Our good friend Fabian Ommar is back, this time with an essay on how to deal with the consequences of President Donald Trump’s aggressive tariffs against the world. We’re in for a rough ride, whether you like it or not, so it’s best to learn from someone who’s lived it, lived in an economy where strong tariffs were in place, and knows what life is like under such an economic regime.

It’s easy to get mad about this or that policy. But before losing our minds, let’s first ask ourselves: why does it make me angry? Or should I even be?

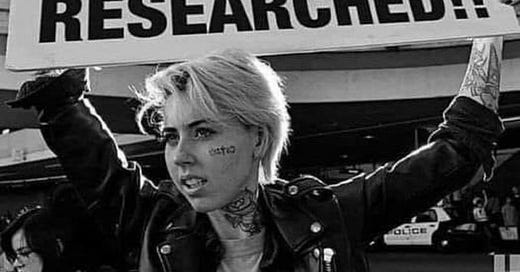

Everyone Wants Reform, Until It’s Time To Reform

Before we begin, I want to share some thoughts about Trump’s tariffs plan. I understand why everyone thinks it’s a bad idea. It probably is. I doubt anyone’s going to miss the Trump days 20 years from now any more than Russians miss the days of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin.

Here’s the thing: reform never comes easily or painlessly. All my life, people, especially on the Left, have been asking, downright begging, for economic reform. To make it more beneficial for Americans, for Average Joe, for Main Street, not Wall Street. Our universities don’t promote capitalism; they promote greater government intervention in economics, in some cases, outright socialism. There are entire courses and textbooks devoted to critically attacking free trade and neoliberalism.

Well, here we are - we have a president engaging in the most radical economic reforms we’ve seen in generations, breaking down that very free trade, neoliberal model our economy has lived off of for generations. Now all of a sudden, everyone thinks free trade and neoliberalism are good ideas?

You can argue that Trump’s specific plan is flawed, and that there are better options. Fine - what are they? I haven’t heard anyone offer any alternatives beyond maintaining the status quo or taxing the rich. If there are alternatives, I’d love to hear about them, in as simplified a form as possible. Don’t just throw numbers at me. I may come off as an intellectual at times, but I’m a simpleton, at the end of the day. We all are. We have to be, otherwise, we’re wracked by indecision.

The fact is, nobody knows how to fix the economy. Nobody knows how to fix any of this. That includes Trump. That might make what he’s doing imprudent and reckless, but again: what’s the alternative? Revert to the status quo and keep kicking the can down the road, like we’ve been doing all this time? Does anyone really believe that road will never run out in our lifetimes? That, 20 years from now, we’re not still going to be having the same asinine conversations about how to make the economy work for the average American?

About tariffs themselves: they’re neither good nor bad. Like most things in life, tariffs are value-neutral. It depends on how they’re employed and when. It’s not like we’ve been living without tariffs this entire time; they’re not some economic nuclear bomb nobody’s ever employed. As with anything else in life, there’s no use getting angry about a topic you don’t know much about. We’re not talking about being forced to pretend like gender is fluid or something like that.

Anyway, I’m not writing this so we can have a policy debate. That’s not what this essay will be about. But it’s something to ponder upon - if we don’t take action now, then when? And what will we do?

I’m still dumbfounded by the sheer immaturity of this tweet by geopolitical “expert” Ian Bremmer, clearly written in a fit of anger:

americans are the shortest term folks imaginable. the idea that we’ll happily accept short term pain for something—anything—long term flies in the face of our national experience.

It’s literally what separates adults from children: suffer now, prosper later. It’s one of the big lessons we learn in our transition to adulthood. I don’t know if what Trump is doing is going to yield success in the end, but I do know this: if hard times are coming, and they are, I’d rather make the necessary sacrifices sooner rather than later, when it might be too late for us to do anything about it.

I realize not everyone feels this way. Just don’t pretend like refusing to endure hardship now so we may all benefit in the future is a virtue. It’s pretty obvious the elites don’t just have a different worldview; they live by an entirely different set of values.

The Experts Are Correct (Unless They Disagree With You)

It’s happening again: in an attempt to explain why Trump’s policies are bad, we’re calling in the Expert Class once more to tell us why. Since they’re experts, the clergymen and shamans of our time, their word is gospel and never to be questioned.

