The High Cost Of A Low-Trust Society

“You’re low trust, you have a weak culture, so what do you want me to say?”

Did you have a nice Halloween? These people sure did:

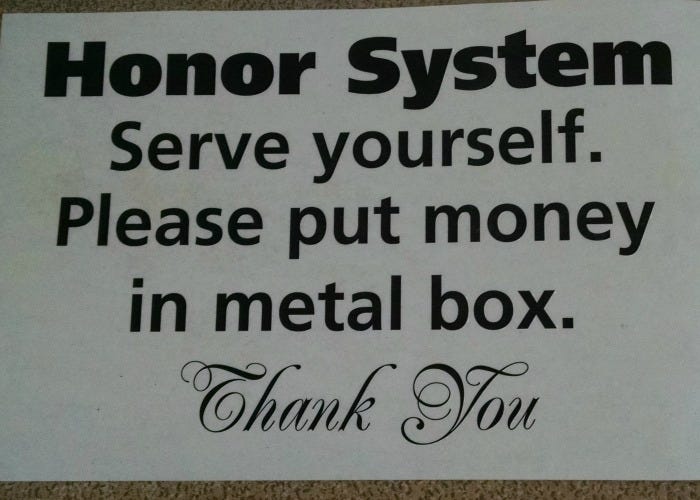

Here’s a link to the whole video. It’s trick-or-treaters, accompanied by their parents, emptying an entire candy bowl for themselves. This despite the fact the residents had put up a sign asking visitors to only take one piece of candy:

You may notice that the visitors are speaking a foreign language, possibly Spanish. It’s possible they didn’t understand what the sign said. I don’t think that makes a whole lot of difference. Emptying an entire candy bowl, knowing there’s going to be other trick-or-treaters, is bad manners, no matter what language you speak.

The video has kicked off a debate online, with people regarding it as an example of why trust is declining in the United States. The resident implemented the honor system and it completely collapsed with one group of visitors. This in what seems to be a nice neighborhood. Some have noted this group may not live in the neighborhood, but again, that doesn’t matter. The fact they showed up at all means there isn’t any escaping the decline of trust in the country.

Why am I talking about this? What does this have to do with internal conflict, civil war, prepping, personal safety, or any of the other topics I regularly talk about?

You already know that I believe our society has entered a terminal decline and that it’s irreversible at this point. My “job,” if I have one, is to prepare you for it. One of the things you need to expect during the decline is the loss of trust in society. It’s a defining characteristic of a society, dictating what life is like in a given place.

First, what does it mean to be “high-trust” and “low-trust?” The simplest answer is that a high-trust society possesses shared ethical values, whereas a low-trust society doesn’t. The irony is that low-trust societies tend to be familial and kinship based, yet they require excessive amounts of governance and regulation for it to function. High-trust societies require less enforcement from formal, institutionalized authority, but can still be advanced and high-performing because the relative internal tranquility leads to large-scale empowerment and a greater focus on solving problems and delivering results, rather than resolving conflicts between members of society.

So, what’s the state of trust in America? The answer may or may not surprise you.

From Our World in Data’s study of trust:

The darker the shade of green, the more the trust a society has. I have to say I’m both surprised and not surprised by these numbers. I wasn’t too surprised by the U.S.: 39.7% of Americans believe most people can be trusted, which is higher than I expected, but also consistent with what I’ve witnessed spending my entire life in this country. Americans generally want to trust other people, even if they honestly don’t in their heart of hearts. Despite our reputation, Americans are well-meaning people.

What surprised me was how low social trust is in places like Japan and South Korea. These countries are regarded as high-trust and cohesive and are ethno-states, yet they scored lower than the U.S., while still being in the same statistical neighborhood. Perhaps the reason Japan and South Korea seem less dysfunctional isn’t a matter of trust, but a matter of something else entirely. It’s possible for societies to have strong cultural norms while lacking trust, with the norms regulating the distrust people have for one another.

Not surprisingly, the continental European countries of Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, along with the Nordic countries (especially) rank the highest. Based on available data, high trust is, unsurprisingly, less common throughout the world. It seems to be something of an Anglo, Germanic, Nordic, and Chinese phenomenon, an observation certain to spark spirited debate. Meanwhile, places like Latin America have notoriously low levels of social trust. Even in bona-fide nation-states, trust is quite low, lower than the U.S. Most notorious is France, while Eastern European countries like Hungary, Poland, and Russia are low-trust despite appearing fervently nationalistic, if only from the outside.

