The Thinning Red, White, & Blue Line

It leads me to a question I’ve asked myself for many years: what if 9/11 happened today?

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Today, in remembrance of 9/11, I am re-running the essay I wrote a year ago for the first anniversary of that awful day since I started this blog. I got over 20 years of thoughts and memories off my chest in that piece and, for now, I do not feel there is anything more for me to say that I did not say a year ago. As my subscribership has increased tremendously since then (I cannot say “thank you!” enough), I feel this is as good a day as any for a re-run.

I hope you find this piece worthwhile. Feel free to share your thoughts and memories of that fateful day 22 years ago in the comments section. It was truly an SHTF, was it not?

Yesterday was the first anniversary of 9/11 since I started this blog. Like many Americans, particularly of my generation, it was and, until further notice, will remain the most significant and traumatic event of my lifetime. I haven’t really shared my thoughts on 9/11 anywhere before, primarily because everyone has a take on it and mine isn’t particularly novel. I’m just one of millions of Americans fortunate enough not to have been directly impacted by 9/11, but was ultimately affected by it in some small measure, nonetheless.

That said, I’d be silly to not use my forum to speak about that day, especially now that I have a captive audience in all my wonderful readers and subscribers. Let’s begin by unwinding the clock a bit.

I was in my mid-teens in the summer of 2001. It’s been said and will be said increasingly in the years to come, but this point of history was arguably one of the best times to be a kid in America. I won’t get into it any more than that, but I can tell you very few Millennials (the oldest “Zoomer” was only a few years old) were worried about the direction of the country or world events. If it wasn’t the height of the empire, it sure looked like it.

George W. Bush was in his first year as president. Hard to believe, but he’d been elected in arguably the most contentious election before the craziness that was 2020. Those who weren’t around for the 2000 election have no idea just how insane it was at the time, but, despite it all, the country managed to get through it without threats of civil war and secession, nor a riot at Capitol Hill. By summer 2001, people kept whatever hard feelings they had about the election to themselves and got on with life. Different times, indeed.

That summer, my family and I took a trip to the West Coast, including a detour to Las Vegas, seeing parts of the country we’d never seen before. The top summer movie was Rush Hour 2, which we also saw together as a family. Life wasn’t perfect, it never is, but it was good. Like a family member would later say, summer 2001 was “The calm before the storm.”

Then came that day. In retrospect, what stands out most to me is how pleasantly and quietly it started. Watch this video, but especially the bit at 2:34, when an anchor on CBS’ The Early Show observes that it’s “Too quiet:”

It was 8:31 am Eastern Standard Time when he said that. Exactly 15 minutes later, the first plane struck the North Tower of the World Trade Center (WTC). It’s been years since I first saw the video of the “too quiet” remark, but it haunts me every time I see it. I can guarantee that 9/11/01 wasn’t the first nor last day things seemed too quiet, but it needn’t be pointed out as it was. Somehow, it’s like the anchor felt in his gut something wasn’t right even before he knew it.

One of the worst days in American history and none of us saw it coming. Traumatic events rarely give us warnings (even if there are always warning signs along the way) and often strike us like a sucker punch out of nowhere. There’s a lesson: prepare for the worst, with the understanding you’ll never see it coming if it does. We didn’t know it at the time, but it was the first real grown-up lesson Life ever taught my generation.

I was getting my school year picture taken that day in the auditorium when I first heard about the attacks. I was standing in line and photographer was talking with students about what was going on. By this point, one or both of the Twin Towers had already collapsed and the Pentagon had been struck. I remember not being particularly surprised, which is a reaction I still cannot explain to this day, except to say maybe I just didn’t know how to react. Life doesn’t give you a playbook explaining exactly how you’re supposed to conduct yourself in the face of traumatic, unexpected events, you just draw upon the experiences and lessons you internalized along the way. Coming from a fairly stoic family, I supposed I merely faced the day’s events stoically.

Within hours, like most of the country, school was adjourned for the day. Another image burned into my mind was the look on my mother’s face when she greeted me at the front door. I can’t describe it, other than maybe a look of disappointment and that’s probably understating it. Even so, that look on her face said it all: something terrible had happened and none of us knew where any of this was headed.

