Final Destination, Part I

So, what does “the end” and beyond hold in store for America?

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This essay is the first of a two-parter. I had to split it once I realized how long it was getting. I’ll be releasing Part Two tomorrow. I’ll also be out on a much-needed vacation later this week into the next. My plan was to release at least one additional piece beyond tomorrow’s before departing for rest & relaxation, but circumstances may change that plan. As such, please don’t be surprised if you don’t hear from me for the next two weeks or so. I’ll be back to posting sooner than you know it!

Some of you might’ve surmised that I’m a big podcast guy. If you haven’t… I’m a big podcast guy.

Though it’s not one of my usuals, the podcast Subverse with Alex Kaschuta is one I tune into occasionally. In the latest episode, Kaschuta interviews Adam Van Buskirk about the topic of collapse, complex systems, and prospects for revolution. Of course, I had to listen to this one and wasn’t disappointed. I hope you’ll all give it a listen, as both Buskirk and Kaschuta had valuable things to say about matters relevant to what we discuss here in this space.

On the matter of collapse, Buskirk notes how ironic it is that the one scenario the “collapsitarians” (my word, not his) rarely consider is the prospect nuclear war. Yet Buskirk notes that this is precisely the event that’d bring about the cataclysmic collapse so many are convinced is on the horizon. Much of what we read in prepper-survivalist literature, TEOTWAWKI (The End Of The World As We Know It), a lot of it would be the consequence of a truly world-shattering event like nuclear war, foreign invasion by a bona fide military power, or an asteroid striking Earth, as Buskirk mentioned. Without these kinds of events capable of bringing literally everything to a screeching halt, a cataclysmic collapse isn’t going to happen so easily.

Related to collapse is the concept of “complex systems.” Many are convinced collapse is going to happen soon because we’re reaching some sort of self-imposed limit on the functionality of the complex systems that run modern society. It’s an argument you hear frequently on the dissident right, but intelligent as it sounds, it’s based on shallow reasoning. When you’re convinced society is undergoing collapse, you become predisposed to seeing every last failure as evidence of it. Something as simple as a ship colliding with a bridge, which is hardly an unprecedented event, is considered indicative of collapse, as opposed to something that just unfortunately happens from time to time, the same way car accidents are a risk inherent in driving.

What’s really going on, however, is that things are more stable than appreciated in large because our society is run by complex systems. Buskirk explains that while complex systems require more effort and expertise to operate, they also have built-in resilience and redundancy. This explains how, for example, the world didn’t suffer from the predicted famine following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, nor did the recent situation in the Red Sea lead to skyrocketing inflation. The thing about simplicity is that it’s often accompanied by single points of failure. Whatever the downsides of complex systems, they offer multiple points of failure, along with adaptability, making it more difficult for the entire system to come crashing down absent a civilizational threat like nuclear war or an asteroid impact. The fact that collapsitarians rarely point to either event type suggests it’s not so much that they believe it’s all about to come crashing down, but they want to be the ones who benefit if it were to happen. Hence, their bias for civil war, revolution, secession, etc.

Buskirk and Kaschuta both agree that much of the discourse concerning collapse or revolution is rooted in general discontent rather than real-world conditions. This isn’t to say things are fine - they’re far from it - but that society has reached a level of robustness that trends towards stability more than chaos. This doesn’t mean collapse is no longer possible, but that it’s just takes more than it did in the past to trigger it.

As I argued recently, fragile structures don’t remain standing for long. You can only scream “We’re going to collapse!” so many times before you become the boy who cried “wolf.” The law of averages states that bad outcomes eventually result over a long enough timeline, so anyone who wants to argue that a collapse will occur “soon” will need to put forth a more convincing argument, rather than just pointing to the vulnerabilities of complex systems. Otherwise, they’re just relying on averages eventually proving them correct in the long run, which ultimately proves nothing, besides the fact everything has its day in the sun.

As far as revolution goes, Buskirk points out that much of the revolutionary fervor today comes from the demographic historically least likely to participate in a revolution. So much of the discontent is most openly expressed by older White males of the Boomer and ‘X’ generations, who are among the most radicalized and enraged enough to seek revolt. But though they may be heavily armed, they lack physicality and have invested too much into the system to throw caution to the window and completely upend it. There’s a reason why property-owners are often victims, not perpetrators, of revolution. Ironically, those who stand most in opposition to the status quo in today’s America also possess the least incentive to overthrow it. Perhaps nobody really does.

