The Brazilification Of America

Brazil, like most of Latin America, is desperately trying to avoid falling back into the clutches of authoritarianism, which is why so much rides on these elections.

The other day, I introduced you to Fabian Ommar, a Brazil native who comments on preparedness and survivalism. I’m sure glad I discovered him, because in such a short time, I’ve found his commentary to be as fascinating as any I’ve read.

Ommar being from Brazil is a critical aspect of his commentary because of his country’s history of periodic civil unrest, rampant crime, and political instability, similar to much of Latin America. We don’t place Brazil in the league of a country like, say, Lebanon nor Iraq, but it’s an example of how an overall developed, modern country can still be a chaotic, disorderly place to live. Brazil, like all countries, is a product of its own unique culture, geography, and history, but I find it a better example of what America’s future looks like than some of the more absurd comparisons made to Lebanon and the former Yugoslavia.

Recently, the world’s seventh most-populous country held presidential elections. According to the election results, the incumbent and right-winger Jair Bolsonaro was defeated by the challenger and left-winger Lula da Silva. Like the 2020 presidential election and the recent mid-terms in the U.S., the Brazilian election was mired in controversy and allegations of fraud. Unlike the U.S. however, fraud allegations are nothing new. Democracy has always struggled to find a firm foothold throughout Latin America, with many countries having transitioned away from authoritarianism just within our lifetimes.

Americans should pay more attention to Brazil and Latin America as a whole and not just because of the elections. The reasons are broad and beyond the scope of this entry, which is to share what Ommar, the man on the ground, has to say about what’s happening to his country post-elections. It’s enlightening and has much to say about what’s going on in our own country.

He begins by saying “there’s no revolution, much less civil war on the horizon,” much the same as he assessed of the U.S. This arguably good news for Brazilians, but again, our existence isn’t one of either total peace or full-blown civil war:

After a highly tense, divisive, and contentious campaign, incumbent right-wing Jair Bolsonaro lost the presidential runoffs on Sunday, Oct. 30, to former leftist president Luis Inácio “Lula” da Silva by a razor-thin margin (1.8%).

Brazil’s voting process is entirely electronic, and the results were announced in the afternoon, hours after the election ended. Almost immediately, truck drivers shut down motorways – more than 200 all over the country. On Tuesday, right-wing activists swarmed the streets of all 27 states’ major and minor cities.

The movement started spontaneously and appeared to have no clear, organized leadership or backing. Though I wouldn’t be shocked if that was the case: there are no power vacuums nor innocents in politics.

Although there is no official count, estimates talk about hundreds of thousands in larger centers and millions across the entire nation. The images are impressive indeed, showing huge and agitated crowds. Peace prevailed, though, with only isolated incidents of violence and shortages, thankfully nothing serious or long-lasting.

I’m glad to report that things are normal right now, or as normal as they can be in 2022.

The mayhem and apocalypse are only taking place in the news and on social media. Everything “real” is up and running: supermarkets, parks, stadiums, colleges, offices, gyms, farms, and factories. People are working, studying, dining out, and jogging (and preparing for the World Cup, which begins in a few days. After all, Brazil is the “nation of soccer.”)

In other words, it hasn’t hit the fan.

A couple of observations: one, it’s interesting to hear that Brazil has moved to an entirely electronic voting system. The U.S. utilizes a mix of electronic and paper voting and, unlike Brazil, elections aren’t administered nationally. Instead, consistent with the federalism under which the country was founded, the administration of elections is within the purview of the states. I’m not an elections expert and whether an all-electronic voting system is better or worse than America’s mixed system is beyond my capacity to assess, but it’s still interesting to note, given the two countries share the same system of governance (federal presidential constitutional republic).

It’s also worth noting that however strongly Brazilians may feel about the elections, like most people, they just want to get on with life. Barely a month had passed since the January 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol when Super Bowl LV took place; fans still attended and millions watched from elsewhere.1 Those of us deeply immersed in the big issues of the day often underestimate the extent to which, for most, life is just too short to worry about what’s going to happen to this country if so-and-so gets elected.

More:

But the situation is far from normal. Despite attempts by some official sectors with the collaboration of MSM to stifle dissent and keep the general public in the dark about the ongoing demonstrations, tension and discontent are palpable.

It took Bolsonaro nearly 48 hours after the results were announced to deliver his address, which did little to appease his supporters and the 58 million who voted for him. While not openly conceding, he never put up a fight or even came close to calling a coup, as his critics had predicted he would in case Lula won.

