychological needs plays such an immense role in the phenomenon of doomerism. I’ve stated in several posts that I’m not sure what’s worse: that a breaking point will eventually come, or that it never will. I’m still largely undecided, as you can tell, but I also believe that things will never have a chance to get better unless we reach a breaking point. So I definitely empathize with those who want to see things hit a breaking point, but if you learn anything from reading this, remember that what follows won’t be better - at least not for a long while - and, either way, you won’t be in the driver’s seat when it does.

One last passage from Stark:

“The nightmare is not the "collapse." The nightmare is that they pull off the End of History, and things just gradually get worse - more crime, more poverty, more degeneracy, fewer services, and a population incapable of anything other than demanding larger doses of the poison,” tweets VDARE’s James Kirkpatrick. Basically a gradual decline in people’s quality of life or a frog in the boiling pan scenario, where people just get used to degradation, and may never actually reach that breaking point but rather merely adjust their expectations and standards. Dissidents rely upon this fantasy of the masses awakening and rebellion, but with lower wages and higher unemployment, there is just greater leverage to those in power and less to the people. The political elite must factor in that some type of economic crash means that people will be desperate enough to work for little or nothing and give up their freedoms and autonomy. The question is whether Americans, especially middle class Whites, can psychologically handle the decline and transition to a post-American order?

I hope you read Stark’s entire essay and, better yet, that you’ll subscribe to his Substack. I think he’s absolutely correct in his assessment - not only will things just get worse without reaching a breaking point, even if things did, it’ll all be pretty boring in the end. As Stark explains, the worse things get, the more we become dependent on those who hold power and wealth anyway. Anyone who decides to break away from the system is going to be taking a huge risk, whether they’re actually capable of rebelling or not. And those who rebel may discover there aren’t as many of them as they thought there were.

Some of you might react to all this and say, “Wait Max, you’re a bit of a doomer yourself!” It’s true - I don’t see a bright future for this country, not for the next 20 years. I’m halfway convinced the American superpower will be no more by this time next decade. What I don’t see happening is that crashing halt - the union dissolving, hyperinflation, civil war, none of that. I just see people freaking out, mass civil unrest, and yes, violence, but eventually, people decide they’ve had enough drama, adjust their expectations and standards, as Stark put it, and get on with the task of living. 2020 was illuminating in that regard: I don’t think the real story was how unprepared we are - that’s been apparent long before - but how society ultimately goes along with whatever comes our way. Whether that’s a good or bad thing is a debate for another time.

Ironically, I’m not sure what constitutes the more doomerish mentality: thinking things will get worse, but that it won’t collapse, or thinking it will collapse, but things might get better in the end. I’m inclined to think it’s the latter, because again, we have neither a clue nor control over what comes after. If we use the example of the Soviet Union, can anyone make the argument that Russia is better off post-collapse than it was pre-? Can anyone argue that South Africa is better off today despite seemingly collapsing every few years, with another occurring as we speak? Again, it’s easy to be flippant about things you’ve never had to deal with yourself. Russians and South Africans tend not to get too excited talking about collapse like Americans do, because they lived it and it was boring and terrifying all at once. Many of them would prefer to live in America, even as it exists today.