The rest of that day remains a blur. It’s 9/12 which stands out to me more than 9/11 itself. We woke up and decided to visit a bookstore, many which had elected to remain open to sell newspapers (back then, we still read the paper!). On the way, I saw three to four separate motor vehicle accidents (all minor, thankfully), despite there being virtually no traffic on the roads! For me, personally, that underscored the magnitude of the previous day’s events. It was so jarring, so shocking, that people were still finding ways to get into car accidents despite there being literally nobody else on the road.

The next day stands out to me, also. After taking 9/12 off, it was back to business, if not as usual, on 9/13. I remember walking to school, wondering all the way what things would be like. I dropped off my stuff at my locker, grabbed what I needed for my morning classes, and made my way to the first class of the day. Along the way, I glanced inside classrooms as I walked by, listening carefully, trying to figure out what people were saying and thinking. I didn’t hear anything notable, but the atmosphere was noticeably subdued. It was strangely normal, yet you could tell something awful had happened. Everyone was trying to keep calm and carry on, but there was no denying we were in uncharted territory. There was something bizarrely comforting about the moment and I’ve often wished we had more moments like that, even as I understood the horrific price we paid to get it.

As our first class began, we all sat quietly in our seats. The teacher, whose name I won’t disclose, with a look of calm, pleasant, determination on his face, pulled up a chair, sat down in front of the class, and began by saying how he was glad we all had 9/12 off, because “I think we all needed that.” Truer words had never been spoken. We spent the entire morning talking about 9/11 and what would come next. I remember saying something about using special operations forces to take on the terrorists - once again, it was an understatement.

As I write this entry, reminiscing on events 21 years ago, I’m struck by how it all feels from a different lifetime. But it also feels like it happened last year. I used to lament how much time had passed between 9/11 and now, but not anymore. It was truly as horrible as we remember it, so the more time passes, the better. Yet it also serves as a touchstone for how this country, especially my generation, deals with the great challenges of our time. On this point, I’m not encouraged and it’s not just because of the War on Terror and everything else that transpired between then and now.

About that war: within a few years, the memory of 9/11 became strangely normalized to the point that the fact we were a nation at war had become lost on most of the population. Politically, the invasions and regime change missions in Afghanistan and Iraq became deeply controversial, with Americans wondering how much of our response was appropriate and how much of it was too much. But because the sacrifice wasn’t evenly shared, the concern was that this made it easier for policymakers to make bad choices and also creating a civil-military divide between the warriors and the protected.

I always found this a strange argument. First, there’s nothing to suggest that forcing more Americans to participate in the war or make more sacrifices would’ve delivered victory against the Islamists who attacked us on 9/11 or the insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq. That’s just not how these wars work. Second, the less people you expose to war, the better. The whole idea behind a professional, voluntary military, as opposed to a conscript force, is because the professionals do the job better and you minimize the loss of life. Over 10,000 Americans have died during 21 years of the War on Terror and, though tragic, is still a far cry from the over 58,000 who died within a similar timeframe in Vietnam. Not everything about the War on Terror was justifiable and Americans are right to question it’s effectiveness and even its righteousness, but, among the country’s wars, it’s proven among the least socially destabilizing and this should be viewed as a good thing, even as I concede it’s ultimate legacy remains to be seen.

What do I mean by this? Take a look at what our own media and Vice President said today, of all days:

https://twitter.com/BlazeTV/status/1568991100853190656

If you told anyone in September ‘01 that, 20 years from then, our own president and vice president would see Americans as the same kind of threat or even a bigger threat than the murderous jihadists who killed almost 3,000 people in a span of a few hours, you would’ve received a cold response at best, a hostile one at worst. The idea that we could ever turn on each other like this to the point even our national leadership suggests Americans be hunted down and killed as though they were terrorists was something you might’ve seen in “24,” but when it came to it happening in real-life, it seemed utterly insane. Yet, here we are. 20 years changes a lot of things, doesn’t it?