He was contained and circumspect to avoid fanning the flames of his supporters, deeming the protests “democratic and legit” but calling for the blockades to end at the same time. Bolsonaro reaffirmed his respect for the Constitution, stating many times he would play by the rules. Finally, he kickstarted the transition process.

Make no mistake: Bolsonaro is handling this correctly. Though he and his supporters may genuinely feel the election was stolen, as our own Donald Trump discovered after the ‘20 election, there’s no upside to screaming, “STOP THE STEAL” with only circumstantial evidence, conjecture, and a captive audience with which to back up your claims.

I quoted Scott McKay from The American Spectator two entries ago:

It’s tempting to fall into the trap of believing there must be wholesale corruption in American elections, but the problem with going there is that there must be proof before it’s actionable. [bold mine]

The American Right is talking a lot about ballot harvesting and other problems with voting in the U.S. I have to be perfectly honest, some of the arguments go over my head, but the complaints this time around seem less that elections were stolen and more that the process is unfair or at least vulnerable to fraud. One of the more convincing arguments American elections are compromised is the inability to count ballots in a timely manner. I’m not denying this is a problem in other countries, but it’s arguably a recurring issue in U.S. elections. The idea that our elections have to be mired in so much uncertainty for such an unreasonable amount of time - a week after the mid-terms, many key races, including governorships, remain undecided - is totally unacceptable for a country for which claims democracy as a sacrosanct principle.

However, the Brazilian experience reveals that squabbling over election processes distracts from the real crisis at hand:

It wasn’t a resounding victory for Lula.

Far from it, actually, and here’s why: voting is compulsory for eligible citizens living in Brazil or abroad, which means a universe of 156 million voters. Lula’s 60 million mean only 38% of the voting population actually supports him. That’s significant – and there’s no second place in politics – but still uncomfortably low for a newly elected president.

It spells significant opposition and a very short honeymoon for Lula and his allies going into 2023 and beyond, especially if the economy worsens (which has a very high probability of happening, as we all know).

Bolsonaro doesn’t have much going for him, either, having conquered only about 36% of valid ballots by the same calculations. In other words, when taking into account those who either abstained or canceled their vote, it becomes evident that neither candidate had significant support among the electorate and general population.

The logical conclusion? If Bolsonaro had taken the presidency on Sunday, we’d be witnessing the other part of the population protesting in the streets instead.

In ‘20, President Joe Biden won 51.3% of the popular vote, leaving then-President Trump with 46.8%. That same year, the number of eligible voters was 168.31 million Americans. This means Biden (who got more votes than any candidate in history) and Trump (who got more votes than any Republican in history) received electoral support from 48.3% and 44% of the electorate, respectively.

But unlike Brazil, the U.S. not only doesn’t mandate voting for all its citizens, it runs on a two-party system. Leaving aside the glaring issue of just 50% of the population being eligible to vote, Americans are forced to pick between a far narrower range of options. When compared to the population as a whole, Biden and Trump courted support from only 24.5% and 22.3% of the overall population, respectively. I’m not sure what to call this, but it’s definitely not mass democracy.

It’d be one thing if suffrage were afforded only to a certain segment of the population, but in America, the right to vote has been extended to nearly all and the trend, at least on the Left, has been to extend franchise to anyone who steps foot on this country, citizen or not. Yet, elections are still being decided by such a small portion of the population, calling into question the long-term durability of democracy even in a country that’s known nothing else.

The bottom line, according to Ommar:

That means people are weary, uninspired, and unsatisfied with the feeble, mediocre, dishonest, and inept leadership – from both sides. Which explains in good part the political polarization, extremism, and division.

We’re not in uncharted territory, not entirely. Apathy and turnout have been ongoing issues for generations, but it’s one thing if people are apathetic because things are going well. It’s another thing to be apathetic when things are clearly not going well. This means, even in the U.S., the direction of the country is becoming increasingly dictated by those whose views not only don’t comport with many Americans, but who are also among the most partisan. In politics, victory belongs to those who care enough to participate, but again, this undermines mass democracy, not strengthens it. On some level, democratic backsliding is a real issue.

Ommar had this to say about Bolsonaro and why he believes the incumbent lost the election:

Objectively, Bolsonaro has some positive economic statistics and achievements to show for him, but few were paying attention or felt moved by these. He wasn’t able to connect his accomplishments to his controversial figure and conquer support beyond his core constituency, to the point where voters chose to reinstall a known populist ex-convict with hanging charges instead of giving the incumbent a second term.

