Living In Accordance With Reality

One of the things I’ve come to realize is just how badly America fails at creating safe and orderly public infrastructure, even compared to less-developed countries.

The last thing I want to do is take another detour from closing out The Next 12 Months series when we’re already in the middle of February. As usual, a number of hot topics have come up in recent days that cannot go without being addressed, as it relates not only to much of what I talk about here, but also in part to The Next 12 Months. We’ll discuss these hot topics and get to some reader reaction to the first half of Part VI in this entry.

Lots to talk about, as you’ll see. Let’s begin.

Failing At The Basics

Tucker Carlson has received divisive reaction to his visit to Russia, not only for his interview with President Vladimir Putin, but his commentary on the condition of Russian society. He remarked on how much cheaper groceries are in Russia, apparently oblivious to something called “currency exchange” rates which are absolutely not in favor of the Russian ruble.

He also observed the Moscow Subway was in excellent condition compared to those of the United States, suggesting that Russia is doing something right, despite being an autocracy, despite being at war, despite being less of an economic powerhouse.

Here’s Carlson making the observation and asking the question: why is Russia’s infrastructure better than that of the U.S.?

https://twitter.com/TuckerCarlson/status/1757901280830505037

Carlson’s critics aren’t entirely wrong. Russia is far from a nice place to live. Though America has increasingly less to brag about these days, we are still arguably the single nicest place to live in the world. Russia is demographically, economically, socially, and spiritually broken. Don’t let the incredible displays of nationalism nor their inevitable victory in Ukraine fool you. I think Carlson makes a mistake many of us make: drawing broad conclusions based on a small sample size.

But Carlson’s critics are also missing something important in his commentary. Based on standard of living, the U.S. may still be unrivaled, but with respect to quality of living, not only is the U.S. in decline, it’s increasingly unable to assure safety and orderliness to its citizens, especially in its public spaces.

The New York City Subway, the biggest rapid transit system in the West, is notorious for being something of an adventure at times. Though it might be safer today than it was 30 years ago, some things about haven’t changed. It can even be argued it’s going back to being more dangerous.