There’s a lot you can talk about when it comes to the topic of trust. I want to share one more chart before getting to the point:

Two things are true at once: trust in America has fallen precipitously in the last 50 years, yet it’s also remained more or less consistent for the past 30 years. What’s going on here is a tale for another time and place, but I find it interesting that despite everything that’s happened the last several years, Americans don’t seem to have lost any more faith in one another, even as their overall faith in one another remains low. It’s a strange dynamic, but it’s observable.

Why does trust matter? The answer isn’t as self-evident as it may seem. As stated above, even relatively lower-trust societies like Japan and South Korea have functioning societies and advanced economies. The problem goes back to how low-trust societies require extensive amounts of governance and regulation in order to function. Japan and South Korea have strong cultures which perform the task of managing differences between individuals. Culture has a much simpler approach to managing human relations, but it’s also more blunt. Whereas a bureaucracy might attempt to hear both sides and generate a lot of paperwork in the process, a culture basically picks winners and losers in advance, based on what shared morality and ethical values dictate. In that sense, a strong culture is as good as high-trust.

But the U.S. lacks a strong culture, too. One way you can tell if a society has a strong culture is whether everyday people like you and I are empowered to enforce social norms. Everyone know what I’m talking about because I’ve made this point time and again in this forum - every social interaction in America carries with it an increased risk of intractable conflict and violence. By “intractable,” I mean that people cannot resolve problems without it turning into a shouting match. Millions of social interactions between strangers take place daily without something bad happening, yet it’s also true that social interactions have become far less predictable. How well people in a given society resolve conflict is where the rubber meets the road. If people get the sense that asking someone to move their car will elicit nasty looks, unpleasant attitudes, or even threaten their safety, people will come to avoid social interactions with strangers entirely, thereby unraveling the social fabric.

To channel my inner Simon Cowell, “You’re low trust, you have a weak culture, so what do you want me to say?” Since we bear witness to America’s weak culture daily, the next step is to establish what a truly low-trust society entails. This video provides an example in Greece. You don’t need to watch the entire video (though you should), just watch the section titled “What is a Low trust society?”

That’s all pretty interesting, especially the part about how low trust exhibits itself in home construction. When I visited Colombia earlier this year, I heard the same thing regarding courtyards - they’re intended to conceal what’s inside the home. I always thought courtyards were a sign of wealth.

This brings us to an interesting point - we often hear about the “Latin-Americanization” of the U.S. The term is regarded as a pejorative, but facts don’t lie - corruption, crime, inequality, and poverty are rampant in Latin America. But it’s not exactly the Third World, either, so it’s logical to assume that if America does collapse, our southern neighbors are a good example of what we’ll mutate into, especially when you consider demographics. No matter what people like to think, people bring their cultures with them and stronger cultures will always overwhelm the weaker cultures. I think you’re seeing that unfold in real time in the wake of the Israel-Gaza conflict. Our institutions have utterly failed to stem the tide of anti-Western and antisemitic sentiments and now we have no answer for it whatsoever. But I digress.

The more America declines in trust, the worse corruption, crime, inequality, and poverty are likely to become. It may not happen overnight, though it’ll certainly accelerate at times. Low-trust societies often compensate for the degraded state of interpersonal relations through big government and sprawling bureaucracies intended to “officiate” human interactions, but I think we’ve also exceeded the point of diminishing returns on that. There are just too many people out there and bureaucracies are unwieldy, inflexible things.

As has become a constant thread throughout my writing, the state regards all of us as equal in the most literal sense. None of us are ever right or wrong, “aggressor” and “victim” roles are constantly changing on a minute-by-minute basis, or at worst, some people will always be regarded as the aggressor and others as always the victim according to the prevailing political climate. Either way, there’s no real “appeal” system because we have no ethical values in common. Nor does this system provide any sort of pathway to resolving interpersonal disputes beyond “call the authorities.”

Corruption exists in America and throughout the West more broadly. However, our brand of corruption differs from that of the developing and undeveloped worlds. It possesses a veneer of legality, often a matter of people exploiting loopholes or doing what they think the law permits them to get away with, only to find out it doesn’t. You don’t see the blatant flouting of the laws as you see in most of the world.