Hmm… sure sounds a lot like Trump, doesn’t it? 45’s presidency wasn’t all bad and, up until the whirlwind that was 2020, there was a fair chance he might’ve won re-election, though it would’ve been far from the “landslide” some erstwhile serious commentators rather foolishly predicted.2 But there’s no getting around the fact Trump was never a popular president (neither is Biden, but that’s a separate issue) and one's re-election prospects depend substantially on whether the public thinks you’re doing a good job or not. It’s for this reason I was never moved by Trump’s claims of fraud, as he was never popular enough to warrant re-election, anyway. I realize that may upset some of you who put all your hopes and dreams into Trump (and still do, as you’ll see), but I never stray from reality.

Again, the issue is far deeper than ballot harvesting or anything like that:

We can protest in droves against the lack of transparency while shouting at the top of our lungs about fraud and manipulation. Whether A or B wins, whether turnout is 100% or 10% – no outcome will be satisfactory because people no longer have faith in the system or the leadership. And these don’t give two craps for the wants and needs of the population, either.

This is an institutional as well as a political crisis, and it’s global. I have no crystal ball, but I’m willing to bet on a similar outcome for the US midterm elections (which should be over by the time this post goes live). There will be no massive red or blue wave; rather, a ripple and yet another letdown for radicals on both sides. Nobody will be assured or satisfied with anything. The same is occurring in all democracies. Tough times.

Ommar was right about the U.S. mid-terms. It was a “Red splash,” not the “wave” so many on the Right predicted. The days of a single party sweeping elections or presidents winning by landslides are over, the irony being the Democratic Party is likely to remain politically dominant given their fundraising abilities, the size of their voter base, public preference for their policies, and their presence within all the major societal institutions.

Still, expect elections to be ever more fraught and tightly contested going forward:

Back to the demonstrations, participants are protesting against censorship and requesting transparency from the bodies in charge of overseeing and administering the elections, more than directly endorsing Bolsonaro.

Even before the election, there was controversy about the Brazilian electoral system. In a true democracy, asking questions and demanding openness are legitimate demands. Yet, the Electoral Court (or TSE, an offshoot of the Supreme Court) is doing more to repress opposition and stifle open discussion than to offer satisfactory explanations and allow oversight that could placate a sizable portion of society.

These are precisely those whose responsibility is to uphold and defend the letter of the law and the Constitution to restore peace and foster unity among the population and other institutions whenever a contentious issue is at stake are doing the opposite of that.

Merely debating or questioning the process is now treated as a “coup plot” by these authorities and can get one criminally charged, persecuted, and censored. Like the voting system is some inviolable, infallible, incorruptible technology.

Trump went too far with his “Stop the Steal” effort in 2020 into 2021. But the act of questioning election results is hardly anti-democratic. How democratic of a process is it, anyway, if there exists no avenue for both election participants and voters to challenge results? No matter what Biden or anyone else on the Left says, elections aren’t some sacred ritual like a baptism or wedding. It’s a mechanism for implementing democracy and ought to be subject to review and scrutiny. Otherwise, it’s a shambolic process, a meaningless facade. Is this how the Regime wants elections to be viewed? If so, we’re in serious trouble.

Turning “election denial” into a partisan issue also isn’t smart, given the Left turned against elections long before Trump ever did:

Nor should democracy ever be regarded as sacrosanct when it permits such awful people to hold the reigns of power:

The protesters are also objecting to being once again governed by Lula and his clique. The charismatic and populist politician is still seen by a large percentage of the population, and even by many who voted for him, as a corrupt, cynical, and inept leader.

Lula governed Brazil between 2003 and 2011. In 2018, he was convicted of taking bribes from big contractors and sent to jail. He spent 580 days behind bars before the Supreme Court decided he may appeal his case without spending any time. He wasn’t acquitted, as he boasted during the campaign. His convictions were annulled based on a technicality. Many of the charges still stand.

But the fact is that Lula – the man who Obama referred to as “the guy” during a G20 conference in 2009 – was literally taken from prison and had his political rights reinstated just last year by the same Supreme Court justices who now preside over the TSE and were responsible for overseeing the electoral process.

Straight-up banana republic stuff. So yes, Horatio, if you see some suspicious connections in this muddle, you’re starting to understand what’s driving the protests.

I must hand it to Brazil - at least they attempt to hold their politicians accountable. The reality is that the lack of corruption in the U.S. is more perception than reality. If we held our politicians to a higher standard, or at least the standard we’ve held Trump to, American politics would appear far more corrupt than they do at the moment.