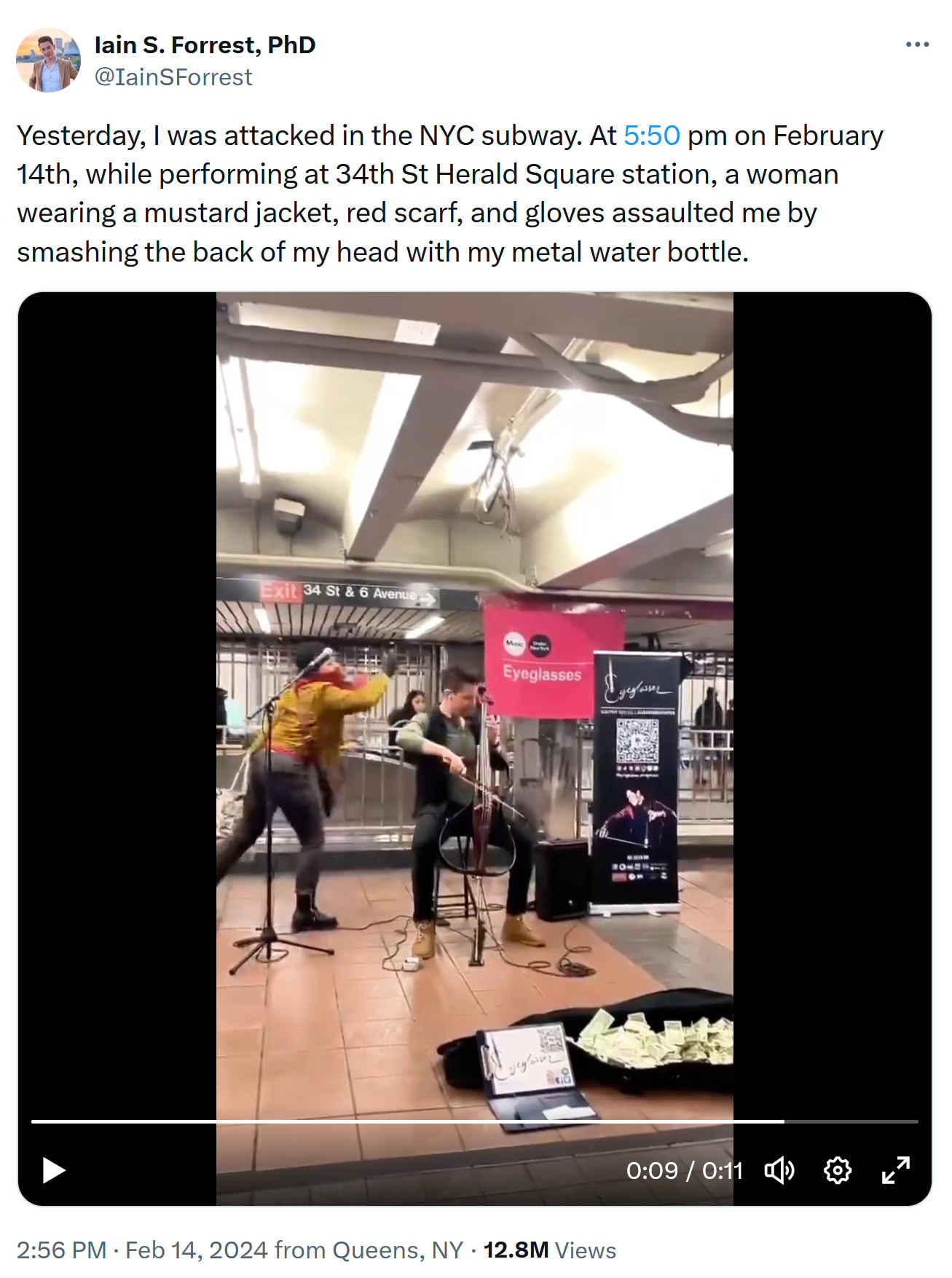

Look at what happened to a musician just the other day:

If your reaction is that this can happen anywhere, you’ve failed the test. The point isn’t that the NYC Subway is the jungle and that nothing bad ever happens on the Moscow Subway. There are bad people everywhere. The point is that some societies maintain order better than others, while some societies seem to go out of their way to court disorder. What happened to Iain Forrest is one of many examples you can find of what happens regularly on the NYC Subway.

Live long enough in Moscow or even more idyllic places like Tokyo and you’ll eventually witness something that’ll make you gasp. Yet no semi-intelligent person would ever suggest that New York and Tokyo have the same levels of crime and disorder. It’s worth noting many of Carlson’s critics are, in fact, exactly the type who’d go to Tokyo and conclude America is doing something very, very wrong.

Though the reasoning would differ, I’d also agree America is doing something wrong. I think my entire blog has been dedicated to that argument. One of the things I’ve come to realize is just how badly America fails at creating safe and orderly public infrastructure, even compared to less-developed countries. Around this time last year, I took a trip to Colombia, a place that’d been on my bucket list since my teen years. A mountainous country, Colombia’s geography isn’t suitable for rail, so the city of Medellin - notorious for being the longtime home of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar - is the only place in the country with a rapid transit system.

When I went to Medellin, this is what I saw:

Again, small sample sizes can distort perceptions. Still, is this not markedly different from what you see in most American rapid transit systems, at least in the major cities? Every station was like this, too - clean, no homeless, nobody smoking, doing drugs, or screaming nonsense. If you visit the U.S. and ride the rapid transit system of a major city, there’s a high likelihood, if not a guarantee, that you’ll see someone or something that makes you put your guard up immediately the first time you step inside a station.

Remember that Colombia is a developing, Second World country. There’s more crime, more poverty across the board. They’re still waging a diminished civil war which began in the 1960s. Yet, when it comes to the Medellin Metro and much of their public spaces, they have us beat. Mutual X follow Jenny Chan (highly-recommended) also visited Colombia and drew the same conclusion:

The point isn’t that Colombia is better than the U.S. The point is that when it comes to some of the more fundamentals of maintaining civilization, countries like Colombia seem to have a more practical understanding, while countries like the U.S. and even throughout Europe seem to have forgotten entirely what it takes to do so.

I often remark that the difference between the Third and Fourth Worlds is that the former has come to terms with the unpleasant reality of life, thereby understanding the necessity of drawing and jealously guarding boundaries. The latter, the Fourth World, hasn’t. If we view the model as more of a mindset, then it turns into a flat circle, where the First World meets the Fourth. This explains how the U.S., the most advanced civilization in history, could end up in a state of self-destruction. We’ve lost the mindset necessary to maintain civilization.