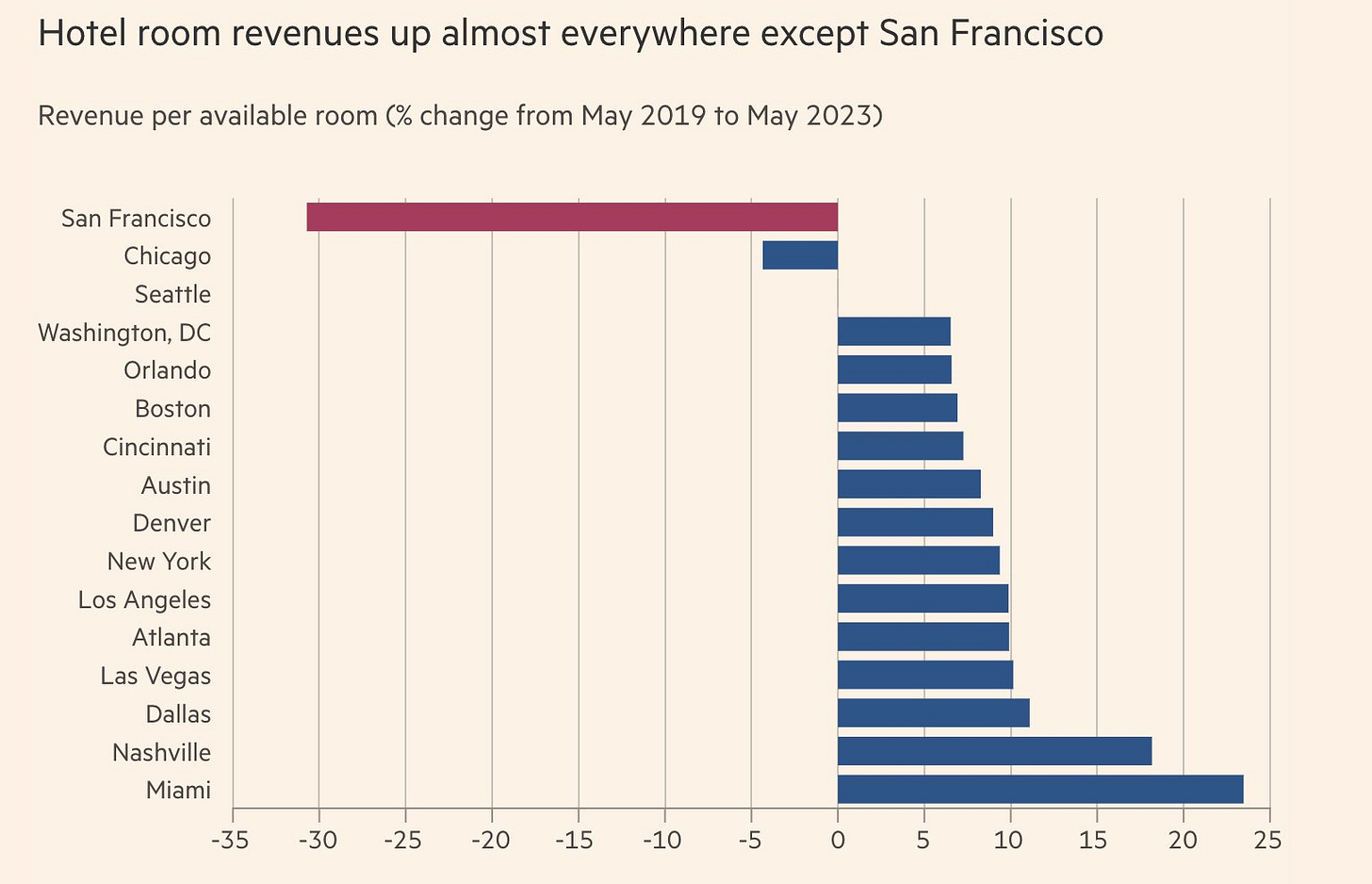

Still, one can never fall into the trap of thinking collapse is something which could never happen in America. This is the flip-side of doomerism that I suggested earlier, that It’ll Never To Us mentality. The reality is, the things we thought could never happen to us happens all the time. Just look at what’s become of San Francisco - can anyone argue it isn’t a collapsed city? The streets are occupied by the drug-addicted homeless, crime is part of the daily landscape, and major businesses are closing up shop and leaving, like the Westfield San Francisco Center shopping mall, in place since 1988. That’s not something that happens during the good times.

The days of San Francisco being a tourist attraction are long gone. Just look at how many people aren’t visiting the city, even as other cities, despite problems with crime, are seeing some kind of activity:

You can’t even get people to go out in the evenings in San Francisco, according to residents. Cities are often defined by their nightlife; if people aren’t going out after the sun goes down, what’s that say about the city? After all, if nothing good happens at night, the willingness of people to take the risk in going out at night is a good indication of the overall state of a place as any.

The point is that collapse not only can happen in the U.S., it’s already happened in one of our major cities, to say nothing of the fact it’s happened in long-forgotten and maligned regions of the country like the Rust Belt. So while talking about a potential American collapse is something which requires a heavy dose of “discipline,” to put it mildly, it shouldn’t be an entirely off-limits topic for discussion, either. Every society is susceptible to it.

I’m still running the ideas through my head. However, I feel confident in saying the 21st century, at least the second half of it, will end up being a good time for the U.S. I believe the country will live to see the 21st century and not only manage to maintain its existing form, but will add to it. Again, this is a topic of discussion for another time, but I believe we’ll manage to save ourselves from our tailspin of self-destruction. It’s just that it’s going to take a while to do so and things are likely to get worse before they get better. But the current backlash against transgenderism and Woke leftism proves that the “arc of history” doesn’t bend in one direction, as former President Barack Obama once put it.

For now, we have to confront the fact that things are likely to get worse and will continue to do so for some time. We shouldn’t confuse our belief a collapse must occur with the thought that it will. Nor should we ever assume that life will be better for us in the event of collapse, because real-world experience proves we won’t. At least, we’re not going to become the lords of a new order. If anything, we’re going to become even bigger subjects of the system. It’s going to be tough fighting a civil war if you’re spending most of your time meeting your basic needs.

Maybe it will, maybe it won’t, but like Robert Stark, I’m over trying to predict the end. If I were a betting man, I’d wager we’re still having these conversations in 2033, with collapse still just around the corner. Blackpilling as it can be in so many respects, I also wouldn’t necessarily view it as a bad thing that the “happening” never comes. It’s a gift to be able to live one’s life with a certain amount of predictability and we still have much of it in our world. And as I’ve stated ad nauseam, there’s no telling what comes after the end. It’s difficult to imagine, but things can always be worse. Imperfect stability is always better than instability.

The problem is, unless you’ve lived it, it’s hard to appreciate that.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!