You Don't Love What You Won't Fight For. You Won't Fight For What You Don't Love.

“Defend everyone else except your own country” seems to be an increasingly prevalent sentiment. How did we get here?

Once upon a time, I was sitting in on a lecture delivered by military historian Jon Sumida, who taught us that the two most important questions in the study of war are the following: Who fights, how much, and why? Who pays, how much, and why?

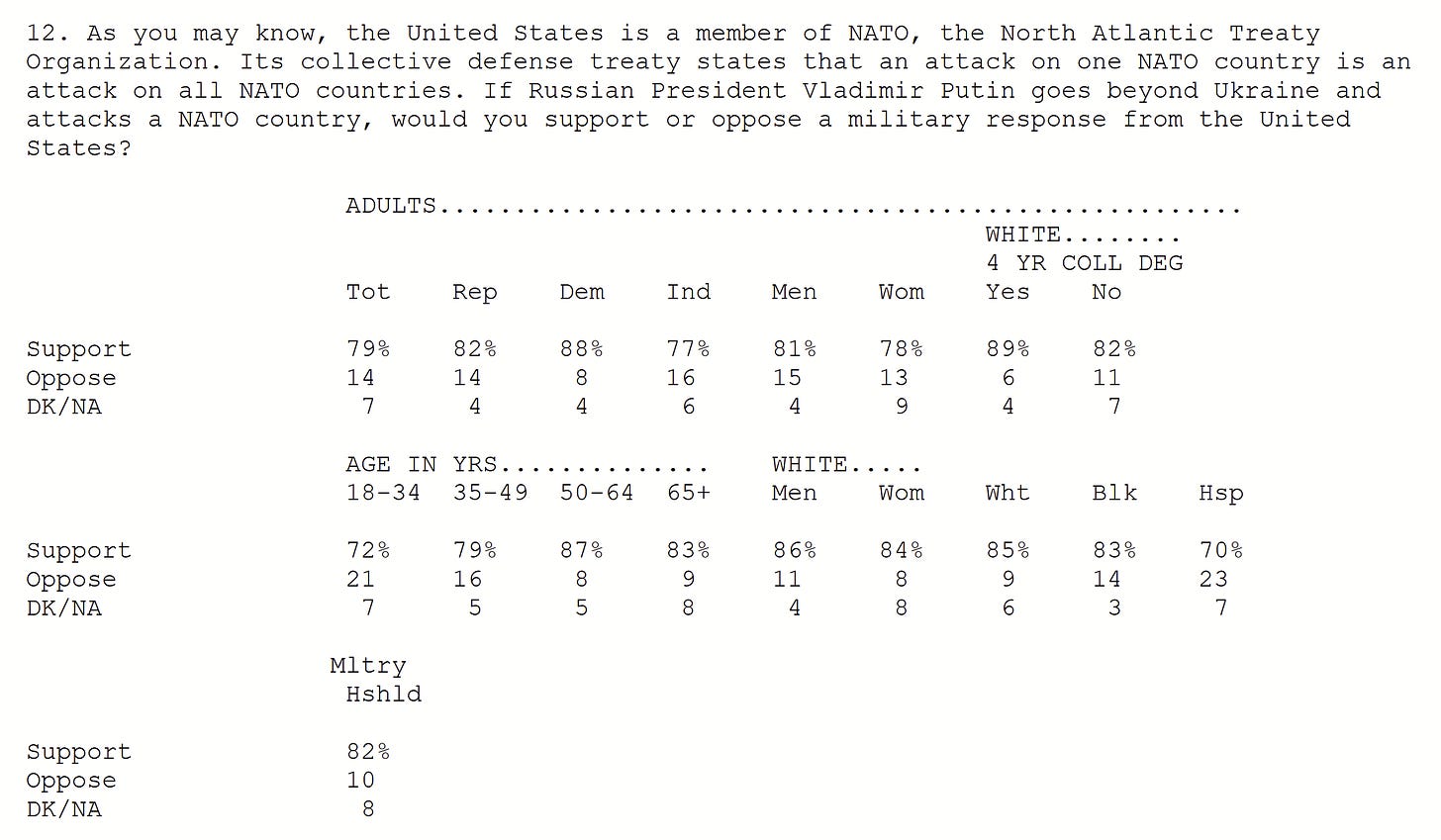

What the scholar said came to mind after looking at the results of the following poll concerning the situation in Ukraine.