Traveling has given me great insight into not only how fortunate we Americans are, but also how much America has regressed in the most basic of ways. I think I’ve said it before, but the U.S. LARPs (Live-Action Role-Playing) as a high-trust society, despite actually being a low-trust one. When you visit places like Colombia, you really understand what it means to live in a low-trust society: everything is locked up, someone’s always eyeing you suspiciously, there are security guards everywhere, you need to pay if you want to use the restroom, the list goes on. There are certain neighborhoods you never enter, under any circumstances. The nice homes are walled off.

I’m not saying this is a nice way to live. It’s not. But it’s at least in accordance with reality. The U.S. has a long way to fall before it becomes like Colombia writ large, but what concerns me is how so many Americans are unwilling to accept reality: we are a low-trust society and we better begin acting like it. We might not survive, otherwise. I know I’ve said before that it costs us nothing to be kind in the short run, but in the long run, kindness gets taken for weakness and can get you killed. I hate to be so blunt, but this is reality in much of the world and is increasingly becoming the case in the U.S. There are things you can get away with in a high-trust society you can never get away with in a low-trust society.

If I can offer any advice, it’s to travel the world and see what life is like outside of America. Better yet, see what life is like outside the developed world. Go to places like Colombia, which is worth visiting whether you’re looking for an educational or leisurely experience. See what an enormous undertaking it really is to maintain civilization and how easily it can all be undone. See how hard people strive in these less-developed countries to maintain some semblance of order and tranquility, things we’ve come to take for granted. None of it comes for free. Our problem isn’t that we lack kind and generous souls. Our problem is decadence, an unwillingness to accept the fact that civilization is a tiny veneer to a very deep savagery that’s right underneath the surface, as Rudyard “Whatifalthist” Lynch put it recently.

With travel can come worldly wisdom. If nothing else, you’ll avoid saying stupid things like this:

Meanwhile, let’s see what stores are like in the part of the world where your hand gets chopped off for theft:

If you think I’m advocating for forced amputation as legal punishment for theft, this discussion is likely too advanced for you. My point is quite elementary, actually: if you want nice things, be prepared to pay a high price up front. Either way, live in accordance with reality.

Permissible vs. Non-Permissible Outrage

The shooting that marred the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl victory celebration has largely faded from the news, likely because of the identity of the perpetrators. Even when it was a story, however, the usual suspects couldn’t help but turn it into an indictment against gun ownership and the armed citizenry, as though they were the perpetrators themselves.

One particularly egregious take came from former U.S. soccer player turned-commentator Taylor Twellman on the Kansas City Chiefs Super Bowl parade shooting:

Where to even begin with this?

In 2014, Brazil, a country with a homicide rate three times that of the U.S., hosted the World Cup. Two years later, it hosted the Summer Olympics, where they won the men’s gold medal in soccer. Did Taylor Twellman have any issues with Brazil hosting either tournament?

He worries visitors may feel unsafe when they visit the U.S. for the 2026 World Cup. But Mexico is co-hosting, along with Canada. For at least two decades now, a low-intensity civil war has raged in Mexico and the crime rate is among the highest in the world, much higher than the U.S. Has Twellman voiced any objection to Mexico hosting the World Cup? Why not?

Remember all the moral panicking by the commentariat over Qatar hosting the 2022 World Cup? Twellman was among them. Whatever you think of Qatari state and society, there’s no question the 2022 tournament was arguably the safest in World Cup history. We may not like the way Qatar achieved the results, but that doesn’t mean the results don’t matter. The World Cup was never about regime change in a Middle Eastern country. When it came to hosting the world’s biggest sporting event, Qatar got the job done like few countries have.

So, according to Taylor Twellman-types, we should lose our minds over Qatar hosting the World Cup, but there’s no cause for concern over Brazil and Mexico, two of the most violent countries in the world, hosting it. Moreover, America should be totally ashamed of itself over mass shootings, foreigners have every right to feel unsafe coming here, and we’re undermining our case for hosting the World Cup. How does any of this make sense? It doesn’t and as I often observe, it’s not supposed to.

We all know celebrities and anyone else whose sentiments are aligned with the Regime are nowhere near as firm in their convictions as their emotional outbursts let on. But while they have a monopoly on “the floor,” we cannot allow such blatant hypocrisy to go unchallenged. A constant theme of this blog has been that America is a study in contrasts: it’s not the most violent place on the planet, but far from peaceful. Crime isn’t out of control, but order and rule-of-law aren’t in plentiful supply, either.