Could that be changing? The following example is from the United Kingdom, but I think this sort of thing could find its way across the Atlantic:

The last tweet is what really caught my attention - the disparity between the scale of government regulation and the government’s ability to enforce those regulations. Simply put, it’s suggesting that “hard” corruption is inevitable even in places like the UK and, by extension, the U.S., because when you make the managerial state so big as to become unwieldy, the only way for the system to work is through corruption. When you have too many rules and regulations, but can’t opt out of the system, either, you inevitably begin picking and choosing which rules and regulations to follow, inevitably resulting in corruption. You can’t undo this without bringing the entire system to a crashing halt, which is simply not an option.

This is all about more than just Halloween candy. But the Halloween candy example is illustrative of how a low-trust environment hurts us even at a personal level. Imagine needing to constantly be on guard, to view everyone as a potential thief or a competitor, being unable to rely on the kindness of strangers, and so on. On some level, we’re already there, but I think most Americans prefer to at least pretend we can trust others. The fact that our sentiments have remained stable for so long suggests as much, though it ought to be remembered there are hundreds of millions of people in the U.S. - social attitudes tend to change slowly in bigger, more diverse populations. But if crime continues worsening, if people continue to lose faith in our institutions, if America collapses as a superpower (as I believe it will), people’s behaviors will change, even if our sentiments don’t, at least not right away.

Not convinced? Look at what businesses are doing in the face of rampant theft. How many of you thought this would become a thing? It certainly never crossed my mind:

Imagine our trust descends to the level of Latin America or even France. And there’s no strong culture to serve as a bulwark against further social breakdown. We’d definitely end up in uncharted territory. The only way to maintain social order then would be through truly strong governance and I’m not talking about putting more laws and regulations on the books. I’m talking about violence.

Consider Singapore:

Singapore is a low-trust society, with numbers close to that of the U.S. Yet a person feels perfectly safe leaving a $15,000 bike unattended and unsecured! How could this be? Singapore has a strong culture of lawfulness because the state so harshly enforces the rule of law. In America, we think punishing theft is unbecoming because “it’s just property,” but a safe society cannot be administered without harsh consequences. Either the people administer the consequences or the state does. Pick one - “neither” isn’t an answer.

If you don’t like the state enforcing social order, consider what it means for the people to do so. Consider the incident from New York City the other day which went viral, where men confronted someone tearing down flyers with the names and faces of hostages being held by Hamas in Gaza. I suggest you watch this video - there’s no graphic content aside from harsh language and it’s a perfect example of people enforcing social order:

John Daniel Davidson discussed the implications of the incident in The Federalist [bold mine]:

One of the men gets in the Arab guy’s face. “This is New York City,” he says. “You don’t have a f-ckin’ right to touch that sh-t. This is a free country. You can wave your Palestine flag and say ‘death to the Jews’ or ‘America’ or whatever you want. But we can put up f-ckin’ signs.”

He tells the Arab guy to shut up and move on. He tells him some other things too, like that he’s going to litter the floor with him, that he’s dying to put him in the hospital. The Arab guy shuts up and moves on.

The clip went viral for how much it contrasted with the videos we saw all last week, of pro-Hamas college students self-righteously ripping down posters of missing and kidnapped Israeli children. In nearly every video, the person holding the camera tries to shame the Hamas supporters, plead with them, or persuade them that what they’re doing is wrong, offensive, and morally insane. All to no effect.

Not this anonymous blue-collar man in New York. He understands there’s no point shaming or pleading with such people, so he instead brings something to the table that’s been missing from these exchanges: a credible threat of violence. He understands the time for pleading or persuading has passed, and that people who rip down posters of missing Israeli children deserve no toleration, no dialogue. They must be stopped — by force if necessary.

You may bristle at the thought of violence, but all societies are established through violence and maintained by the threat of it. It’s a matter of who’s doing it and why. In many ways, the NYC incident is indicative of what America’s been and what it’ll take to keep it together, short of authoritarian governance, which none of want. But it depends on a willingness of a large number of people to put skin in the game and confront the barbarians and savages, along with those who enable them, and speak in solidarity against the forces of national disintegration.

You need a strong culture for that.

It seems as though I’m concluding this post with more questions than answers. For example, this is very much a “chicken-or-the-egg” riddle: are disorder and instability what’s causing the decline in trust, or is a decline in trust what’s causing disorder and instability? I don’t think the answer is as obvious as it seems, as we’ve clearly been a low-trust society long before Trump, COVID, or today’s events.

