This S**t Is Bananas! B-A-N-A-N-A-S!

It’s tough to argue against holding political leaders accountable - I wish we’d do it more often - but it’s a fact of life that doing so correlates with political instability.

Before I begin, please forgive the obnoxious title. Coming up with titles for blog entries is tougher than you imagine and, given the subject matter of the following post, the first thing that came to mind were the lyrics of Gwen Stefani’s (unfortunate) 2005 hit single “Hollaback Girl.” I resolve to become better at coming up with titles; I’m ashamed to say I often hold up publishing a post because I cannot some up with something appropriate and sufficiently eye-catching. Feel free to offer any counsel on how to better formulate titles, readers.

To the topic at hand…

In a stunning turn of events, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) executed a search warrant on Monday of former President Donald Trump’s residence in Mar-a-Lago, Palm Beach, Florida. The warrant is apparently unrelated to the January 6 investigation, instead concerning suspicions Trump took with him classified material when he vacated the presidency and the White House in January 2021.

I’m writing this post over two days after the raid began and the situation isn’t any clearer now than it was at the start, given Trump has elected to plead the Fifth Amendment and divulge no further details on the situation he finds himself in. For now, I’m inclined to give the FBI the benefit of the doubt, not because they deserve it (they don’t), but because without any further details concerning the warrant, it’s impossible to render any kind of judgment. As someone explained, a warrant of this magnitude against an ex-president would’ve had to been approved at the highest levels. The FBI and Department of Justice are putting every last shred of credibility they have remaining on the line here:

Tough as it may be, I implore you: withhold judgment. Nobody is above the law and, in that respect, it’s kind of nice to see the state take action against a former president. If only they did this sort of thing more often against a wider array of figures.

And that’s where it begins to smell wrong. Even those not in Trump’s corner have reservations about it:

The important thing to remember is that Trump isn’t the only person to have engaged in corruption or possibly criminal behavior while in office. The Hunter Biden scandal isn’t only far more serious than the media wanted to admit, but it’s apparently not limited to Hunter, appearing to implicate the current president. How far is the Justice Department willing to go to investigate the allegations? Or are they willing to investigate at all? Unless what Trump did was so beyond the pale, neglecting to pursue him by any means necessary would itself be a criminal act, the Mar-a-Lago raid seems a political move, given the Regime’s burning hostility towards Trump. The adage when you aim for the king, you best not miss explains a lot of what happens in Washington. The tremendous clout possessed by Biden or the Clintons and Obamas makes pursuing investigations against either a high-risk maneuver, while Trump, a total outsider and completely isolated politically, is fully exposed, making him an easy target for the Regime.

The FBI raid signals a potential turning point in the history of our country and there’s nothing hyperbolic in saying so. For starters, this is the end of politics as usual. Right or wrong, ex-presidents have generally been considered off-limits for prosecution, unless, again, the crime was so egregious it would be a miscarriage of justice not to investigate and pursue charges (think capital crimes, like murder or rape). In many ways, the lack of accountability has contributed to the overall stability of the system. Much of this is due to the peculiarities of American culture. In South Korea, for example, where honor is a sacrosanct value not limited to just the military, two of the last four presidents have been charged, convicted, and imprisoned. It’s nice to think that we can hold our leaders accountable to the extent South Korea does, but there’s no telling what sort of impact it’d have on U.S. politics if we did.

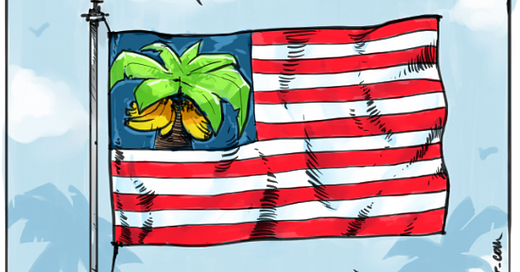

Actually, we do know. Sort of. A term we’ve been hearing a lot since word of the FBI raid was announced is “banana republic.” Here’s former Democratic congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard using it:

While I share her concerns, she, like many others, misused “banana republic.” If you’ve been following me at all for any length of time, you know how important I find it to be precise with terminology, especially when it refers to something specific. The generally-accepted academic definition of banana republic is:

a small, poor country, often reliant on a single export or limited resource, governed by an authoritarian regime and characterized by corruption and economic exploitation by foreign corporations conspiring with local government officials.

any exploitative government that functions poorly for its citizenry while disproportionately benefiting a corrupt elite group or individual.