Nobody likes mass shootings, but anyone who’s going to worry about them ought to be even more worried about the general state of crime and disorder in the country. A visitor to America is more likely to be victimized by a common thief than they are by a mass shooter. I’ve taken a look through Twellman’s timeline; I see nothing about the robberies, smash-and-grabs, carjackings, and assaults which occur daily across the country. I know neither what’s in Twellman’s heart nor his mind, but people like him are hardly unique: they express outrage over what those in power say is okay to be outraged about. Pointing out something as obvious as the fact that Mexico is awash in crime and in the midst of a decades-long civil war can get someone like Twellman in major trouble.

The recent shooting committed by a 15-year-old Venezuelan illegal migrant in New York City, which victimized a Brazilian tourist, is a perfect example:

[Tatiele Ribeiro] Lemons, 38, who was visiting the Big Apple with her mother-in-law, previously told NBC 4 that she was standing near the cash register, holding tennis shoes she was buying as a gift when the shots rang out around 7 p.m.

She heard what “sounded like an explosion” before she felt searing pain in her leg and dragged herself to the back of the store, she recalled in the Feb. 9 interview.

Lemons was taken to Bellevue Hospital where she received 13 stitches to close the gash in her leg. She returned home to Campinas on Feb. 10.

“I believe I was born again. [It was] a bad experience but thank God. I am happy to be alive,” Lemons told the Brazilian outlet, adding that she does not plan to return to the United States “anytime soon.”

Who can blame her? Brazil has more gun violence than the U.S. Yet a touristy area of Rio de Janeiro is likely not the place someone is at risk of being shot. This goes back to the matter of boundaries and how even less-developed countries have a better understanding of their necessity than does the U.S.

Crime doesn’t need to involve guns, either. There are numerous examples of criminals victimizing tourists without needing to resort to arms. I once addressed the strange phenomenon of the Left’s preoccupation with “gun violence,” while being far less concerned with crime in general. There are two possibilities: one is that the Left (wrongly) views them as distinct phenomena, the other is that the Left is concerned about crime, but since “crime” has become such a loaded term, they substitute it with the more politically correct “gun violence” instead.

It’s been a feature of the discourse for so long, I doubt it’s going to change any time soon. It doesn’t make the hypocrisy any easier to brush off because how Taylor Twellman feels is how far too many Americans feel. Mass shootings are a part of a much larger problem of crime and social breakdown in the U.S. The shooters involved in the Kansas City incident were violent criminals; surely, they wouldn’t have shot anyone if they didn’t have guns. But it wouldn’t change their violent nature. At the risk of sounding flippant, the main reason why this shooting got folks like Twellman up in arms is because it ruined their good time. Otherwise, they could care less about the violence which occurs in America daily, with or without guns.

Clearly, they could also care less about the greater violence which occurs in other countries, who still end up hosting major sporting events. If Brazil can manage to host a World Cup without tremendous loss of life, there’s no reason why the U.S. couldn’t fare any better. What Taylor Twellman said sounds like an emotional outburst, but it also makes a disturbing amount of sense once you realize he, along with others like him, don’t actually care about violence at all.

Immigration Realism

In first half of The Next 12 Months Part VI, I remarked that there’s likely no solution to the illegal immigration crisis at present. I want to go into more depth on that.

I mentioned that Donald Trump has expressed a willingness to pursue a large-scale deportation policy if re-elected. His advisors have come up with a plan for doing so. While having a plan is better than having none, I can’t see it being implemented successfully.

Trump has repeatedly promised that, if reelected, he will pursue “the Largest Domestic Deportation Operation in History,” as he put it last month on social media. Inherently, such an effort would be politically explosive. That’s because any mass-deportation program would naturally focus on the largely minority areas of big Democratic-leaning cities where many undocumented immigrants have settled, such as Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, New York, and Phoenix.

Issues with Trump himself aside, the political resistance this plan is certain to run into would cause an impasse similar to the stand-off in Texas, this time with Democratic cities and states standing up to a Republican president. Trump would need to be prepared to go all way, including risking civil war, if this plan is to have a chance of succeeding. Are Americans prepared for that?

Both sides acknowledge this would be an effort of tremendous magnitude, with availability of manpower and resources at the heart of the matter:

In the interview, [Trump adviser Stephen] Miller acknowledged that removing migrants at this scale would be an immense undertaking, comparable in scale and complexity to “building the Panama Canal.” He said the administration would use multiple means to supplement the limited existing immigration-enforcement personnel available to them, primarily at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, better known as ICE. One would be to reassign personnel from other federal law-enforcement agencies such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the DEA. Another would be to “deputize” local police and sheriffs. And a third would be to requisition National Guard troops to participate in the deportation plans.

