The High Cost Of No Entry Fee

Inclusiveness works best as a sentiment, but not as a practice.

I often discuss the topic of social trust and how the abundance or lack thereof is as good an indicator as any of the state of society. But it’s definitely not the whole story because while high-trust certainly makes for a better society, it’s not necessarily a required component for societal function, either. Most of the world is low-trust, after all. What really matters is how societies manage relations and trust happens to be just one component among many.

Social scientist Rob Henderson made an interesting observation about Costco Wholesale Corporation recently:

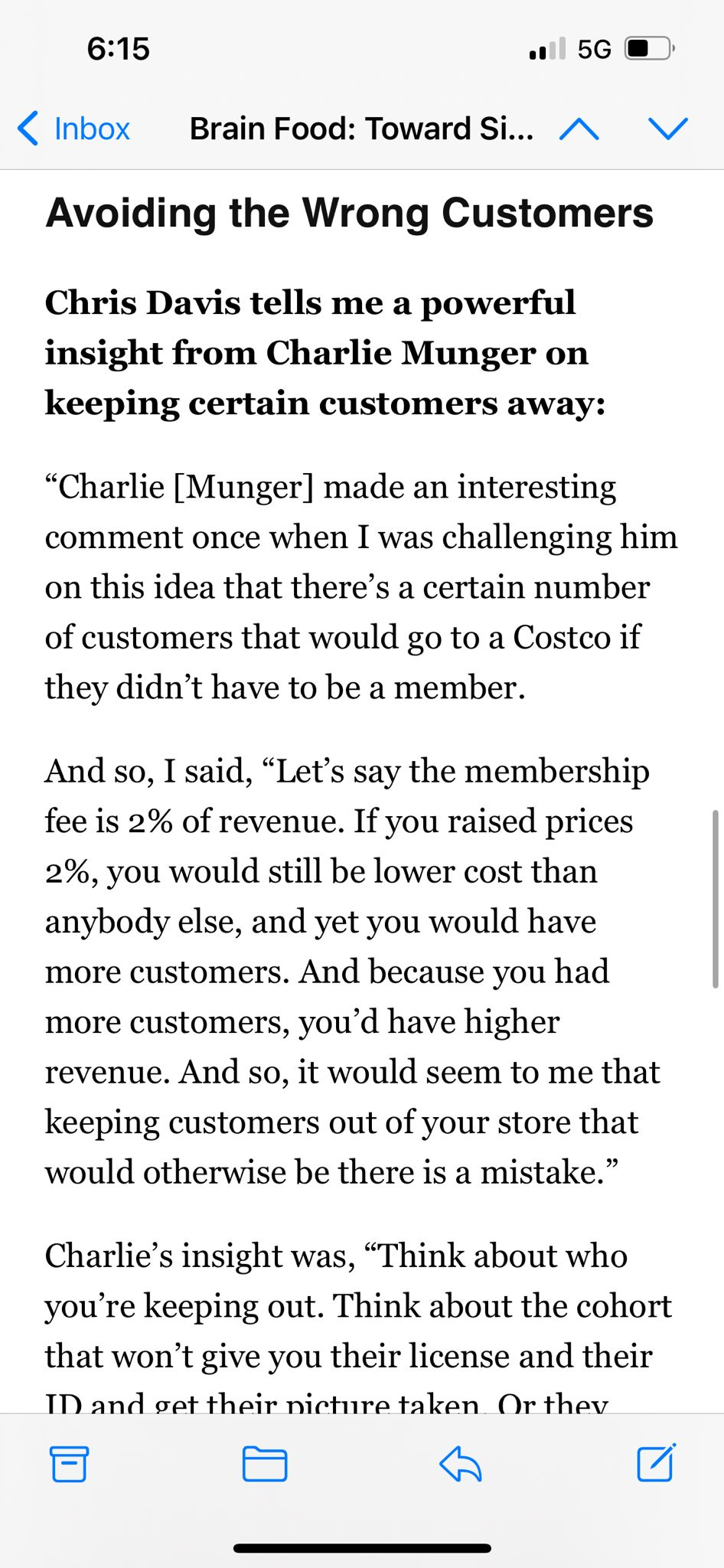

Here’s the argument Charlie Munger made:

And:

Munger is saying that by being exclusive, rather than inclusive, Costco saves itself and its clientele lots of trouble by simply not inviting in troublesome people in the first place. That’s not to say Costco is a trouble-free place - nowhere is - but one would need to be obtuse to think that Costco deals with shoplifting and anti-social behavior with anything close to the frequency of Walmart or any other retailer open to all.

We live in a time when “inclusiveness” trumps all other considerations, so the fact that something like Costco is able to maintain its business model is kind of intriguing. Nobody wants to say it, but things aren’t made better, not necessarily, by making it open to all. Inclusiveness works best as a sentiment, but not as a practice.