The U.S. is a lot of things, including a kleptocracy, among the most corrupt forms of government imaginable. However, it doesn’t meet the other components of the term’s definition. America is certainly not poor, our economy doesn’t rely on a single export or limited resource, and despite creeping authoritarianism, the U.S. state is, thankfully, still a good ways off from being a truly authoritarian regime, compliments to the Constitution. And until we know exactly why the search warrant was initiated, there’s no way to know whether this was a political move against Trump or not.

But calling the U.S. a banana republic is useful in one respect. The term is often used, most accurately, to describe a Latin American country. This is because the term itself originated as a descriptor of countries like Guatemala and Honduras when they were effectively economic colonies of countries like the U.S.:

Latin America is a region notorious for political instability. It stands out because the continent consists of a mix of developed- and developing-world countries, with none of them your prototypical Third World land. Yet Latin America shares the same hemisphere of the globe with the U.S. and has more in common with America than it does with most European countries.

For one, we share a similar form of governance with many of our neighbors to the south. The U.S. is a federal presidential republic and so are Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Even the countries which are not federal republics, but instead unitary states (where the central state governs the entire country) like Bolivia, Chile, and Colombia, are all presidential republics. With the exception of Canada, the parliamentary system which dominates so much of the world is virtually non-existent in the Western Hemisphere.

What’s the significance of this? In 1990, the late political scientist Juan Linz wrote an essay titled The Perils of Presidentialism, where he made a troubling observation [bold mine]:

Indeed, the vast majority of the stable democracies in the world today are parliamentary regimes, where executive power is generated by legislative majorities and depends on such majorities for survival.

By contrast, the only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States. The constitutions of Finland and France are hybrids rather than true presidential systems, and in the case of the French Fifth Republic, the jury is still out. Aside from the United States, only Chile has managed a century and a half of relatively undisturbed constitutional continuity under presidential government-but Chilean democracy broke down in the 1970s.

More:

The burden of this essay is that the superior historical performance of parliamentary democracies is no accident. A careful comparison of parliamentarism as such with presidentialism as such leads to the conclusion that, on balance, the former is more conducive to stable democracy than the latter. This conclusion applies especially to nations with deep political cleavages and numerous political parties; for such countries, parliamentarism generally offers a better hope of preserving democracy.

I’ve searched far and wide; The Perils of Presidentialism is difficult to find in its entirety. Thankfully, there’s a 2005 paper co-authored by Mr. End of History himself, Francis Fukuyama, which summarized Linz’s argument succinctly [again, bold mind]:

Juan Linz, in his classic article in the Journal of Democracy, laid out four major “perils of presidentialism.” First, the inherently winner-takeall [sic] nature of presidential elections can too readily produce a president who enjoys the support of only a minority of the electorate and hence suffers from a legitimacy gap. Second, the rigidity of presidential terms and the difficulties in removing a sitting president make change in the executive excessively difficult, and term limits may turn even popular and effective incumbents into lame ducks. Third, the “dual legitimacy” of elected executives and legislatures often leads to policy gridlock when the two branches are captured by different parties or when presidents fail to muster solid legislative majorities to support their agendas. Finally, presidentialism can foster “personality politics” and make it possible for inexperienced outsiders to rise to the top.

The last point has been thoroughly vindicated by the rise of Trump. Bear in mind, both Linz’s original essay and the critique by Fukuyama et. al. came at a time when Trump had either little to no serious political aspirations or was coming off a failed bid for the presidency. If they were that far ahead of the game then, why wouldn’t they be right about presidentialism in the U.S. potentially going the way of Latin America? Look at this short list of countries in the region which have lived under authoritarian rule in just the last 50 years:

Argentina (1976 - 1983)

Brazil (1964 - 1985)

Chile (1973 - 1990)

Honduras (military governance from 1963 - 1981).

Mexico (functionally a dictatorship with one-party rule between 1929 - 2000, complete with political repression)

The region is convulsed by political crisis and mass civil unrest on a cyclical basis. What happened in the U.S. in the summer of 2020 in response to the death of George Floyd in police custody is something which happens fairly regularly in Latin America. It’s difficult to imagine the normalization of unrest on that scale, but it’s a part of life for our southern neighbors. Eventually, the authorities crack down, often resorting to brutality making that of the police in the U.S. pale by comparison. Often times, the military gets involved in restoring order. Meanwhile, in America, we’re not sure if the military should take the side of law and order or if it should take the side of insurrectionists and the forces of national disintegration.