A dissenting view:

Even those sweeping plans understate the magnitude of the effort that mass deportations would require, Jason Houser, a former chief of staff at ICE under Biden, told me. Removing 500,000 to 1 million migrants a year could require as many as 100,000–150,000 deputized enforcement officers, Houser believes. Staffing the internment camps and constant flights that Miller is contemplating could require 50,000 more people, Houser said. “If you want to deport a million a year—and I’m a Navy officer—you are talking a mobilization the size of a military deployment,” Houser told me.

At some point, the military will need to get involved in the border situation and the issue of illegal immigration. The question is whether the president’s authority alone is enough to force necessary change. It’s one thing to secure the border; it’s another to secure the border and deport tens of millions of illegal immigrants. The former is challenging, yet feasible. The latter is likely not. It’s just too many people and there’s likely to be resistance to such an attempt, possibly in the form of large-scale violence.

That’s not to say nothing ought to be done. However, the world forces us all to be pragmatic, whether we like it or not. If we deported every last illegal alien from the country, we’d be better off for it in the long run. But there’s also a reason why these grandiose plans often don’t come to fruition or produce the intended results. Trump’s plan is likely to run into the point of diminishing returns quickly. Eventually, he’d be forced to focus his attention on other issues. No president can afford to expend all his energy and political capital on a single matter, even on something as important as immigration.

YouTuber “KaiserBauch” released a follow-up to his video titled “Why The Remigration Will Not Happen,” which drew a critical response from many. He even mentioned our friend

, who tweeted an opposing argument.Here’s KaiserBauch’s follow-up:

It sounds to me KaiserBauch is being criticized for being too much of a “squish” - insufficiently hard-line against immigration. You see this often on social media, people being criticized for not calling for mass deportation, mass imprisonment, gunning down migrants, etc. It extends to other issues, also, something our friend

is all too familiar with! I have my own strong views on what ought to be done with respect to immigration, but this isn’t the same as what’s possible here and now.It’s one of the reasons why I enjoy KaiserBauch’s commentary: it’s fact-based and, most important, practical. Criticizing him for being a squish is ridiculous, as his own commentary shows him to be well to the right. How much further right is he supposed to go, anyway? It’s one thing to be radical, it’s another to be extremist. Some of us are called extremists because we harbor a strong bias for reality, lacking any kind of idealism. We’re not talking about that here; genuine extremists tend to be detached from reality and view the entire world through an entirely ideological lens, a big reason why they’re at such odds with the rest of society.

KaiserBauch is simply being pragmatic and realistic about the situation. Mass deportation sounds feasible until you realize, in the managerial bureaucracies of the West, it’s not a simple matter of someone at the top giving the order and everyone carrying it out. It works better for some leaders, but not for others. Joe Biden has likely had the best go of it, owing to his 50 years in government and the kinship, for the lack of a better term, he’s cultivated with the American managerial state.

Trump, on the other hand, is the managerial state’s sworn enemy. A top-to-bottom purge and re-staffing of the bureaucracy would need to occur before something like his ambitious deportation plan has a chance to succeed. Such a bureaucratic takeover would be an arduous effort all its own. There’s no guarantee a second Trump administration would succeed in doing so. Then there’s the matter of where you’re going to send all the deportees to: what if their countries of origin refuse to take them back? How much leverage do we have over these countries? Again, this isn’t an argument against trying, but it’s an argument against being optimistic about the outcome.

KaiserBauch cites what Denmark did recently to curtail immigration. In many ways, the policy was a success, but not only is it the best the West can expect to accomplish, it was only possible because of a consensus within the state and between it and society. How likely do you see such a consensus forming in the U.S.?

At least among the public, a consensus appears to have emerged on immigration, with even Democrats in-sync, surprisingly enough:

Here’s the problem: public sentiment is at odds with the Regime’s interests. The Democratic Party in particular, has invested its long-term political future on mass immigration by any means necessary. Since it’s also impossible to hold anyone accountable in the U.S. managerial bureaucracy, there’s no incentive for the state to change course, either. American democracy, that thing the Regime claims to be steadfastly defending when it persecutes domestic political opponents or wages proxy war against Russia, is notorious for acting against public preference when it diverges with that of the Regime.