As I’ve been arguing frequently as of late, until access to food, fuel, and other essentials like medical care become truly problematic, the risk of revolution or civil war remains low. That’s when the Internet will no longer serve as a sufficient release valve for all that pent-up anger. The same thing applies to all the angry young men out there. Buskirk notes that in past revolutions, life was so physically uncomfortable, that there wasn’t much to lose by taking part in a violent upheaval. Either way, even if lots of angry young men alone were enough to trigger a revolt, it would’ve happened by now. How much anger do you need, anyway?

The free version of the podcast episode linked to above is a shorter version of the complete conversation. It ends just as they get into the topic of the so-called “competency crisis,” which Kaschuta seemed to be leaning towards seeing it as mostly overblown. I made the same argument back in March in response to the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse in Baltimore after it was struck by a container ship leaving port. Kaschuta adds that she believes the bigger problem may be that these civilization-sustaining jobs are the ones young people are “checked out” of, to use her term. Unfortunately, we never get to hear Buskirk’s response in the short-term talk - listeners need to subscribe to the Subversive Patreon to hear the long-form talk, which includes a discussion on “Red Caesar” and the prospect of authoritarianism coming to the U.S.

The conversation was highly intriguing even in its short-form and it’s a perfect opener for the meat of what I wanted to talk about in this entry. The title of my blog, of course, is We’re Not At The End, But You Can See It From Here. I’ve spent less of my time talking about what that “end” is because, who really knows? I often remark that making long-term predictions is easier than making short-term predictions, but it’s also a matter of a broken clock being right twice a day, as Buskirk put it during the interview. It’s much tougher making short-term predictions, yet these shorter-term predictions matter far more due to their proximity to our own time. This is the built-in irony of futurism.

Sometimes, however, talking about the long-term future is useful, because, as many of you will attest, the years go by quickly. So, what does “the end” and beyond hold in store for America?

I think it’s going to be at least another generation (as in the babies born this year will need to graduate from high school) before the picture really starts coming into focus. For now, speculation runs rampant, but when it comes to the more educated guesses, you hear terms like “Brazilification,” “South Africanization,” or “Third Worldization.”

Each of these three terms are loaded and it’d take an entire essay to sufficiently unpack each of them. For now, it suffices to say they each suggest the United States and the West as a whole will become a more chaotic, unequal, and violent society with a lower standard of living, coming to resemble countries like Brazil and South Africa - not quite the dredges of the planet, but far from what we once were during the halcyon days. Perhaps the First World comes to resemble today’s Second World.

Like with so many things, I think it’s easy to get carried away with these comparisons. Things are obviously changing however, and for the worse, so we do need to have some clue as to what the new world will look like in order to be prepared. While I sincerely doubt the U.S. will come to look like Brazil or South Africa in the next 20 years, I think we’ll definitely come to take on characteristics of these countries in small ways, if not in their entirety.

For now, let’s focus on South Africa.

The Forever Collapse

, who has an excellent Substack of his own, recently discussed South Africa. He quoted commentator Dan Roodt, who said that his country is a “canary in the coal mine” for the West. Personally, I believe there exist multiple canaries in the coal mine for the West, but South Africa definitely serves as a worst-case example. For a number of reasons, a South Africa-like outcome is quite unlikely in the U.S., demographics not being the least of them. Still, it’s something which could happen in parts of the country and the implausibility of the scenario overall says something about what America’s ultimate fate actually is.There’s no question South Africa is a failing country. However, it’s been failing for a very long time. Apartheid ended in 1994 and it hasn’t recovered from the consequential turmoil since. Moral arguments against apartheid aside, nobody can say the country is better off today than it was when the old order came to an end.