For some, this proves the old maxim: Rich people start wars, poor people fight them. I don’t have the data readily available to show how the sentiments expressed in this poll track with that of past wars, but what’s important is that this is how people feel right now. Enthusiasm for U.S. military involvement in Europe is uncomfortably high, as I’ll explain in the next paragraph, but it’s also true that enthusiasm wanes the lower you get down the socioeconomic ladder.

As a whole, Americans occupy two separate camps simultaneously concerning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, we overall perceive Russia as an adversary and the clear-cut aggressor in the current situation. However, there exists little support for direct U.S. military intervention in Ukraine, a sentiment the president himself shares:

So, that means we’re in the clear, right? Well, it gets a bit more complicated. Notice the president starts his tweet by saying “We will defend every inch of NATO territory.” He doesn’t have much choice but to say this, as NATO is a defensive alliance that legally requires the U.S. to come to the aid of member states should they come under attack. A Quinnipiac University Poll reveals 79% of respondents would support a U.S. military response should Russia attack a NATO member state. Again, there’s really only one answer to the question, given the treaty-bound obligation of NATO membership.

What really stands out are the responses to the following question: If you were in the same position as Ukrainians are now, do you think that you would stay and fight or leave the country?

These were the responses, further broken down along gender, partisan, and racial lines:

Yes, a decisive majority of Americans would stay and fight for their homeland. However, 38% who wouldn’t is not an insignificant share. Most glaring is how a decisive majority of Democrats and young Americans would run for the exits. It’s not surprising, honestly, given what we know about both Democrats and the 18-34 age group. It just doesn’t quite fit, given their enthusiasm for upholding their commitment to NATO, a multinational alliance, and for paying higher gas prices for the opportunity to stick it to Russia:

As an aside, I highly doubt these sentiments concerning gas prices will last. It’s easy to say you’re willing to make sacrifices before needing to actually make sacrifices, but, once gas prices really start to take a bite out of Americans’ paychecks and the fate of Ukraine becomes bleaker, it’ll be very difficult to sustain this sentiment over the long haul. If nothing else, notice how many anti-COVID hawks and vaccine and mask-wearing enthusiasts among the public were eager to dispense with masks and social distancing once the state began to back off from battling a supposedly civilization-threatening pandemic without even declaring it defeated.

The numbers may not speak entirely for themselves, but they don’t lie, either. Americans, as a whole, including overwhelming majorities of Democrats and the 18-34 age group, have more enthusiasm for defending Europe and Ukraine and hurting Russia than they do for defending our country and way of life. “Defend everyone else except your own country” seems to be an increasingly prevalent sentiment. How did we get here?

This is a question I’ll likely revisit in future posts. The topic is loaded and there’s far too much to unpack in this post alone. However, I’ll say that while it’s too simplistic to say Democrats and young people hate America, it’s also very obvious, despite all the complexities inherent in human opinion, that both groups harbor very mixed feelings towards this country. I think I’m over the target when I say they consider America a nice place to live and work, but aren’t particularly invested in this country beyond what it has to offer them, the same way they’d treat any product or service. Once it’s outlived its usefulness, it’s time to move on to something bigger and better. In other words, America’s a house, but not a home.

Surely, there are many Democrats and young Americans who harbor outspoken contempt for this country. Others, however, would say they, in fact, love this country, they’re merely ashamed of its history and they believe what makes this country great isn’t the same as what the rest of us believe makes this country great. Specifically, America’s racial history diminishes our greatness, but we can become great as long as we accept anyone and everyone as “American,” if they want to be.

It all sounds innocent and righteous. Yet, it’s precisely this sentiment which inevitably leads to things like the poll results shown above. America’s past, while sordid, isn’t all that exceptional compared to that of other countries. However, it has overcome its past in ways so many countries still struggle to do so. If our history is something to be ashamed of and indicts this country, then atonement comes only in its destruction or its transmogrification into something totally different, entirely divorced from its past. Either way, it’d mean the death of a nation. I’m not saying that’s what Democrats and young Americans want, but that’s certainly where their thinking leads.

Likewise, the concept of America as an “idea” as opposed to people, places, and things is deeply problematic - if it’s merely an intellectual property, then why couldn’t you just package “America” up and take it some place else? After all, ideas can be transmitted, packaged up, and shipped elsewhere, can they not? This whittling down of American citizenship and nationhood as something meaning anything as to mean absolutely nothing makes this country… what, exactly?