Unless they say something that goes against popular opinion, of course. The reality is, most of us don’t understand economics and finance as well as we think we do. So much of the discourse is driven by grievance, a belief that someone is gaining at the expense of another (zero-sum thinking). This isn’t entirely false, but it’s certainly not entirely true, either.

Economic populism is, well, popular, because most people don’t understand how prices are set. It’s hard to make these points without sounding like an intellectual snob, and Britain’s prevailing culture is highly anti-intellectual, but economics has the combination of being both counter-intuitive much of the time and quite boring most of the time.

During the worst of the inflationary wave during the Biden administration - “Bidenflation,” as it was called - leftists accused energy companies and grocery store chains for price-gouging, going as far as to call for price controls. The experts would’ve disagreed with these people. Nobody would want to listen to experts explain why we have no choice but to pay higher prices, right?

In fact, there’s something of an inverse correlation between the popularity of a policy and its efficacy:

Rent controls are much loved by the public – the idea attracts large majority support in polling, because no one likes greedy landlords. Only 2 per cent of economists support the idea, because rent controls tend to discourage supply. People also tend to blame wealthy foreigners for buying up property and leaving them empty, even though this plays almost no part in the housing crisis.

Of course, some things are zero-sum, housing included: there are by definition a limited numbers of properties in desirable areas, and it is also politically difficult to build more. If your contemporaries all become rich and spend it on an inflationary housing market, then you do lose out - unless you can persuade NIMBYs to allow more development. But then, most people hate ‘luxury flats’, and don’t understand that the more luxury flats that are built, the more that houses are affordable to everyone.

Ed West is British - in America, rent control is also publicly popular, though this popularity is nuanced. The point is that expert opinion, right or wrong, isn’t intended to validate public sentiment. It can be exploited in such a manner, yes, but expert opinion is meant to establish a factual basis for public policy formation. Again, it doesn’t work out that way in practice, but that’s its intended purpose.

It’s easy to defer to expert opinion when they say something you agree with. When they say something you disagree with, be it on rent control, minimum wage, or whatever, the experts are standing in the way. The reality is, everyone looks to the experts with confirmation bias, not out of any real desire to learn the facts.

This doesn’t mean the experts are wrong. But it’s important to be honest with ourselves on why we seek out expert opinion, and remember that the same people pointing to expert opinion on tariffs will just as easily dismiss it when they hear something they didn’t want to hear about another topic.

Economic Reform Is Never Easy

Let’s get to Fabian Ommar and his read on the situation. Here are the stakes:

Everything is attached to the economy, and today, it runs on globalized trading more than ever. The majority of products we consume daily are “global” in one way or another.

That arrangement is about to face profound changes and suffer large shocks, bringing instability to levels not seen during the last three or four decades.

Markets already provided a glimpse: shortly after the announcement, the DOW crashed more than 1,500 points, the S&P dropped 4%, and the NASDAQ dropped another 5%. Trillions vanished in a matter of hours. The Russell 2000 index dropped 20%, indicating a recession on the horizon.

At the moment, those are just numbers on a screen.

However, once they materialize in the real world, the industry and commerce, the market, the government, and the population will start feeling the impact. And it will be painful.

Stagflation, poverty, layoffs and rising unemployment, austerity, even larger wealth gaps, and everything that comes with that—social unrest (riots, violence, crime, strikes), shortages and disruptions, possibly market crashes and bank runs.

In short, this is a very 1980s-like scenario.

The 1980s were an economically tumultuous decade. Just ask your parents - the U.S. underwent the worst recession since the Great Depression before the Great Recession of the 2000s, with things more unpleasant throughout the rest of the world. If you want to look at the glass as half full, note that things didn’t come crashing down in the 1980s, and many of those who lived through the decade as a wonderful time. However, the 1980s were also 35 years ago. Memories have faded or were replaced with happier ones.

Ommar goes on to explain how tariffs are actually supposed to be implemented.

Tariffs and deals are deliberately studied, negotiated between nations, and implemented in phases to avoid significant disruptions and panic.

That’s how these things run during normal times, but these are not normal times. And even though we cannot see the bigger picture yet (perhaps ever), from a distance, it feels as if the tariff deal was purposely crafted to cause the opposite effect, which it did.