Watch KaiserBauch’s entire video if you have the time, but allow me to summarize his key points, which you can watch in the section “Conclusions:”

The public is against mass migration. But it’s not preoccupied by it: He notes his viewer base is predominantly Western male, aged 18 to 34, and especially concerned with migration. However, this is a specific demographic and their views aren’t necessarily indicative of public opinion overall. If the state ever chooses to address immigration seriously, it’ll do so according to majority sentiment, not according to the young male demographic. Most people are anti-mass migration, but they don’t want to break the bank to stop it, either.

Halting mass migration won’t arrest demographic decline: Immigration is no substitute for a native majority reproducing at or above replacement rate. Nor can you sustain an orderly society indefinitely through immigration. So while there may be benefits to halting migration, it doesn’t solve the matter of a people having lost the will to sustain its population organically. No matter what happens, demographic change will occur, and there are enough people here already to ensure the inevitable outcome, whether mass migration is stopped or not.

Nothing is permanent. But trends are sticky things: KaiserBauch refutes his critics who say that current trends are unsustainable by replying, humorously, that he’s not talking about what’s going to happen in the year 2453. He’s talking about the here and now. KaiserBauch’s commentary focuses on Europe, but U.S. birth rates have been below replacement level for some time now. Meanwhile, birth rates in the developing and un-developed world remain high. Birth rates among Hispanics, America’s second largest racial demographic, are higher than that of Whites. Tell me how these trends will suddenly reverse themselves in the next 20 years.

“Will” is overrated: There’s a circular argument being employed when it’s claimed that the only thing lacking when solving a problem is “political will.” The fact the will is lacking is a sign nobody in a position of power wants to do anything about it. Even with an overwhelming consensus as indicated by the poll I’ve displayed above, it doesn’t matter if those in charge don’t answer to public sentiment. Saying “all it takes is will” suggests the state actually wants to fix the problem, which it clearly doesn’t.

Be careful what you wish for: I thought KaiserBauch’s most interesting point was that anti-immigration hard-liners base their argument on a narrative where an economic collapse or war will lead to a more radicalized population and stronger, more nationalist governments. It could happen, but other things could happen instead. For example, if a war does break out, there will be a need for manpower. There are long-term repercussions in doing so, but governments will likely get caught up in the urgency of the moment and choose to retain fighting-age migrant males to staff the ranks of their armed forces. Point being, the radical right thinks that crisis will eventually straighten out priorities, but this is purely conjecture. The opposite could happen.

The Danish model or a military coup are the only choices: Only a military coup can arrest the Regime’s destabilization of society through mass migration. For reasons I’ve explained in previous essays, a military coup has a zero percent chance of occurring in the U.S., with a similar likelihood of it happening in the rest of the West (France being an exception). The fact is, what Denmark has done (again, watch to video to find out) is probably the best we could hope for, with the harder-line policies being directed at securing the border, which will likely become necessary due to it becoming an active war zone in the future. But this will take time and a major Overton Window shift to achieve.

You don’t need to like anything he says. You’re not supposed to. But that doesn’t make him wrong. It seems the Right, too, can fail to grasp reality at times.

Reaction to The Next 12 Months Part VI: Breaking Points

Due to the length of this piece, I won’t be able to cover as much reader commentary as I’d hoped. I can most certainly attempt to incorporate some of it in future posts, but I cannot make any promises.

First, we’ll go to “Nate Green.” I happen to know this person; he recently kicked off his own Substack. I hope you’ll do him a favor and give his Substack a chance, the same you gave mine.

He says:

The 80-year rule is interesting in this context because we are about 160 years removed from the last civil war (which I like to call the War of Southern Secession). And at roughly the midway point between then and now, the Great Depression was quite destabilizing, with the rise of figures such as Huey Long and Charles Coughlin being seen as especially concerning. Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan almost served as a 'deus ex machina' by finally pushing us into the rather different crisis that was World War II; what had served as another dividing line in the nation became totally unifying after Pearl Harbor.

Interesting. I think there’s definitely something to his argument that World War II “saved” the nation. Though I consider myself a part of the “America First” camp (Lindberghian, not Trumpian), I think we ought to consider what would’ve happened had the U.S. stayed out of the war. It’s quite possible internal divisions could’ve intensified to the point of a split, civil war, or revolution. I don’t want to play “what if?” (that’s Rudyard Lynch’s job!), but when you look at what was occurring around that halfway point between the end of the Civil War and now, it seems there’s indeed something to that “80-year rule” and World War II basically reset the timer.