Here’s Stark’s bottom line [bold mine]:

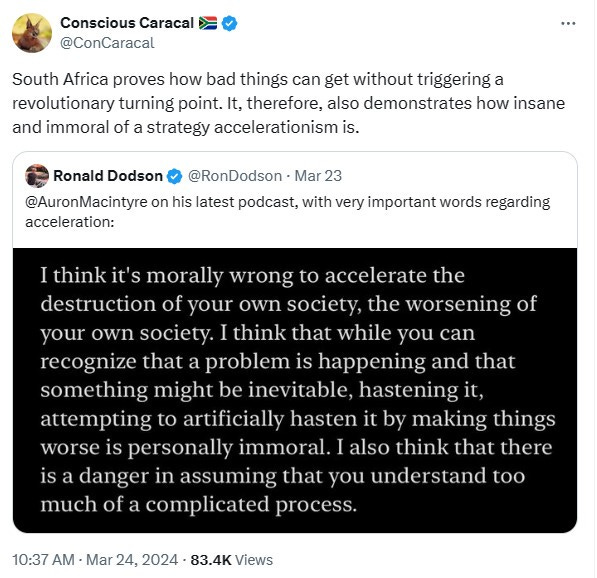

South Africa is experiencing a slow-motion collapse and has taken much longer to collapse than many anticipated. South Africa is an 80% Black country that is very “Woke” by non-Western standards, so it should have long since collapsed by all metrics, according to Western right-wingers but somehow it hasn't. If South Africa does not collapse, it totally discredits accelerationism and shows how long the American system can be sustained with a managed decline. South Africa serves as a grim reminder about how dysfunctional and shitty a State can be while still existing and exerting power over the populace.

And:

The dissident right pontificates about whether America’s future will be like Brazil, South Africa, or Trudeau’s technocratic Canada. I foresee pockets of America that are like Brazil or South Africa, hypercompetitive company towns dominated by Asian and Indian immigrant managerial strivers, middle class Whites continuing to get squeezed out from both the top and the bottom, rural White conservatives becoming more tribal and totally isolated from major institutions, and the White upper class gatekeeping non-White strivers while sequestering certain zones away for themselves.

I’ve spoken on it before, but there’s a tendency in the prepper-survivalist community or anyone who wants to chime in one the coming collapse of the U.S. to default to the worst-case scenario. Why they have such a hard time staying in reality is beyond the scope of this post, but here’s the thing: if a country like South Africa, in far worse shape than the U.S. and the West, can keep going on like this without completely falling apart, there’s nothing to suggest a worse fate awaits the former in the next 30-some-odd years. To say otherwise is mostly cope, a desire for our enemies to receive righteous justice and for the slate to be wiped clean for a brand-new civilization to rise from the ashes. I can understand the sentiment, but again, we need to live in reality, not inside our own heads.

Another thought that populates the heads of many in the prepper-survivalist and dissident right communities in the prospect of mass racial violence, even genocide. Certainly, there’s no way to talk about South Africa without talking about race, given its past. There definitely does exist high levels of racial violence in the country, perpetrated by the majority Blacks against the minority Whites, specifically those living in rural areas. The South African government denies any racial element to these crimes, but I think we can agree there exists strong incentives to downplay such motivations.

However, Stark explains that while racial violence is a real problem in South Africa, the risk of racial genocide is not only overblown, it’s often outside observers who seem most committed to this narrative, not South Africans themselves:

American right-wingers hyperbolically use the term White genocide, to describe South Africa, as well as the situation in America. However, the mainstream human rights organization, Genocide Watch, places South Africa in the 6th Stage of Genocide, which is polarization. This is due to attacks on White farmers but also xenophobic attacks on African immigrants, with the perpetrators being South African police and the leftist Black Nationalist, Economic Freedom Fighters. Farm attacks have surged after the EFF’s Julius Malema chanted “Kill the Boer.” The next stage for genocide is preparation.

However, a systematic genocide, like the Rwandan Genocide, is not likely in South Africa, and I have noticed this narrative more from the online American right than from South Africans. This is because, unlike Rwanda with a clear Hutu majority, South Africa’s Black population is divided up into many ethnic groups which do not trust nor care much for each other. South Africa’s geography and population are so dispersed, with Whites concentrating in the Cape region. The Cape’s dominant mixed-race Coloured population, would likely ally with Whites if there was an ethnic sectarian conflict. However, Whites in urbanized parts of Gauteng (Johannesburg and Pretoria), as well as Durban would be vulnerable in a collapse scenario.