My own read of the situation is that Trump is engaging in economic “shock therapy.” Basically, he’s trying to force through reforms which would normally take months, even years, to implement without causing considerable discomfort. The reason I keep comparing Trump to Russia’s Yeltsin is because that’s what the Russian Federation’s first president did - force through all sorts of reforms, including privatization (generally considered to have strengthened the power of the post-communist oligarchs), in an all-out gamble to transition the country away from communism and towards capitalism.

The reality is that Yeltsin did exactly what needed to be done, but nobody thanks him for it, because it caused tremendous hardship for Russians in the 1990s. Our friend

has been talking a lot about that lately - check out his Substack to see what he’s been saying.That said, if anyone’s surprised Trump is doing this, they simply don’t know Trump as well as they think they do, nor did they take him seriously, difficult as it may be to do at times:

Be that as it may, Trump and his administration have been hinting at this since before the election, so it shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone paying attention. The world won’t end, but it certainly won’t return to how it was before the 1990s.

On that last point, Ommar is saying, I think, that we’re headed for a long-term period of economic regression. Though the 1980s were a difficult time economically for most of the world, it was still overall a period of growth. A lot of countries made their gains during this time. To invoke Russia again, the world, the West especially, is looking at years, maybe decades, of economic stagnation, if not outright decline. It would’ve happened eventually, no doubt, but Trump’s policies, if we are to ascribe any logic to them, is to suffer now as to not suffer later.

Why Won’t Americans Work In Factories?

This is arguably Ommar’s most controversial argument:

Let’s be honest: does anyone think Americans will work 10-hour shifts at a U.S. Nike or Apple factory for $5 an hour? Or Canadians, or even Mexicans? That’s what Chinese and Vietnamese workers do.

He’s not wrong, of course. But if we’re going to agree with this statement, let’s be honest with ourselves about why we ended up here. We’re here because three successive generations - X, Millennial, and Zoomer - were funneled towards four-year universities, bachelor’s degrees or better, and employment in the professions.

It sounds like a great idea, until you learn about something called “elite overproduction.” Read the writings of Peter Turchin if you want to learn more, but at its simplest, it means, the economy cannot support a society comprised of a majority of them. The very nature of elites means there will always be fewer of them than those of lower classes. This means many of the elite-aspirants will end up doing something other than what their high-priced degrees were intended to provide access to. But factory work isn’t one of them. Not only are there not many factories, it’s just not what entire generations were raised to do.

You can’t raise entire generations on one set of expectations for life and then suddenly expect them to settle for something else entirely. People need to be adaptable, but some transitions are difficult to make. Remember: de-industrialization in the U.S. began in the 1970s. We shifted away from factory work as a career option long ago.

So, no, Americans won’t do these jobs. But let’s at least be honest about why they won’t. It’s all about what you tell Americans what to expect out of themselves and out of life.

Ommar says we shouldn’t expect America to re-industrialize and while the economy needs fixing, what replaces the service-based economy won’t be what came before it:

The truth is that the re-industrialization of the U.S. has other obstacles against which tariffs and protectionism are ineffective and could, in fact, turn the problem much worse as it did in my country for decades before it opened to the world in 1991 (more on that in a moment).

Globalization will be replaced by something different, something new. I have no idea what, and as interesting and exciting as this topic may be (it is), I’m more interested in staying prepared for whatever happens until we get there.

Even if, somehow, manufacturing could be brought back to the U.S., these aren’t your grandfather’s factories - today’s factories utilize far more automation, meaning the people who work there are going to be fewer in number, primarily operators and maintainers of complex, high-tech systems, not fabricators of the final product. This means today’s factory workers need to be highly educated and skilled, and aren’t the kinds of positions you can recruit for right out of high school. This is just realism - we’re not going back to the days of Bethlehem Steel and General Motors spitting out Pontiacs in Detroit.

Protectionism: Theory Vs. Practice

Ommar speaks on his country’s own experience with protectionism:

As I mentioned in a recent post recounting Brazil’s 1990 Confiscation, President Collor’s biggest achievement was opening the country to the global market. Up to that point, importing was incredibly bureaucratic and expensive for companies and businesses, and outright prohibited for citizens in general.