More:

That said, I may be one of the “normies” here. A couple things that preceded the last civil war which, while not necessarily predictive, we nonetheless have yet to see this time (yet):

- The utter collapse of the two-party system. The Whigs fell apart in 1854, replaced by the Republicans, and by the 1860 presidential election there were essentially zero national parties and four sectional ones—Republicans and some Democrats in the north (candidates Lincoln and Douglas), and secessionists and unionist Democrats in the south and border states (candidates Breckinridge and Bell).

- A near-fatal assault on the Senate floor in 1856, when Representative Preston Brooks (D-SC) beat Senator Charles Sumner (R-MA) to within inches of his life.

Together, those events demonstrate the complete disintegration of the political system and of civil discourse. At the present time, we continue to at least retain a facade of both of these things; they may be tenuous but they haven't shattered yet.

Focusing on the political system, I don't know if it has to collapse before war, but that happened in 1790s France, 1910s Russia and 1930s Germany as well. Not that it gives *that* much warning time, since in the first two cases at least, the political collapse happened only months before the major violence.

So maybe I've just been rambling; wouldn't be the first time...

Nate’s not rambling. He echoes a point I’ve made since this blog began: we’ve still got a ways to go before the really bad stuff starts happening. Remember, I’m not predicting a civil war in the next 12 months, the Texas stand-off aside. I’m predicting it could occur in the next five to ten years. It’s occurrence is predicted on lots of bad stuff happening in the interim: superpower collapse, political crisis, economic downturn, etc. I feel fairly confident in saying if the U.S. manages to remain a superpower, a civil war likely won’t happen at all.

However, there’s no escaping history. If the U.S. was indeed on a trajectory to civil war if not for World War II, then it’s going to take something just as profound to interrupt the cycle once more. Except now, I’m not sure what it’d be. If we suffered a Pearl Harbor-like attack today, I doubt it’d unify the nation. It’d more likely be our undoing.

Next, we go to “Brian Villanueva:”

Your comment about the executioners of that grandfather deserving the needle struck me. I have been 100% opposed to capital punishment for decades on Christian grounds. Given that execution forecloses the possibility of repentance (and therefore salvation), and a modern state is perfectly capable of keeping someone locked up for life... capital punishment should not be practiced. I respect you and others may disagree, but that's been my view for decades: pro-life all the way, even the hard cases. I find myself wondering about that now though. We have the physical ability to keep people incarcerated, but absent the political will to do so, perhaps I need to rethink this position.

Unlike Brian, I’m not religious. I’m culturally Christian, at best. Otherwise, I consider myself the embodiment of the “post-Christian right.” As theology isn’t my thing, I’ll stick to what I’m best at: practicality.

From my experience, most criminals go through life unrepentant. To the extent they are, it’s repentance over what was denied to them. They didn’t have parents who loved them, they were oppressed, they lacked access to critical resources, the list goes on. As an empathetic person, I can relate on some level: none of us are immune to our environment. But as I’ve also emphasized time and again, few of us transform into violent criminals in a flash. We break those inhibitions down bit by bit. There are many opportunities to draw a line for yourself. By the time you’re at the point of threatening to kill people, you’re not coming back from that. Some of us are unfortunate to grow up in violent environments and I know it’s not easy to choose a better way. You cannot maintain order, however, by accommodating those who break the rules or undermine social order, regardless of their life story.

As I was drafting this piece, I came across this video of a Black woman being forced to leave a pet shop after kicking kennels containing puppies. As she leaves, she assaults two people on the way out:

https://twitter.com/Muhsoci0factors/status/1759319607398080661

I posed the question to my friend and historian Nicole Williams: how would early Americans have handled this sort of behavior? She replied, “The Scots-Irish solution is to tie her up to a post and horsewhip her.”

Obviously, had bystanders attempted even a relatively mild form of on-the-spot “discipline,” it would’ve been blasted all over media as demonstrative of “racism.” We all know it’s not, but it wouldn’t matter. Ironically, the fact that nobody even attempted to stop her is a sure sign America’s problem isn’t racism. When a person, especially a Black person, can behave like that and walk away unscathed, it obliterates the pseudo-religious belief that White supremacy still exists in this country.