In retrospect, the 2000s were when the fissures that define some of our current divisions began to become apparent: the unity so emblematic of the days, weeks, and months following 9/11 evaporated in just a few years and we seemed more fractured than ever. Pres. Bush, who saw some of the highest approval ratings of any president in American history, was routinely called the second coming of Hitler in short order (sound familiar?) and would leave office one of the least popular, most derided ever presidents. Of course, the divisions and partisanship of the 2000s pale in comparison to that of today. A part of me wonders if we could lower the temperature to that of the ‘00s, that would be something we could all live with. I most certainly could.

It leads me to a question I’ve asked myself for many years: what if 9/11 happened today? Would we’ve responded the same way we did in the fall of 2001? My answer to that question has always been “no, it’d tear this country completely apart.” The reason I felt this way was because the divisiveness and partisanship that began to become so entrenched in the years following 9/11 cut so deep, there was no way those wounds could heal. It’s like being in a relationship and someone says something so cruel, so hurtful, it completely changes the way you look at that person.

Since 9/11, I believe Americans on all sides have dramatically altered the way they look at their fellow citizens and their country. If they didn’t already, we look at the man or woman next to us and we see a total stranger, someone we couldn’t possibly relate to, because political leaders have called them “unpatriotic” or “bigoted.” 9/11 was the last time the American Right held any cultural power in the country and boy, did they abuse it. It wasn’t possible to oppose the War on Terror, especially the invasion of Iraq, without having your loyalty to the country questioned.

Once the Left took control of our culture and politics for good, they held nothing back. While running for president in 2008, Barack Obama had this to say about Heartland America:

It's not surprising, then, they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren't like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.

The remarks were so jarring, even Hillary Clinton described them as “elitist and out of touch.” As the years went by, the rhetoric got more and more personal and pointed, making it impossible for us to ever back to a place where an election could end in chaos, like the 2000 election did, and yet we’d manage to eventually set it all aside and move on, saving the outrage for the next election.

Though the COVID-19 pandemic should never be compared to 9/11, despite the long-term death toll, it did give a good idea of how another national calamity would manifest for the U.S.: a brief period of shallow unity, followed within weeks by fierce partisanship. Everything, from masks to vaccines, became a political matter. Your partisan affiliation was defined by whether you continued to wear a mask and how many shots you got. The whole thing is so ridiculous and stupid, but it’s the reality we’ve been living with for two years.

The unfortunate truth is, we’ve come to despise ourselves and this country, another 9/11 would serve as an excuse to open a permanent rift, perhaps a reason to wage war on each other. I’m always struck by how quickly our social fabric became undone - 20 years, in the grand scheme of things, isn’t a long time - making me think it was done deliberately. We undid ourselves because we wanted to. Or was our social fabric never all that strong to begin with? Both explanations and their implications trouble me deeply.