Consumers had limited choices; a lot of stuff wasn’t even available to us. Shortages were commonplace. Things weren’t as bad as in the USSR and other communist countries, but also far from the reality of free markets such as the U.S., Canada, Japan, and most of Europe.

But perhaps worse is the fact that rather than strengthen and develop the national industry, protectionism turned it obsolete, archaic, unproductive, and accommodated. Even now, 30 or 40 years later, productivity is low, and many sectors are still trying to catch up to global competitors.

That’s what happens when tariff wars and trading protectionism kick in and globalization gets reversed.

What he’s talking about is theory versus practice. Not all good ideas in theory pan out in reality. A lot of Latin American countries besides Brazil experienced economic booms in the 1980s and 1990s, like Chile and Peru. But this was primarily due to adopting free trade and neoliberal policies, not protectionist ones. In fact, these same countries were often criticized for doing so, the lingering inequality in these countries being cited as arguments against such policies.

Like I said before, however, the critics have no clue what they really want. The rest of us sober-minded individuals need to be able to look at things from both sides. Free trade and neoliberalism isn’t all good, and millions of Americans have missed out on the benefits of such an economic arrangement. But protectionism often hurts everyone in the long run. It’s sort of like socialism, at least in its effects.

Protectionist policies could bring some benefits. But those benefits are likely to be quite limited and it may be a long time before the pay-offs get here. The lesson seems to be that protectionism and tariffs are things worth applying in small, timely doses, but cannot be used to bring about wholesale positive economic changes, not without considerable hardship, anyway.

The bottom line is this:

We should prepare for that, but in this environment, navigating inflation and deflation becomes a tricky proposition: some things will rise, others will fall. The market will become a roller coaster, but assets can also oscillate, with rare exceptions.

It was like that in my country and many others (Argentina, the U.K., etc.) until the mid-1990s, and it takes a rather clear and calm mind to make sound financial decisions in such a volatile environment.

A different mentality and mindset are required because some moments and events will demand quick thinking and fast action, while others require restraint and patience.

Recessions aside, Americans have been blessed with an economic environment which has been more stable than not. That’s about to change. At least, the amount of time between upturns and downturns is going to shorten and the upturns won’t be as resounding as they used to be. In other words, America’s economy is going to start looking and feeling like that of other countries.

What’s the future looking like? Are we going to become like Britain, which has been dealing with double-digit inflation for years on end? Are we going to look like 1990s Russia, which basically suffered its own Great Depression, with its economy not being robust to begin with?

Money On Your Mind

All I know is this: we need to be prepared, so let’s talk about that. Ommar offers his suggestions; make sure you read his essay in its entirety, but I think these three recommendations are worth sharing here:

– Financial preparedness is critical. Myself and others keep repeating that for a reason. During a round table with European preppers late last year, I mentioned that I’m still doing my street survival training, though not as much because I feel that dedicating myself to finance and preparing my household for a prolonged crisis is now more urgent.

– Adaptation beats preparation. Selco addresses this in his latest post about the fluidity of SHTF. There’s no way to tell how long a crisis will last, or how severe it will be, so being flexible and adaptable is more important than having a massive stockpile of everything.

– Another critical skill for surviving economic crises is the capacity to tell signal from noise, the ability to sift through the multitude of information and data coming our way all the time. Choose your sources wisely, but maintain critical thinking at all times. Remember, the media has a history of being far less than honest and unbiased.

There’s no excuse for not being financially prepared. None. It’s part of what it means to be an adult, to be independent. It’s not just about having enough money to cover your expenses, it’s also about learning to prioritize. On the topic of prioritization, when it comes to being prepped, not only should you ready yourself for the most likely emergencies you expect to encounter, you should also be preparing for emergencies which appear most imminent, like a financial crisis. It might be more interesting to do so, but learning how to survive in the wilderness is probably not the best use of your money and time at the moment.

Making it through life without losing your sanity in the process involves being flexible. It doesn’t mean you always change things around, but you need to be willing to shift gears to accommodate reality. For example, if it’s hot outside, you need to figure out a way to stay as cool as possible, hydrated, or inside as much as possible, because the heat will always win. Complaining about the heat won’t do a thing. Money is the same thing. Nobody likes inflation, but at some point, we need to adjust our lives to the fact that prices are what they are.