The “hyphening” of America - where one’s ancestral background is of greater social prominence than your nationality - along with extolling the act of immigrating to the U.S. as a literal virtue, an entitlement, and something to be rewarded (even if done illegally) all at once, is both the intent and output of cheapening the value of citizenship. If America is forever a “nation of immigrants,” a perpetually empty vessel always in need of being filled, then assimilation and becoming a citizen serves no purpose - what’s the point, anyway, when you’re always going to be a newcomer? When America is anything and everything, it leaves us with no common culture, no common history, and, therefore, no common destiny.

This is the end result of decades of propaganda and concerted attempts to reduce our sense of nationhood to something entirely open-ended. It might’ve been done with good intentions (i.e., to be more accepting of newcomers), but the results of the Quinnipiac poll reveal what the policy has wrought in reality: a lack of personal investment and patriotism among members of America’s largest political party and the country’s young.

It’s one thing to say it isn’t worth dying for some abstract cause like democracy overseas. I happen to agree with that sentiment. But we’re talking about our home, our way of life. No matter what the cosmopolitans say, these things aren’t easily replaceable. Perhaps a reason why assimilation isn’t easy for migrants is because, well, America might be a wonderful place, but it’s still not home for them, yet. Immigrants have no history in their new country, that history exists elsewhere. Just as newcomers struggle to learn a new language and adapt to new ways of living, even cosmopolitan Americans will find it difficult to do the same in other countries, making it incredibly foolish to think they can just uproot themselves and start a new life somewhere else.

These attitudes don’t bode well for the future of this country. Many, myself included, would point out that the likelihood of the U.S. being invaded by a foreign adversary is low, but that’s not the point. A country where such a large and, possibly, increasing number of people unwilling to fight and die for it is a country that won’t defend itself from anything, period. Not from the tidal wave of illegal immigration coming over the southern border. Not from the cultural revolutionaries who harbor genuine malice towards this country (they work in the media, the universities, and even our government) and are destroying our national memory and demoralizing the populace. Not from the anarcho-tyrants who, instead of governing us, unleash violent predators upon society in the name of social justice.

You cannot defend what you don’t love. You will not die for something you don’t find redeemable or worthwhile. It’s that simple and I challenge anyone reading this to tell me why I’m wrong.

Still, all isn’t lost. Again, most Americans would stay and fight for this country. The 38% who would run away are probably better off doing so, as they’d either be of no use or they just might betray this country, proving themselves our sworn enemies. It’s inspiring to know the 55% who would remain and fight are Heartland Americans like Bryce Mitchell, an MMA fighter who had this to say about the situation in Ukraine. I won’t paraphrase what he said here, you have to listen to it (it’s a short video):

You don’t make America better simply by showing up, setting foot upon this soil, and participating in the daily hustle. This childish mentality is the same one which says everyone should get a trophy for participating. Instead, you make America better by building something worthwhile and defending it, while assimilating and upholding our core, founding values and history in the process. Is someone who makes a lot of money participating in the economy, while harboring resentment towards the country over its history, equally patriotic to the person who might contribute less to the economy, but is proud to be a citizen and will stand aside it even in its darkest hour?

America isn’t just some open-ended idea, nor is it the whole world. Like any other nation, it’s the product of a unique culture, heritage, language, and set of values that may have its origins elsewhere, but converged here to create something without precedent and without equal anywhere in the world. It can only embrace so much change before it starts to become something entirely different, a simple fact of life impossible for millions of Americans to grasp, but such is the nature of indoctrination and propaganda.

In closing, I want to share something I wrote last year in a review of the Matt Damon-headlining movie Stillwater (which I highly recommend to viewers). It concerns a line of dialogue which critiques the tragic stubbornness of Americans:

One of the first lines of dialogue in “Stillwater,” which opened in theaters July 30, is from a Spanish-speaking migrant worker expressing amazement at the idea that Americans simply come back, rebuild, and carry on despite tornadoes repeatedly levelling their town. The worker wonders why residents don’t just go someplace else to avoid this regular devastation to their lives.

It’s a fair observation, although anyone making such a critique, particularly someone who’s left his home seeking greener pastures, ought to be reminded that it’s often the stubbornness of people that builds places we can call home in the first place.

52% of Democrats, 48% of 18-34 Americans, and 38% of the public overall would abandon this country when it comes under direct attack. Their sentiments are unfortunate, but not quite as tragic as the fact they’d export the same lack of investment and patriotism on an unwitting victim somewhere else in the world.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!