What do I mean? Ask yourself: do you enjoy paying a membership fee for anything? I’d wager that most of you would say, “no.” It’s a perfectly rational response. Then ask yourself: do you enjoy the benefits of paying the membership fee? Hopefully, the answer is “yes,” because otherwise, what are you paying for, exactly? Finally, ask yourself: what would happen if that membership went away? Would those benefits get better or worse as a consequence?

Apply those questions to Costco. What would happen if Costco did away with membership fees, while raising prices by two percent? In all likelihood, Costco would see higher sales. It’d be good for the company, but at what impact to the customer? If there’s any single criticism members have of Costco, it’s how busy it can get. Now imagine how much busier it’d become if membership was eliminated. Would it still be worth the trouble, then?

You’d also have a lot more different types of people showing up than you did before, people who probably don’t belong in civil society, period. These people would deteriorate the quality of the shopping experience at Costco, which is already uncomfortable due to the amount of consumer traffic each store is subjected to daily. Over time, Costco would end up enduring the same problems seen in other retailers - theft, smash-and-grabs, pranksters, violence, etc. Again, Costco isn’t totally immune to problems, but only the intellectually dishonest believe what Costco has to deal with is the same as what Walmart or Target must deal with.

If anyone needs convincing, consider that in 2022, Walmart suffered an estimated $6.1 billion in losses due to theft. This may seem like a drop in the bucket compared to the revenue the company enjoys annually, but theft always impacts individual stores the most, even if it doesn’t hurt the business as a whole. Then there’s also the problems Walmart has keeping the disorderliness of American life away from inside its stores. Not to mention net income itself is a small percentage of revenue.

By comparison, Costco has a much lower rate of theft, a big contributor to its success. It’s just not something that affects its stores the way it affects stores of other retailers. Obviously, it’s not easy stealing goods from Costco due to the size and quantities of the products sold. But one would have to be a fool to think the membership-based model has nothing to do with it, either. Think: a Costco membership costs $60 per year. Why would someone pay a membership fee that high just to engage in thievery? People do crazy, stupid things all the time, but don’t outsmart your common sense here. The day that Costco suffers rates of theft similar to that of Walmart would be indicative of a general breakdown of order in American society, not an indictment against the business model.

The higher revenue generated by a larger customer base might be worthwhile, it may not. The stores will be much busier, but there always exist self-imposed limits. Stores are only so big and can only handle so much throughput, after all. In other words, there’s a limit to how busy you can actually be. This works the other way too, however. If the business can only handle so many customers, then you eventually run into the point of diminishing returns, where the higher revenue doesn’t justify the stresses created by more patrons. Sure, Costco can expand, establish more stores and hire additional employees, but this requires capital. Operating additional stores is costly, so there would need to be trade-offs made: raise prices even higher, reduce staffing per store, carry fewer products, etc. I haven’t said a word about paying for private security, which would become an inevitable requirement if memberships were no longer required.

It need not be said explicitly - the numbers speak for themselves - but Costco’s business model is both profitable and sustainable because it minimizes the riff-raff the company has to deal with. It attracts only those able and willing to pay the membership fees and the cost of Costco’s goods and services. Think about the last time you saw delinquents or vagrants at Costco versus the last time you saw them at Walmart or Target. You see the same phenomenon at any other business with restrictive entry barriers. There’s just no denying that the more exclusive something is, the better the product, service, or experience. It’s very possible to satisfy a focused group of people, but much harder to satisfy the masses, and many among the masses aren’t invested in your success anyway, especially if they have no skin in the game.

Why am I talking about this? What does Costco, any of this, have to do with prepping, civil war, or collapse? A lot, actually.

Misery Loves Company

There’s an increasingly prevalent saying in right-wing circles: The goal of American life is to make enough money to escape the consequences of the Civil Rights Act. To most Americans, that comes off as deeply racist. But put aside your feelings on race for a moment and consider the fact that the Civil Rights Act did, in fact, undermine the concept of freedom of association in America. It created an environment where any racial disparity or “imbalance” was attributed to racism and, therefore, illegal.

It’s not necessarily a hard and fast rule, of course. Racial imbalances exist everywhere in life and most of the time, it goes un-scrutinized. When it is brought to the attention of those in positions of power and influence, however, it becomes a problem. Public pressure is built in order to force a more equitable outcome, the assumption being that any racial discrepancy undeniably must be the product of racism.