Latin America is war-torn, even as authorities attempt to hide the fact to attract investment and tourists. The Mexican drug war is among the most lethal armed conflicts in the world, rivaled only by ongoing wars in Yemen, Myanmar, and of course, Ukraine. The war is of such a nature that most Mexicans and Americans can largely ignore it and go about their daily business without thinking about it, but it’s happening. There are also ongoing low-level conflicts in Colombia, Paraguay, Peru, and in the infamous favelas of Brazil. Their origins go back decades, some of these countries having suffered brutal civil wars during the 20th century.

I’m beginning to stray off topic here. The fact is, the presidential system of governance has a track record of failure. I’m not sure American exceptionalism will help us avoid a similar fate, especially as America becomes increasingly unexceptional. The last few years have proved we aren’t immune to political instability and the level of division and polarization in this country are reaching uncomfortable highs. Not to mention the kleptocratic nature of our existing regime suggests we’re already on a track towards authoritarian governance. There is something about presidentialism which seems to inevitably lead to it.

Back to Trump, Latin American politicians are infamous for corruption and criminality, often finding themselves charged, convicted, and sent to prison. Jeanine Áñez, who served as Bolivia’s president from 2019 to 2020, is currently serving a ten-year prison sentence for her actions following the 2019 presidential elections in her country, which ended in chaos due to allegations of fraud and led to mass unrest that killed 33. There was Alberto Fujimori of Peru, who served as president from 1990 to 2000 and was convicted of, among other charges, human rights abuses. Now 84, he’s currently serving out what amounts to a lifetime prison sentence. Then there are those who need no introduction: the long line of dictators, or Caudillos, and military juntas that governed Latin American countries with iron fists. Whether it was Augusto Pinochet of Chile or the National Reorganization Process of Argentina, many have suffered and died under their rule and scars remain to this day, some wounds never quite healing despite the amount of time that’s gone by.

It’s tough to argue against holding political leaders accountable - I wish we’d do it more often - but it’s a fact of life that doing so correlates with political instability. Whether corruption causes instability or vice versa doesn’t make a difference. At this stage of the game, suddenly choosing to hold someone like Trump, a total political outsider and not a member of the Regime, accountable sends a message other than merely stating “Nobody’s above the law.” Rod Dreher explains here:

Y'all know that I am not a Trump fan, but in this case, I can't separate the raid on his house from the rest of the rottenness of our ruling class. I am reminded of something I've repeated in this space a lot since I heard it last summer in Budapest. I was talking in a taxi with a younger voter who told me she planned to vote for Viktor Orban's party in the spring election. I asked her why, and she spoke at length about how fed up she was with what she believed was Orban's tolerance for financial corruption among his supporters. So why do you stick with Orban? I asked. She talked about culture -- specifically, about gender ideology that the European Union was trying to push onto Hungarians, but which Orban was fighting tooth and nail. She put it something like this (I paraphrase): "All corruption is bad, but not all corruption is equally bad. Financial corruption is normal. The moral evil of gender ideology is on a totally different level. If we accept that spiritual and moral corruption, we are finished.”

I guess the point is, if we really believe our ruling class weren’t above the law, we’ve had a long time to show how serious we were. No matter what Trump did, unless he literally murdered someone (something he foolishly once said he’d get away with, even if he were saying so in jest), what’s happening to him now opens the floodgates for pursuing all-out political warfare. If Republicans take control of the House in November, you can expect them to relentlessly pursue impeachment against President Biden and overwhelm the Clintons and Obama with all sorts of investigations concerning their past misconduct. They’d be foolish not to.

If you think Washington is dysfunctional now, wait until our elected leaders spend all their time, instead of some of it, trying to hurt the other side. Then we’ll see a level of gridlock we never thought imaginable, except in places like Latin America. Given enough time, even those of us who spend all our time talking about the importance of “protecting our democracy” will begin to support increasingly autocratic figures who sell stability over chaos.

Will we see our own Pinochet in our lifetimes? Will American exceptionalism give way to the reality that our system of governance is actually an exercise in futility? The only thing that’s for sure is America may not become a banana republic, but our politics are most certainly about to become more bananas than ever before.

Which I suppose would sort of make us a banana republic. Mea culpa.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!