I look at social media more positively than most, but it’s just the truth that it amplifies the voices of those who shouldn’t have an audience. That doesn’t mean we can’t be discerning, however. The reality is, a lot of people are angry about the tariffs just because Trump is the one behind them. A lot of these same folks couldn’t care less that prices were going up during the Biden years, or that thousands of businesses across the country had to close since 2020 due to the lingering impact of both inflation and the economic shutdown justified on the grounds of COVID.

Always pick quality sources. Financial experts like Lyn Alden are a good source of information and reason during these times. Finding people who can speak dispassionately about an issue is one way to stay sane during difficult times.

Daisy Luther, the brains behind The Organic Prepper, said her own piece on how to prepare for the trade wars. It turns out we do, in fact, have recent experience to draw upon:

The obvious way this affects us is that we will face higher prices for what’s available, and fewer choices will be available. If the prices are so outrageous that vendors like Amazon, Target, and WalMart are not making purchases, we’re going to be looking at some very limited store shelves in the not-so-distant future.

Think back to the days of Covid, when cargo ships were halted and our store shelves were greatly depleted. We faced store limits on things like toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and eggs, if you could even get these things at all. It was partly panic-driven – shoppers cleared out the stores in one crazy weekend. But after that, it took a long time for our shelves to become full again as the supply chain shuddered under the weight of the changes. Do you remember also the microchip miniapocalypse we faced during that time?

Basically, what we’re preparing for is 2020 without a pandemic, without the lockdowns. See? Things aren’t all bad. I’m being sarcastic there, but you all know by now I’m a glass half-full kind of guy. 2020 wasn’t a good time for any of us, so if the worst is that we get the economic problems of that year without the rest of it, oh well, you’ve got take what life gives you.

Luther goes into a lot more specifics about what kinds of goods you can expect will become more expensive or limited in availability. Again, we all went through that five *gulp* years ago. The mental framework for living through economic hard times is there, we just need to let it surface again.

Like Ommar, Luther stresses the importance of keeping your head on straight. I love what she has to say here:

Most importantly, remember that the things that truly matter most don’t come from China.

Remember: most people of the world live in a state of some form of deprivation. In Europe, many go without bathing daily, due to the cost of water and the unavailability of heated water. It’s not that Americans deserve to, but it’s just a fact we’re now approaching a time where we’ll need to learn to live with less.

We Wanted Change. We’re Getting It.

Before we close it out, some final thoughts. I want to reiterate: my whole damn life, I’ve been hearing about how the economy needs to be reformed. In college, I never heard anyone make a case in favor of free trade or neoliberal economics. All I heard was how exploitative free trade and neoliberalism were, how our economy not only leads to terribly unequal outcomes, but does so by design.

Yet, as Trump attempts reform, I hear nothing from the critics except “tax the rich.” It’s an idea so unhelpful that it’s not worth refuting, except to say our problems go far beyond the government not getting enough of our money. Nobody has made the case for why giving the government more money is going to make us more prosperous, either. That’s because it’s not a serious idea. It’s just another one borne of grievance. You’ll find very few financial experts who suggest raising taxes to create greater prosperity.

Finally, never forget: no matter the wonders of the economic status quo pre-Trump, millions of Americans have never enjoyed its purported benefits, besides low prices, maybe. You’re not going to sell people on something they not only never had, but never will. At no point in my life did I ever hear anyone express satisfaction over the cost of living, health care, housing, you name it. Finally, everyone talks about how we need to help poor people, to give all Americans a chance at prosperity. If it wasn’t happening before, and helping poor people is so important, why argue against reform?

Bottom line: if you want change, don’t argue in favor of the status quo.

What do you think? Will Trump’s tariffs bring any sort of benefit? Or has he placed the economy on a collision course with ruin? What are your suggestions for enduring the coming financial hard times?

Let’s talk about it in the comments.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

If you want a serious criticism of neoliberal free trade theory, I recommend Ian Fletcher's book Free Trade Doesn't Work. An even more academic analysis is Gomory and Baumol's Global Trade and Conflicting National Interests.

I doubt any of them would approve of Trump's economic behavior last week. But both make the case for limited protectionism. In fact, Trump's 10% global tariff is exactly what Ian recommends.

It comes down to the simple reality most people need to stfu. One difference between America and other countries, our market is so huge that we can employ more people supporting it.