Another question to consider: do we even want a high-trust society? Sure, we like living in harmony with our neighbors, not having all these laws and regulations, and operating by the honor system. But as the example of Sweden demonstrates, high-trust societies are susceptible to subversion and being displaced by stronger cultures. Just as there’s a high cost to low trust, there may be a high cost to high trust, also.

Unless, again, they’re accompanied by a strong culture. Personally, I’ll take the stronger culture over higher trust. The former seems more durable than the latter and humans are, ultimately, untrustworthy, anyway. Ultimately, we trust those closest to us more than those further away from us, even as those closest to us are capable of hurting us the most.

High-trust societies work best when underpinned by a credible threat of violence and only a strong culture can produce that, as the NYC example proved. If you set up a candy bowl on Halloween and have a way of shaming and punishing those who get greedy and take more than they’re asked to take, you deter them from breaking the rules. Violence isn’t always about throwing punches - it’s about making people pay a price, even if it means only losing face and your standing in society. Certainly, the worse the transgression, the higher the price becomes. But you have to make people pay a price for abusing the kindness and generosity of others in order to maintain a high-trust environment.

Much of this is theoretical and beyond our capability as preppers to redress. We’re not here to solve society’s problems, we’re here to survive them and create safe harbors from the storm. Maybe one day, hopefully sooner rather than later, an opportunity will arise where we can establish a new social order, built on a strong culture, where we can all trust each other once again and run more of our society on the honor system.

Until that day comes, secure your integrity, act with integrity, and instill integrity into those closest to you. You’re not going to get any kind of example from our leaders.

What are your thoughts? Does the data on trust throughout the world surprise you? Do you think America’s a low-trust society? What are some examples in your life of high-trust and low-trust behavior? Let’s discuss in the comments below.

UPDATE: Reader “Kyle” says:

I stumbled across your page via Rod Dreher’s substack and have pored over at least a dozen of your articles. I want to commend you for your persuasive writing about crime and human nature, it’s really got me thinking…

First, thank you,

for what you do for me personally and what you do for all of us. If you don’t know who Mr. Dreher is, you’re missing out on arguably the play-by-play commentator of America’s decline. He runs a subscription-only blog, but he also has a free column at The European Conservative.Kyle continues:

I feel pretty comfortable assuming that the family stealing candy isn’t from the neighborhood. In my experience, it’s common knowledge that the ritziest neighborhoods have the best Halloween treats, so lots of teens and/or working class families make trips into the “nice” side of town in order to indulge in some fantastic candy. (At least, that’s what happens in my folks’ neighborhood in suburban Orlando, but I doubt anyone has been so brazen as to steal an entire bowl from someone’s porch.) It’s just part of the culture, not too different from driving through the fanciest neighborhoods to see the coolest lights come Christmas.

A point I’d failed to make in the post, but intended to do so, was that taking excessive amounts of candy on Halloween isn’t a new problem. I was a kid once upon a time and I remember other kids doing that. It’s always a risk when you leave things out and expect people to act on their honor.

However:

But then I get to thinking… these people’s faces are being recorded. Presumably they know this. Our generation is aware that cameras are everywhere nowadays: on our doorbells, in our phones, on our dashboards, in our businesses, on our traffic lights, our ATMs, our stairwells, and so on. People rightfully assume they’re being recorded virtually everywhere they go, yet the threat of their identity being revealed seems to not to deter these profoundly antisocial acts. One would think that being more surveilled would result in more law-abiding behavior, yet the opposite seems to be happening among the youngest and most internet-savvy people.

I’d never thought of it like this. And it’s true - America’s as much a surveillance state as its ever been, yet it doesn’t seem to be making for a safer, more orderly society. Take a look at the screenshot of the group emptying that candy bowl - the woman stares directly into the camera, which is also quite visible, as you can see from the other photograph facing the door!

Why is that? Why does the fear of getting caught serve as no deterrence?

I can think of a few reasons why. Maybe too many of our peers got away with blatant criminality in the recent past. If your cousin stole a TV back in 2020 and never got caught, wouldn’t you be tempted to do something criminal yourself someday? Maybe people have discovered that the authorities have either lost the will to enforce the law or else can be completely overrun when places get mobbed en masse. Or maybe we’ve digested the reality that for many of us, our first instinct is to turn the other cheek and submit to humiliation rather than court a class- or race-based controversy. It’s probably less destructive for someone in a lucrative field (or a nice neighborhood) to be deprived of Halloween candy or be harassed by strangers than it is to be accused of racism.