Where am I going with this? As a practical person, my first concern is maintaining social order. Maintaining social order requires the exercise of violence. There’s a debate raging on X at the moment over the movie Starship Troopers concerning its effectiveness as form of satire. As much as I enjoyed the film, the entire debate is silly, because the film failed to capture the source novel’s message, as outlined by author Robert Heinlein.

That message? Civilization is established and maintained through violence. Either we, the civilized, employ violence in disciplined fashion to maintain order, or the savages, like the woman in the video, will use violence barbarically to court disorder. Someone who doesn’t understand this (not saying that’s you, Brian) has no business being a citizen, no business taking part in the political process. I believe this in my heart of hearts and has been a constant element of my platform here on this blog.

Finally, reader “Spottswood” writes:

“US power overseas is waning” - Are you sure about that? How did US power look during Carter post-Vietnam, or in the early 90s with the Somalia humiliation. Pre-9/11 there was more talk of US decline. In recent years, the US power has utterly humiliated Russia militarily, at a total discount, without spending a drop of its own blood. Xi Jinping’s reign is ruining China, with a few nudges from DC, and now ending talk of the “China Century.” Sunni terrorism is quiet. The US can do whatever it wants to Iran and its proxies who are more of a nuisance than anything. These are the hard power realities without even touching on how America has swallowed all other soft power - cultural/philosophical rivals. If this is your idea of decline, what does utter dominance look like?

This is a fair point, but I still disagree. Superpowerdom isn’t when bad things don’t happen to a country - after all, 9/11 occurred when the U.S. was near the peak of its power. Superpowerdom is when bad things can happen to you, but the country manages to carry on with business as usual.

Obviously, the U.S. didn’t carry on with business as usual after 9/11. When the history of America’s collapse is written, many will undoubtedly argue that the beginning of the end was 9/11. So maybe that’s not the best example. But what about Somalia, as Spottswood notes?

For his argument to have merit, the U.S. would’ve had to become less interventionist following the October 3, 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, immortalized in the book and movie Black Hawk Down. But that’s not what happened. If anything, the U.S. became even more interventionist. After departing Somalia in 1994, the U.S. intervened in Haiti later that same year. It spent almost the whole decade in the Balkans and, since 1991, never left Iraq. As important, no challenger to the U.S. existed at the time. Russia was teetering on the brink throughout the ‘90s and China was still building its way up to becoming the global power it is today.

Superpowerdom is about making mistakes, having your adventures result in failure, and still doing the same thing over and over again without paying a price for it. Eventually, the bill does come due. But until the bartender cuts us off and closes us out, we can keep racking up the tab.

The U.S. is in no position to carry out its foreign policy from the ‘90s or even the 2010s. As for Russia, the fact that it invaded Ukraine was a major blow to U.S. preeminence, a fact which still escapes many. These sorts of things aren’t supposed to happen when America is in charge, but not only did it happen, Ukraine is likely to lose the war. And while invading Taiwan is likely to be a bad move for China, the U.S. is likely not going to be able to stop it from happening, either. Any victory from here on out will come at a hugely disproportionate cost for relatively little gain.

Whatever comes to pass, the U.S. will emerge weaker, not stronger, when it’s all said and done. There simply isn’t a crown lying in the gutter the way there was at the end of World War II. If anything, the crown will fall off America’s head and end up in the sewer, to be washed out into the ocean.

Plenty Of Fodder For Conversation

That’s all we have time for now. What are your thoughts on anything we discussed? Do you think other, less-developed countries have the fundamentals of civilization-building down better than the U.S.? What have you seen in your travels? What was your reaction to Taylor Twellman’s statement? Did you find it as hypocritical as I did? Finally, are people like me being a squish when it comes to immigration?

Do your thing in the comments section.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

What about self-deportation to solve the immigration problem? Lock down the border, remove birthright citizenship and end all entitlements for non-citizens. Make it so painful to be here that they leave on their own with massive penalties to those who help them stay. I’d even be open to offering a travel stipend to return home for those who willingly turn themselves in.

Taking a look at the Wikipedia article, it seems that only 750 Border Patrol officers were assigned to Operation Wetback in the 1950s and about 1 million were deported or left. So it’s not necessarily the case that such vast numbers of officials are required to make an impact.

I have always been struck by the expectation of all parties that a a refugee claimant who just shows up is automatically entitled to free accommodation, food, etc. What if they just weren’t given these things and most were subject to immediate deportation? I do think that Western societies are getting to the point that it’s just not possible to do these things for these migrants and the limits will be hit. At that point the political consensus will have to change in some way.