Explained another way, the risk is greatest for Whites who are isolated, while more diffuse for Whites as a whole. How does this relate to the U.S.? Unlike South Africa, the U.S. and Europe as a whole remains majority White. While Blacks are overwhelmingly responsible for interracial crimes, this doesn’t necessarily translate to large-scale racial violence or ethnic cleansing. I’ve noticed that while anti-White sentiment is high in the Black community, it’s just as high among White leftists, who harbor strong out-group preference and weak in-group preference, making them unique among all demographics.

Given the preponderance of White leftists in positions of power and influence, I’d argue there exists a strong incentive to not allow racial violence to get out of control, since not only would it eventually spill over onto them, they’d be the ones held responsible for it. Anti-White sentiment is arguably what unites the Left above all else, but White leftists do have skin in the game, to say nothing of the fact the numbers don’t work out in your favor if you’re 13% of the population, as Blacks are.

If South Africa is an imperfect model, others that have been touted, like Lebanon or post-communist Yugoslavia, are far more so. Macabre as it sounds to say, genocide requires skill. It’s not just a matter of unleashing tremendous violence on a population. You can certainly rack up tremendous body counts through large-scale violence in general, but this isn’t the same as genocide. Even if this is just a matter of semantics, the point is that the current strategy by the Regime to control the populace is working too well to demand a change in approach.

Stark explains [bold mine]:

South Africa has not really had a full-blown ethnic sectarian conflict, and even the 2021 Durban riots, proved that revolutionary forces just don’t have the competency to carry out a genocide. For a systematic genocide to occur, South Africa’s main Black ethnic groups would have to unite under one anti-White banner and be well organized, which is not to say impossible but not a likely scenario. What is likely is an increase in racially motivated violent crime, rioting and looting, and anarcho-tyranny, with the State refusing to prosecute anti-White violence. Basically, South Africa is non-stop, low-intensity civil unrest and high crime but they never get big events like civil wars or revolutions.

Sounds like we’re kind of already there, doesn’t it? This is what’s most likely for the U.S. and the West going forward: an intensification of existing trends. As Adam Van Buskirk said during the podcast, maybe “the moment” like a civil war or revolution never comes, at least not in our lifetimes. Instead, we transition into a state of non-stop, low-intensity conflict and high crime. To the extent a moment ever comes, it’ll be something like an economic or political collapse or a mini-civil war/revolution. But nothing that permanently alters the trajectory of the country.

The other intriguing thing about South Africa is that it remains a developed world country in many ways, despite an increasingly Third World exterior:

South Africa has bubbles where well-off Whites live that are basically First World on a small scale. South Africa’s upper middle class and wealthy have a high quality of life, despite the dangers and potential of becoming targets of the regime. However, these bubbles are maintained by extensive private security and lots of servants. Not to mention White flight, such as from Gauteng to the Western Cape serving as a safety valve.

While South Africa is overall dangerous, it has not gotten to a critical mass where most of the wealthy feel a dire need to get out. While South Africa lost about 11k millionaires over the past decade, South Africa has recently become a magnet for digital nomads from Europe and the US. Also, because real estate is so cheap while the South African Rand is weak, a lot of the wealthy are hesitant to downsize from a massive estate to something much more modest in say London, Sydney, Vancouver, or California.

South Africa remains one of the world’s top tourist destinations, certainly the top tourist destination in Africa, despite also being one of the most dangerous countries on the planet. It’s not unlike Mexico, also one of the world’s dangerous countries, while still being a major tourist draw, especially for Americans. The fact is, living in a country constantly embroiled in SHTF does have its benefits. Not sure that’s a deal I’d recommend from a prepping standpoint, though. For one, you’d need to possess large amounts of currency stronger than that of the country you’re living in.

Though nothing will ever meaningfully change until another major SHTF occurs making life more difficult than ever before, we shouldn’t assume that this will result in a broad-based political shift. The reality of South Africa hasn’t been enough for many, including Whites:

The dissident right assumes that once demographics reach a certain tipping point or the economy tanks, White normies will all get “red pilled” on race. However, even South Africa has a decent amount of Whites who are liberal on racial issues, with similar issues of upper-class Whites virtue signaling while throwing ordinary Whites under the bus. South Africa’s White elite made a deal with the new Black regime in order to retain their wealth, though this arrangement is unsustainable.