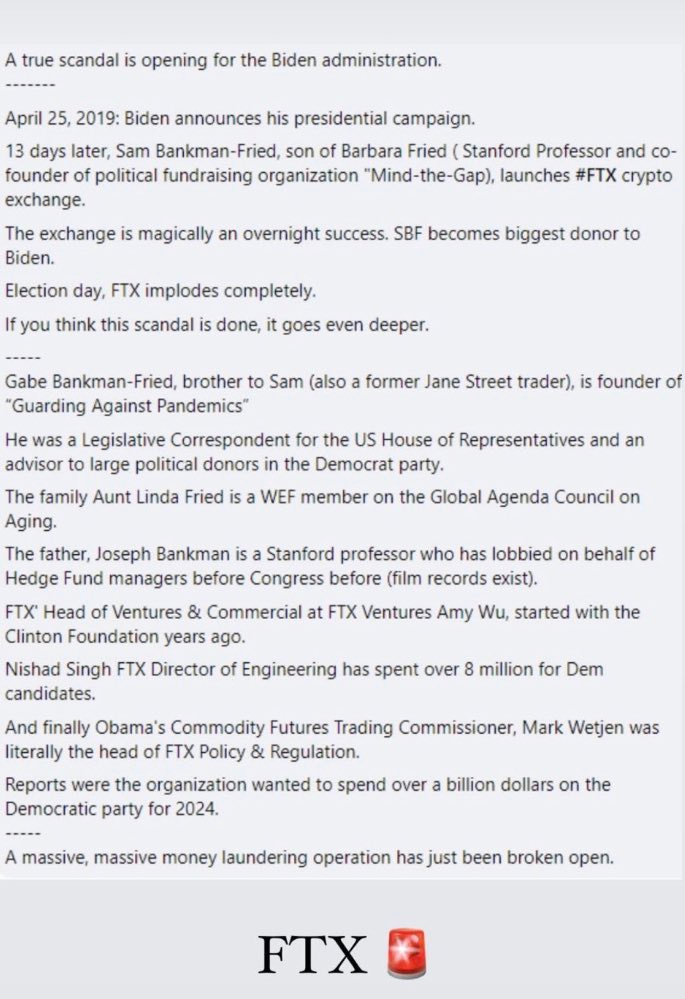

For example, you may have heard about the bankruptcy of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, but did you hear about its links to the Biden administration?

Shall we dig deeper? It’d be the right thing to do. But what would it do to our politics? Would it make our politics more virtuous, or, like Brazil, would it make our politics more chaotic? Perhaps unchecked corruption is the cost of political stability, but how much is too much? There are no good answers to these questions.

If democracy is under assault in America, it’s really under assault in Brazil:

Just days before the runoffs, the TSE justices passed a resolution giving them “special powers” to “combat fake news” in the name of “saving democracy.” No wonder a sizeable portion of the populace is now skeptical of the status quo and doubts the ability of the officials to uphold fairness, equality, and transparency. As for democracy, it must be really at risk these days, judging from how this nonsense is being repeated everywhere.

Of course, that’s BS, an inversion. Censorship, oppression, and lack of transparency are the real threats to democracy.

Last night, this happened:

I can’t imagine the Regime not taking additional steps and a more active role in “fortifying” the 2024 elections. Neither side trusts elections any more than the other, which leads me to fear the ‘24 elections will be the most chaotic this country has seen, at least in our lifetimes. I’m bearish on Trump’s prospects for ‘24, but his victory would be devastating for the Left. Likewise, Biden’s re-election or some other Democratic candidate’s ascendancy would not be taken well by the Right, which has no other avenue beyond winning elections to impact governance. I contend we’re not going to see a civil war or revolution break out over this, which is why what’s going on in Brazil right now is important to pay attention to. What’s happening there is probably the best-case scenario of how 2024 might look in the U.S.

It’s also important to remind everyone the stakes might be high for America, but they’re still not as high as they could be. The U.S. is still in a very stable state and I’m beyond tired of hearing people talk as if we were Russia in 1917 or the Soviet Union in 1991. The reason why Brazil’s elections are so fraught go beyond mere partisanship:

In a country that just thirty years ago was putting up a fight to regain democracy, the fact that several protests occurred in front of regional commands with large crowds of protesters demanding the military to intervene and interfere is alarming, to say the least.

But it has an explanation: every communist and socialist dictatorship in Latin America is a close ally of Lula and his Labor Party. That includes Nicarágua’s Daniel Ortega, Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela, Miguel Diáz-Canel of Cuba, and Argentina’s Alberto Fernández, who were the first to call and congratulate him on his victory (Joe Biden also hurried to call Lula. So, my fellow Americans, make of that what you will).

These countries, despite being at various phases and different levels, are all experiencing social unrest, soaring inflation, and growing poverty as a result of disastrous (i.e., unconventional and populist) economic and social policies.