As I said in this piece, either state or society maintains order. Ideally, the two entities work together to do so. But it needs to be at least one or the other. America is increasingly reaching a point where neither state nor society does. The only order we’re permitted to maintain is our personal order, but for how long can you run a society like this?

Kyle concludes:

Sorry if my comment doesn’t explicitly have to do with trust, I just felt like chiming in. It seems to me that we have more tools than ever to deter criminality, but the authorities and/or our neighbors lack the willpower to do anything about it. Obviously stealing candy isn’t that big a deal in the scheme of things, but it’s an indicator that the culture is changing—this behavior is likely to be passed on to that woman’s kids!

I think I said this a few posts back, but the problem in America isn’t that crime and disorder are out of control. Not yet. The problem is that crime and disorder isn’t dealt with properly when it occurs. It’s akin to the fire department failing to extinguish fires and instead opting to let them burn themselves out. But if you don’t at least contain the inferno, eventually, everything else catches on fire. I believe this is figuratively and literally what’s happening to America.

Like Kyle says, taking more than your fair share of Halloween candy isn’t the worst thing in the world. But the fact there’s nothing to stop it from happening is indicative of where we’re at as a society. If the fear of getting caught and getting publicly shamed isn’t enough to stop this from happening, there’s not a whole lot more that can.

We’re in the very uncomfortable place in time where we haven’t arrived at our final destination, but it’s also too late to turn around, nor is stopping an option.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

You say that high-trust societies tend to empower people to enforce social norms independently. My wife and I have experienced as homeschoolers. Homeschool groups are the last places on earth that any parent can correct any kid and know they will be backed up by that kid's mom. Try doing that at a public park and see what happens.

I wonder if you've read Why Liberalism Failed by Patrick Deneen? He believes that Enlightenment liberalism seeded its own destruction. Locke (and especially Mill later) placed maximal individual autonomy as his highest good. which makes any other "common good" standard (like a shared moral order) impossible, since any collective restrictions on my behavior violate my maximal individual autonomy and therefore must fall. Mill intended this; for Locke I think it was accidental.

"Personally, I’ll take the stronger culture over higher trust."

I agree and it was Patrick Deneen that showed me why it matters. Fixing trust levels is impossible. Fixing culture is only really hard. If you haven't read the book, you definitely should.

I stumbled across your page via Rod Dreher’s substack and have pored over at least a dozen of your articles. I want to commend you for your persuasive writing about crime and human nature, it’s really got me thinking…

I feel pretty comfortable assuming that the family stealing candy isn’t from the neighborhood. In my experience, it’s common knowledge that the ritziest neighborhoods have the best Halloween treats, so lots of teens and/or working class families make trips into the “nice” side of town in order to indulge in some fantastic candy. (At least, that’s what happens in my folks’ neighborhood in suburban Orlando, but I doubt anyone has been so brazen as to steal an entire bowl from someone’s porch.) It’s just part of the culture, not too different from driving through the fanciest neighborhoods to see the coolest lights come Christmas.

But then I get to thinking… these people’s faces are being recorded. Presumably they know this. Our generation is aware that cameras are everywhere nowadays: on our doorbells, in our phones, on our dashboards, in our businesses, on our traffic lights, our ATMs, our stairwells, and so on. People rightfully assume they’re being recorded virtually everywhere they go, yet the threat of their identity being revealed seems to not to deter these profoundly antisocial acts. One would think that being more surveilled would result in more law-abiding behavior, yet the opposite seems to be happening among the youngest and most internet-savvy people.

I can think of a few reasons why. Maybe too many of our peers got away with blatant criminality in the recent past. If your cousin stole a TV back in 2020 and never got caught, wouldn’t you be tempted to do something criminal yourself someday? Maybe people have discovered that the authorities have either lost the will to enforce the law or else can be completely overrun when places get mobbed en masse. Or maybe we’ve digested the reality that for many of us, our first instinct is to turn the other cheek and submit to humiliation rather than court a class- or race-based controversy. It’s probably less destructive for someone in a lucrative field (or a nice neighborhood) to be deprived of Halloween candy or be harassed by strangers than it is to be accused of racism.

Sorry if my comment doesn’t explicitly have to do with trust, I just felt like chiming in. It seems to me that we have more tools than ever to deter criminality, but the authorities and/or our neighbors lack the willpower to do anything about it. Obviously stealing candy isn’t that big a deal in the scheme of things, but it’s an indicator that the culture is changing—this behavior is likely to be passed on to that woman’s kids!