Once more, it sounds a lot like where America is today. I’m not an expert on how to change public political sentiment or even shift the Overton window, but I think I’m on-target in saying real-world conditions alone aren’t enough to change minds. What is and what people think ought to be are often at odds even in the worst of times, so it’d take something truly catastrophic, like a destructive war or total collapse, to change minds. Even then, it may only have the effect of entrenching existing views. Engineering public sentiment has never been a science.

As alluded to previously, a sustainable arrangement exists. It’s not desirable and it certainly won’t last forever, but we’re talking about what’s going to happen in the next 20 to 30 years, not what’s going to happen in the 22nd century:

While the dissident right assumes that a more non-White America will collapse, it is plausible for things to get much worse for middle class Whites while America’s imperial core is sustained. Even California has not collapsed, after hemorrhaging its White Middle Class, and gets by with a Latino working-class and increasingly Asian managerial class.

Finally:

However, America is far from collapse and I predict that foreigners will continue to buy US stocks, treasury bonds, and real estate as a hedge against instability. Basically, America will benefit from other nations’ chaos and demise. Even the hyperbole about civil war feels more like political theater rather than a serious threat to elite power, and Americans are too sedentary to rebel.

A fact that often gets lost in all the shouting is that even a U.S. that undergoes political or economic collapse, if not a total collapse, it’ll still be in better shape than most countries. There are dissenting views, but nobody seems able to come up with a substantive argument beyond their gut feeling. The direct First-to-Third World transition just doesn’t happen absent that civilization-threatening catastrophe like nuclear war, which even the most blackpilled spend little time considering. As SHTF expert Fabian Ommar once said, the First World will feel the loss more than the actual consequences of it. Our society being run by complex systems, it’ll manage to adapt to changing circumstances once again, just as humans eventually adapt to new realities. Anyone who says others isn’t being serious about the matter and is engaging in wishful thinking.

Take time and read Robert Stark’s entire essay on South Africa. Highly informative, you’ll walk away with a better understanding what South Africa’s problems really are. Though it may sound like he and I are attempting to whitepill readers on the future, this is hardly the case. Life will be objectively worse in America 20 to 30 years from now. My intent, and I think it’s Stark’s also, is to paint an accurate picture of the future, instead of wallowing in misery contemplating all sorts of worst-case outcomes. This is an unhealthy practice in your personal life; the same goes for prepping.

All said, South Africa didn’t become what it today overnight, either. Though it never achieved imperialism, it’s lifecycle was similar to that of any empire. In it’s late stages, it endured a generation-long inter-state armed conflict (so did its similar neighbor, Rhodesia, today Zimbabwe), tremendous internal instability in opposition to Apartheid, political upheaval, before the prevailing order finally collapsed 30 years ago.

Watch this video to get a glimpse of what South Africa was like in the last 14 years of Apartheid:

In some sense, yes, South Africa is in fact a canary in the coal mine for the West, not because of where it’s today, but where it’s been. What the country represents now is a society that has already seen one social order collapse and is now undergoing the collapse of another.

That means South Africa is ahead of our time, maybe too far in the prospective future to contemplate. It’s also a long geographic distance away from us. Let’s come back to our time and place to consider what just the next several years might have in store.

There Are Lies. Then There Are Dangerous Lies.

Over the weekend, President Joe Biden said the following at the commencement address at Morehouse College in Atlanta, a Historically Black College University (HBCU):

The implication is that Black men are being killed in America by their own country, but we’ll get to that in a minute. I think it’s criminal that Biden’s incendiary remarks don’t get anywhere near as much public scrutiny as Donald Trump’s mildest remarks received and that’s not because I like Trump more than Biden. I think the Trump-worship on the Right is troubling, but Biden is just something else.

As X mutual Frank DeScushin showed last year:

There’s more where that came from. Whether it’s Biden’s intent or not, such remarks sow division and hostility. How could it not? How does anyone with any common sense think such remarks would unite this country? Or is it intended to unite Blacks?

Whatever the case may be, there’s nothing innocent about what Biden said. I thought the lesson of the Trump presidency was that every last word uttered matters, but I suppose that doesn’t apply when a Regime man is in office. It’s even worse given what Biden said is based on a lie.