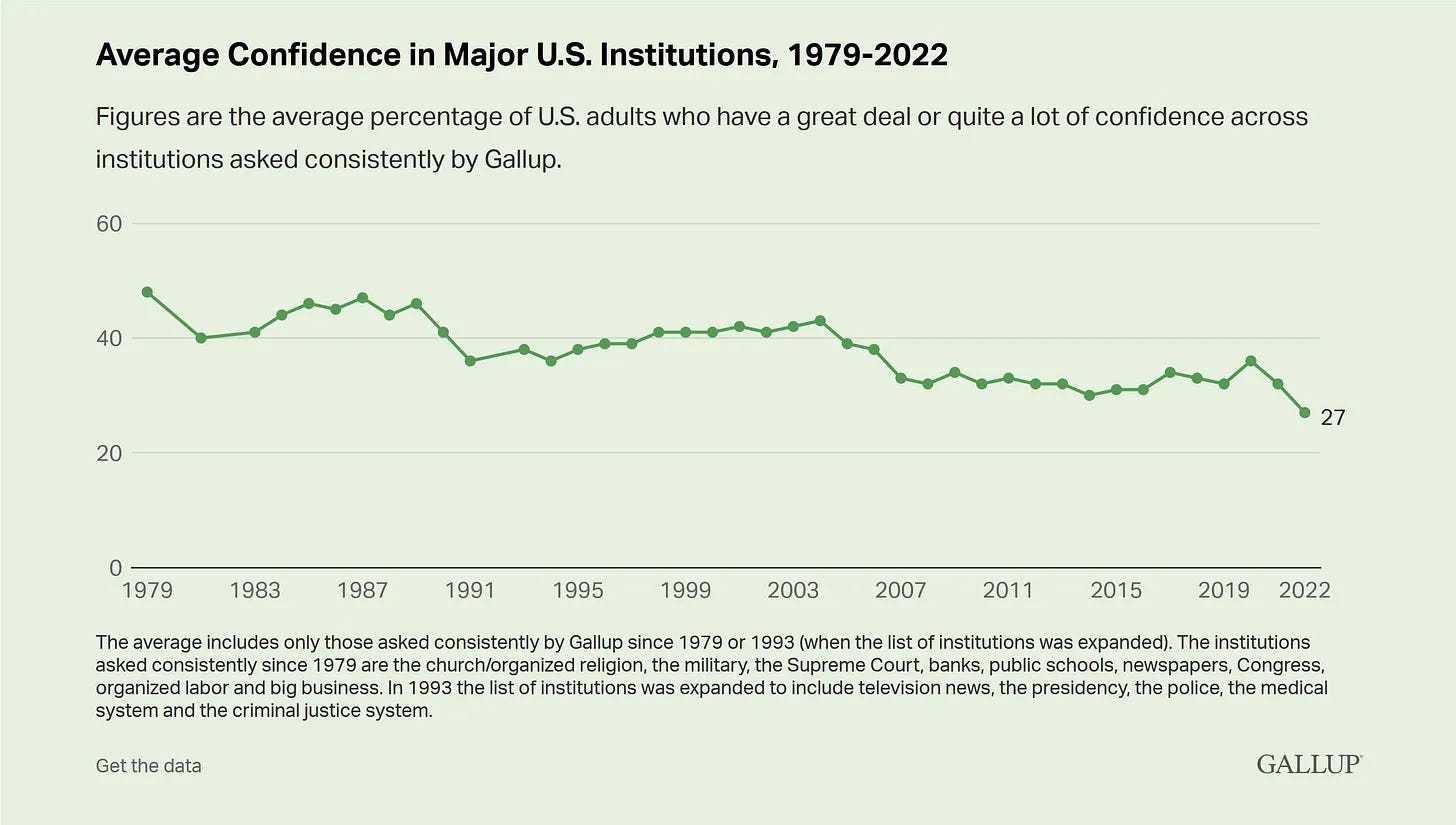

Retrospect also reveals that, for all the patriotism and unity we saw following 9/11, what we didn’t see was a major increase in trust in our institutions, even as we began to expect more out of them. I’ve noted before that Americans have seldom been one to trust our institutions to begin with, but it still stands out that even something like 9/11 couldn’t make it any better or worse at the time:

I mention this in part because of an article I came across yesterday concerning the challenges air traffic controllers across the country ran into in coordinating their response to the events of 9/11:

Before the full extent of the situation was even understood, Scoggins, Bueno, and fellow Boston Center air traffic controllers were already having to jump through procedural hoops to ensure that the right reports were making their way to the right people. In a scenario that later proved to be one of the most dire in aviation history, having to relinquish minutes of time to playing phone tag with the military understandably made it difficult for Scoggins and his fellow air traffic controllers to do their jobs in a timely manner.

Another factor was preparation and protocol. While the men and women working at Boston Center during these events were undoubtedly skilled in their roles, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the rules it follows and implements exist on a pre-and-post 9/11 timeline. The FAA underwent an unprecedented evolution following 9/11, one that actually began that very day when the agency helped completely shut down U.S. airspace in an act that had never before been executed before. Essentially, both Scoggins and Boston Center would have a hand in altering the trajectory of the FAA and how it operates — they just didn’t know it yet.