As this isn’t a cultural blog, I’m not going to get too deep into the weeds of this debate. Most of you are old enough and well-informed enough to be aware such a debate exists and what it’s contours are. The point I’m making is that we live in a society where it’s becoming more and more difficult to distance yourself from circumstances you and your loved ones would prefer not to be a part of. In a supposedly free society, freedom of association is as important, maybe more important, than freedom of speech. We don’t always practice the latter, but we definitely practice the former on a daily basis. None of us are truly free if we cannot choose for ourselves whom we spend our free time with (remember that this is exactly the argument used by the LGBTQ+ community in their never-ending campaign for more rights).

Back in April, a community in Baton Rouge, Louisiana voted to leave the city, establishing their own city called “St. George.” Years of high crime and poor schools prompted the secession, which itself took years to implement, with residents of St. George no longer willing to bankroll dysfunctional, failing communities with their tax dollars. It’s a perfectly rational choice, but the reaction was predictable. “Racism” was cited as the primary motivating factor, as if those who aren’t racist would want to see their tax dollars spent on poor governance, disorder, violence, and sending their children to schools no better than a state asylum. There’s also the irony in the anti-secessionists, who are mostly Black but also include left-wing Whites, demanding to have access to the resources of supposedly racist Whites, but as I explain ad nauseum, none of this is supposed to make sense.

You see this elsewhere throughout the world. In South Africa, there exists the all-White community of Orania, which is a thriving oasis in a country otherwise in a state of perpetual collapse. While the post-Apartheid South African government has mostly left Orania alone, it’s recently come under increasing fire as the country’s endless crisis intensifies. After all, if the entire country, especially when it’s comprised mostly of Blacks, is in misery, they cannot afford to have a single nice place in the country, especially it’s to the benefit for Whites. The ideology that animates most of the world is that any racial disparity must be corrected by forcing better-off groups to share their resources and spaces with aggrieved groups, even if the end result is misery for all.

The biggest reason I see a civil war as becoming increasingly likely in the U.S. is for the same reason I saw it as unlikely just a few years ago. America is a massive country and there’s plenty of space to run to in order to escape chaos, disorder, and violence. Unfortunately, the number of those places are dwindling in number. As they do so, the places that do remain as refuges from the storm will increasingly come under fire. Nobody wants to admit it, but armed conflict, civil war specifically, is often the end result of incompatible peoples being forced to share living spaces with one another.

It’s unfashionable to say. But having people of different races and cultures live with each other has never been easy. Humans are biological creatures and biological creatures are tribalistic. Over time, people can be influenced into expanding that tribe, but everything runs into limits. Forget race for a moment; we accept, for the most part, that people of different classes will inevitably live in different communities. Throw race into the mix, however, and such an arrangement becomes totally unacceptable in contemporary culture.

Even if someone honestly believes racism is the biggest problem plaguing America today, forcing people to live together only makes sense if the objective is to force one group to accommodate or capitulate to another. We don’t co-exist as much as we live by a dominant social structure. We like to think that better ideas always prevail, but even when they do, it’s often through violence that they do. Everyone has a different take on what’s a good idea and what’s not.

Samuel Huntington once said:

The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion […] but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact; non-Westerners never do.

This principle works the other way, too. When bad ideas prevail, it’s also through violence. This isn’t the same as saying bad ideas can be forced to work; no bad idea survives first contact with reality. But why do bad ideas get turned into policy or perpetually enforced despite the results? The question answers itself.

An essay from the September 2022 issue of The Atlantic recently resurfaced, becoming a major topic of discussion. It argued that quiet was for wealthy Whites, while poor non-Whites (the author isn’t) should be allowed to make their neighborhoods as loud as they please. Never minding the fact that excessive noise is something few people really enjoy when they never asked for it yet are on the receiving end of it, I’m not sure the author realizes she effectively made an argument against forcing different people to share living spaces.

Decide for yourself, as she describes the impact of gentrification:

For generations, immigrants and racial minorities were relegated to the outer boroughs and city fringes. Far, but free. No one else much cared about what happened there. When I went to college, it was clear to me that I was a visitor in a foreign land, and I did my best to respect its customs. But now the foreigners had come to my shores, with no intention of leaving. And they were demanding that the rest of us change to make them more comfortable.

Ironically, I’d agree with her that when forcing people of different cultures, lifestyles, and value systems to live with each other, one side needs to prevail outright over the other [bold mine]:

Attempts to regulate the sounds of the city (car horns, ice-cream-truck jingles) continued throughout the 20th century, but they took a turn for the personal in the ’90s. The city started going after boom boxes, car stereos, and nightclubs. These were certainly noisy, but were they nuisances? Not to the people who enjoyed them.

I wonder if she read any of this essay to herself before she submitted it for approval. Anyway, the message here is, “If we like it, what’s the problem?” The problem, of course, is that this clearly doesn’t promote civil coexistence. But this assumes civil coexistence was ever the goal. Those who feel aggrieved have no desire to come to any kind of rapprochment with those they feel are encroaching (in this case, on their right to be as loud as they want).