So is Brazil – and that’s precisely why these kinds of policies that Lula and his cohorts are currently mulling raise so much concern, even among some of his supporters. Proposals like creating ten additional ministry cabinets, raising the debt and budget ceilings, printing more money, and many others which have been tried in the past and have failed spectacularly.

And lastly, it’s not exactly good advertising for anyone, much less a president over whom a number of suspicions and legal accusations hang like a heavy sword, to see ample footage of criminals and inmates celebrating Lula’s victory in penitentiaries and drug dens across the nation.

Not that a cynical sociopath like him gives a damn about any of that, particularly now that he’s back in charge. But to most other honest citizens and me, this is just another worrying indication.

Calls for military intervention in the wake of the 2020 election aside, the U.S. has never been a dictatorship, military or otherwise. The likelihood our armed forces would play a role in the electoral process is next to nil and, given the military’s loyalty to the Regime, their involvement in elections is something to be avoided at all costs.

Brazil, like most of Latin America, is desperately trying to avoid falling back into the clutches of authoritarianism, which is why so much rides on these elections. I can’t imagine the U.S. ever not being a democracy, but as we become more divided, Congress becomes more impotent, and more power and greater expectations vested into the presidency, the U.S. can and likely will take on a more authoritarian-like character. Culturally, we’ve already entered the early stages of “soft” totalitarianism through “cancel culture,” constant surveillance and tracking, and increasingly heavy-handed political correctness. Politics has already become a zero-sum game in America and when that happens, there must be a hands-down winner. I’m not sure how elections alone can decide that, however, nor settle the increasing cultural and political differences that are forming into two distinct proto-national identities.

Ommar relates a point similar to what he made in his prior piece about not giving in to “doomerism:”

I’ve never been into doomsday porn or negativism, not even at the height of my obsession with preparation. Who knows, maybe it’s my temperament – or maybe it has something to do with the fact that I was born during a military dictatorship, lived in a developing country, and am still alive. I’ve been consciously attempting to steer clear of apocalyptic discourse. I strongly encourage you to do, too.

I mean, no doubt profound changes are coming, and things will get much harder. But I choose to remain positive. This isn’t the end of times, just another crisis.

Even pivotal occurrences like elections and government changes are not always only negative or positive. The majority of the time, real life continues to be fairly normal outside the echo chambers of social and mainstream media. Depending on where you are, it can be harder or easier, but there won’t be mayhem. Not yet. It is as it is.

However, I won’t quit being realistic. The authoritarian forces that control politics and the mood/mentality of the populace in every other western country are also at work in Brazil. While I have no influence over that, I can continue to prepare, but I choose to do so without giving in to anxiety, fear, or political sway. [bold mine]

I implore you: listen to these people! They’ve lived it, you haven’t! I don’t care how many countries you’ve visited, how many military deployments you’ve been on, nothing compares living in a land where dictators once lorded over you and your parents, where corruption is so rampant, it’s not even newsworthy, or the economy actually collapsed and prices went up not by 1%, but by 10% each month, all while goods and services remain scarce! I say this not to downplay our troubles or gaslight anyone - those who do are part of the problem and deserve to be regarded with contempt - but instead to get you all to keep things in perspective. Unlike Brazil, we’re not dealing with a storm, we’re trying to steer clear of it. It’s just that our ship is being helmed by captains who refuse to change course.

I can’t point out how ironic it is that it’s Americans who’ve never lived through civil war, collapse, hyperinflation, etc., who seem so convinced it’s not only going to happen, but it’s happening any moment! They take it so personally when you so much as suggest they calm down and take a step back, because they’ve invested so much of their emotions and, in some cases, money, into these narratives. Please bro, just believe me, bro. Bro, we’re collapsing and we’re going to become like Bosnia in the 1990s, bro. Please bro, buy my book so you can understand, bro! It should be obvious what’s going on here.

Prepare, but do so as to not live in fear. Don’t spend your days contemplating the deaths of millions in this country, unless that’s something you aspire to see, which would indicate your concerns are much closer to your heart.

One last thing: If Brazil, a country in far worse shape than the U.S., can weather one political crisis after another, why couldn’t the U.S.? It may not be emotionally satisfying, but there’s no greater gift in this world than to just keep on living. At the end of the day, that’s all we want, isn’t it?

Max Remington is a defense, military, and foreign policy writer. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentLoyalist.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

Worth noting Super Bowl LV was the lowest-rated Super Bowl since 2006, though some of this may be attributable to digital streaming.

Historically, a landslide is considered to have occurred when a candidate wins 80% or more of the electoral vote. This would’ve meant winning around 430 electoral votes, 126 more than Trump won in 2016 and 124 more than Biden did in 2020.