“There was no training to be the military liaison,” Scoggins said. “They either call you the military liaison or the military specialist. Each center is supposed to have one, and there are 21 centers in the country. Twenty-three if you consider Puerto Rico and Hawaii, and there is no training. You just kind of learn from what you’ve done in the past.”

More:

By 2001, with only his ATC training and personal experience with military procedures, Scoggins considered himself to have a pretty good handle on things. He would even say the same about his role on September 11, explaining that by the time the plane hit the second tower at the World Trade Center, he was sure the country was under attack by terrorists. However, he was only one person in what was an extensive chain of command, and up until that point, he describes a lot of bureaucracy and uncertainty.

In Uvalde, Texas, we recently saw a massacre unfold in part because the professionals we entrust to exercise violence on our behalf were conditioned into not taking action unless somebody specifically ordered them to. On 9/11/01, there was no shortage of people willing to take action and put it all on the line to save lives, but the bureaucracy still got in the way. A sense of duty and responsibility to your fellow countryman doesn’t seem to count for much when the system works against you. If the system was working against us 20 years ago, how much better do you think we’d fare in a 9/11-type event today, now that those serving us have no sense of duty or responsibility to this country? Think about it.

One of the ATCs interviewed in the article ends by saying:

“But I have to say, the biggest thing is that I know our passengers are never going to let anyone successfully hijack a plane ever again.”

We all think of United 93 when we hear about passengers rising up to stop the terrorists from striking their intended target. We think about the cruelty of it all, how 40 lives were extinguished by murderous savages. At the same time, I can’t help but be proud, to know such people existed and that they did not cower in the face of vicious monsters. Whether they made it to the cockpit or not is immaterial; they forced the terrorists to change their plans and that’s what matters.

In many ways, the story of United 93 is really the only thing left for us to hold onto from 9/11 - the realization that we the people are truly the first and last line of defense for this country. It’s easy to think that, placed in the same scenario, we’d all be as brave and courageous as the passengers of United 93. I don’t know about that. Tell me how confident you are your fellow Americans will “rise to the ocassion” when this sort of thing goes completely unchallenged, at an airport of all places:

https://twitter.com/1Fubar/status/1568852851535020032

Forget about facing down terrorists when you can’t even face this down:

https://twitter.com/realdanlyman/status/1568812806501179392

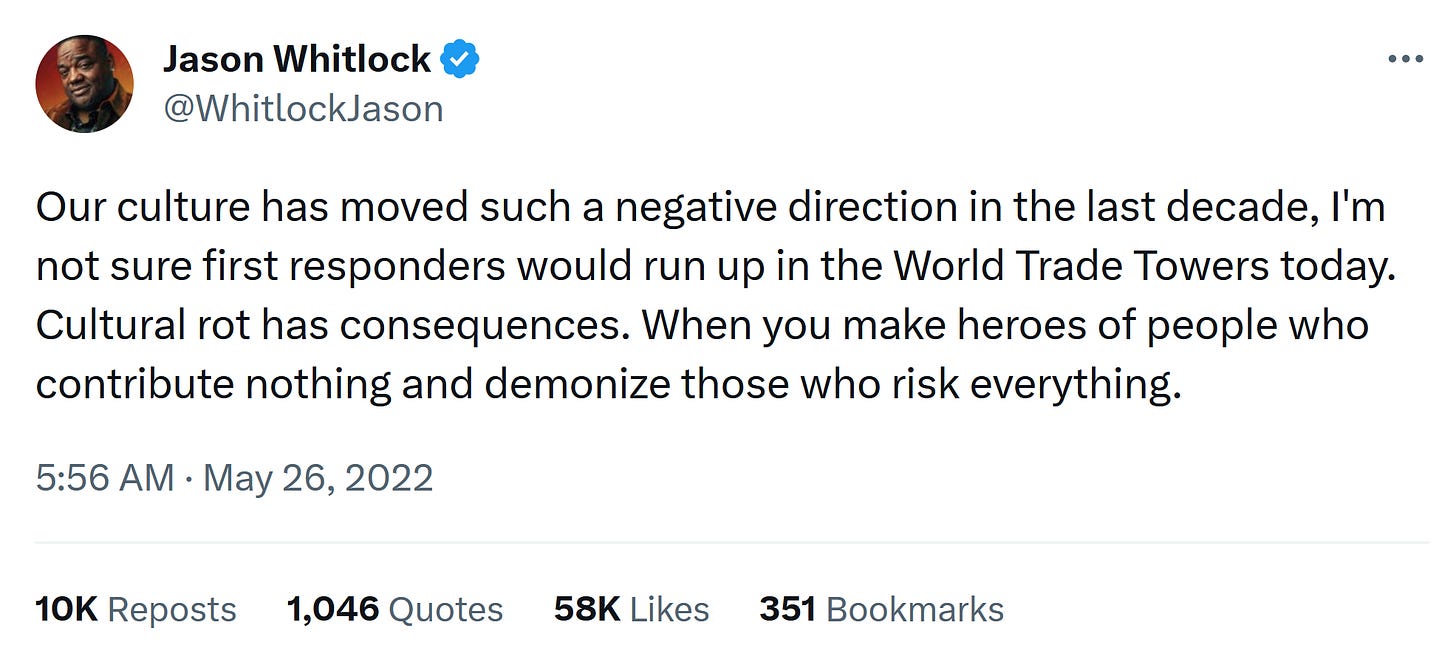

I hope I don’t come across as overly judgmental: it’s never my place to tell someone else they must put their lives in jeopardy for the public good. Under anarcho-tyranny, I can’t blame anyone for choosing the path of least resistance. What’s the point of protecting others when the state nor society would protect you? But that’s exactly the point - we’ve been so demoralized and disempowered I have no faith we’d ever see the kind of bravery we saw 21 years ago. Sportswriter Jason Whitlock said this following the Uvalde massacre - he ruffled a lot of feathers in the process, probably because what he says is true:

I hope I’m wrong. I hope there are still Americans out there like those on United 93, whose blood was spilled into the dirt of Shanksville, Pennsylvania. In fact, I know there are. But I also know there are fewer of them today than there’ve ever been. There may be 300+ million people in this country, but the real Americans constitute an ever-thinning red, white, and blue line.

I’ve turned this into a dump for my memories and deepest thoughts, most of which I haven’t shared elsewhere and am doing so for the very first time publicly. In some ways, I’m still processing 9/11, even as we, as a country, are running out of things to say about it. For now, it still remains the most significant event of my lifetime, even though I’m very certain, in the ‘20s, something else will become the new “9/11.” What and when remains to be seen.

I’ll leave you with something retired Army General Tommy Franks, who led the 2003 invasion of Iraq, said that same year about what he thought would happen if another 9/11 occurred in the U.S.:

If terrorists succeeded in using a weapon of mass destruction against the U.S. or one of our allies, it would likely have catastrophic consequences for our cherished republican form of government.

…

If the United States is hit with a weapon of mass destruction that inflicts large casualties, the Constitution will likely be discarded in favor of a military form of government.

…

The Western world, the free world, loses what it cherishes most, and that is freedom and liberty we've seen for a couple of hundred years in this grand experiment that we call democracy.

It doesn’t matter if Franks was right about the militarization of our society in response to another cataclysmic incident. I don’t think he is. What matters is that he’s correct that it’d destroy whatever faith we have left in the Constitution and the country.

But don’t take my word for it. Look at where we’ve been and where we are today and draw your own conclusions. Speaks for itself, doesn’t it?

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

At the endings of "High Noon" and "Dirty Harry," the hero throws away his badge, his judgement upon the underserving public he just risked his life to save. I now sympathize with those characters.

I've given up believing Singaporean-style techocratic excellence will ever be achieved by a multi-racial open borders liberal democratic West. I personally devote daily effort to spread neoreactionary seeds wherever the online right congregates - gateways to the neoreactionary canon and aesthetic and spreading seeds of discord, doubt and gaslighting demoralization whever the regime tries to cheer up its rank and file. The quote that drives me is from Moldbug: "The Stasi Officer was the most prestigious job in all of East Germany until one day, it wasn't."