Going back to St. George, Louisiana, it’s years of this sort of thing which motivated residents for the establishment of a new city:

One last time, put aside your feelings on race, civil rights, whatever: how does wanting to separate yourself from this in any way unreasonable or even racist? Why should anyone tolerate this for their children? Finally, if racism is your concern, how does “White flight” exacerbate tensions if the presence of Whites is seen as the problem itself?

All this is just screaming into the void on my part. But as preppers, as Americans, we need to come to terms with the fact that we are increasingly being forced to endure misery as part of a nihilistic attempt to destroy the country, while looting it for what it’s worth in the process.

It’s Your Patriotic Duty To Endure Misery

What are we to do about this? The short answer: as long as we remain an anarcho-tyranny, as long as diversity, equity, and inclusion remain our most sacrosanct of values, as long as the Civil Rights Era of our history remains our most defining national moment, not much. Free association isn’t legally protected; it’s effectively discouraged, and the response to walking away is for those who can’t leave well enough alone to follow.

There’s one exception to rule: the Costco model. We still live in a society where it’s possible to exclude people on the basis of their willingness and ability to pay for a better life, a better experience. As conditions deteriorate inside the country, I’d expect more places to begin not only charging entry fees, but also charging higher prices in an attempt to build an invisible barrier alongside visible barriers between them and a society crumbling around it.

It’s probably the most acute signs of Thirdworldization in the U.S. - having to spend more money just to enjoy the benefits of civil society. Go to any low-trust society with high crime rates and disorder anywhere on the planet and you’ll see that living in peace, harmony, and prosperity comes at a high cost. In the U.S. and throughout the West, we take things as entitlements. But these less-developed places may be more indicative of reality: you need to pay a premium for nice things. We can either pay for them ourselves, or we can pay for them as a society. Guess what choice we’ve made?

Making enough money to escape the consequences of the decision to unravel civilization in the name of diversity, equity, and inclusion and civil rights is the only way forward for now. But not only are the nice places running out, they’re also becoming crowded, prices are getting higher, and the Regime is finding ways to make exclusivity impossible to practice. Imagining that America as Costco, what happens when management decides memberships are no longer required? What happens when spending more for the better life is no longer an option?

It’s an unlikely scenario. The way things are going, however, it’s not too far-fetched, either.

Ready To Pay More?

What do you think? Are you a Costco member? Do you think the membership is worth the benefits? Or do you think Costco should do away with them? What would be the consequences? What steps, if any, have you taken to get away from the chaos and disorder that now defines American life? Have you found your happy place? Or are you finding that misery follows you wherever you go?

It’s time to talk.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

Ironically, I came across a story where the only Costco in NYC is dealing with a serious shoplifting problem, likely the only Costco to do so. Figures that it's NYC.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_10mUjGD7A

I have a confession to make: I am a Costco freeloader.

Years ago when I was working in Honolulu, I earned the minimum wage and couldn’t justify spending an extra $60 per year. However, my roommate had a membership, so we researched ways to allow me in as a guest. Turns out, you can add somebody to your standard membership provided you live in the same household, so that’s what we did. No extra fee, and they issued me a card under my roommate’s account number once I proved my address.

I haven’t spoken to this guy in seven years, and still I’ve never had to pay the fee, lol.

The membership is absolutely worth the benefits, even when you don’t get it for free. I think it helps too that Costco’s clientele is more business savvy than the average consumer: they run small businesses, they have large families, they’re more likely to live in the suburbs, to have more capital, etc. Not to mention the membership model incentivizes people to do all of their shopping under one roof, so I imagine you get a higher proportion of big transactions—televisions, Christmas trees, cruise ship packages, etc.—rather than a bunch of more modest transactions.

I have zero complaints about how Costco is run. I’m amazed to this day that the hot dog and drink combo remains at $1.50 (unchanged since the 1980’s!) and the rotisserie chicken is still only $5, even in Hawaii. They absolutely lose money on those items, yet it’s part of their cultural identity to keep them unchanged.

I never really thought of Costco’s membership model as having benefits re: shoplifting prevention, but I guess it’s not surprising that you can get better service when you put up a barrier to keep out the riff raff. I’m still not sure how the receipt checker folks at the exits are trained, because I’ve never once seen them closely inspect a cart or detain someone—they just count the number of items in the cart to see that it matches what’s printed on the receipt—but I imagine they look closely at electronics and other expensive hardware.

There must a psychological component to ponying up the membership fee: it reinforces that shopping at Costco is something of a privilege that’s worth preserving through good behavior. I guess the same can be said about gated communities or formal dress codes, but I’m not sure how well the analogy holds…