It isn’t “America” killing Black men in large numbers. It’s not White people or that of any other race, for that matter. It’s Blacks killing other Blacks. There’s no other explanation for murder rates of this magnitude, not even poverty:

2021 is the year the Black murder victimization rate peaked; it’s come down considerably since then. All fires eventually burn out. But if you watch the rest of the graph, the rate remains elevated far above that of the other races. For a variety of reasons, it’s more convenient to suggest someone else is killing Blacks than Blacks themselves.

But if Biden or anyone really wants to touch it, here’s what the reality of interracial crime in America is. The Regime’s narrative is, by comparison, a complete fabrication.

As you can see, interracial crime is far less prevalent than intraracial crime. Yet Blacks, despite being 12 to 14 percent of the population, murdered 130 percent more Whites than the reverse.

This is the graph which really blew my mind, however:

Note that as long ago as 1968, during the height of the Civil Rights Era, when America was an unbelievably racist country, over 160% more Whites were killed by Blacks than the reverse! It seems as though nothing has tangibly changed, only the way we interpret reality has changed.

One day, however, our interpretation of reality will change once more. It’ll need to, otherwise, we won’t survive, individually or as a society. How should we start re-thinking about this?

Last year, Richard Hanania said the following on the matter of interracial crime:

We can therefore ignore those who deny the reality of black crime. They’re either too stupid or dishonest to engage with. Among others on the left, there has been an acceptance of reality combined with pleas to simply frame the issue differently.

I know what Hanania’s trying to say, but we can’t ignore those who deny the reality of Black crime, not really. The people who do are the ones running the country - one of whom is the president. These people teach our youth, they’re your neighbors, co-workers, they’re everywhere. These people hold a monopoly on the discourse and are attempting to force an entire country to let down its guard. Ignoring them is dangerous.

More from Hanania:

When liberals talk about perspective here, what they usually mean is that the likelihood of a white person being victimized by a black person is small in an absolute sense, so why worry about it? It would be a fine argument, except that we are constantly told to obsess over the harms done by police shootings, white supremacist violence, and vigilantes falsely accusing innocent black men of crimes.

Now we’re getting into some prepper territory, specifically the issue of risk management. If you’ve been reading my work for some length, you know it’s something I speak on often and you also know that I believe most people are bad at risk management. The Left, however, weaponizes risk, which is the intersection between potential consequences and likelihood. As Hanania says, Whites, as well as people of other races, are told not to worry about being victimized by a Black person due to its low statistical likelihood, yet we must be up in arms over unarmed Blacks being shot by police, which is the furthest thing from an epidemic. We must be constantly on alert for White supremacist violence, even though, for most of us, “White supremacism” is listening to your uncle’s casual racism at Thanksgiving. We must avoid vigilantism at all costs, even though vigilantism is the logical outcome of increasing disorder. As I’ve said many times before, the people in charge don’t care about the data, they just want to be able to tell us when the data matters and when it doesn’t.

Hanania’s entire essay is worth reading in its entirety, but I’ll share this last bit:

There’s no “perspective” one can take from which a reasonable observer won’t find that inner city crime is a major problem, and something we should do our best to solve. The chart below shows the ten American cities of at least 100,000 people that have the highest murder rates, and how they compare to the most violent countries in the world. The murder rates for cities come from CBS, while the country data comes from the World Bank.

Did you see where South Africa lands on that chart? Unquestionably one of the most dangerous countries in the world, St. Louis, Baltimore, and Birmingham are all still statistically more dangerous than South Africa. But what do the four locations have in common? Demographics. All four are majority Black; the rest of the locations on the list are also majority or plurality Black, or in Latin America. At some point, the connection is impossible to deny.

Hanania’s analysis:

You might be saying that it’s unfair to compare cities to entire countries, since urban areas might have concentrated violence. Yet the most violent countries in the world tend to be small. For example, St Louis, which is number one in murder in the chart above, has 293,000 people. That’s a larger population than St Lucia (180,000) and St Vincent (104,000), which are shown on the graph. Detroit has 632,000 people, making it more than 50% larger than either the Bahamas (407,000) or Belize (400,000). New Orleans (384,000) and Cleveland (373,000) are close behind. So this isn’t a matter of cherry-picking areas with minuscule populations and making them look bad. These cities are the size of small countries, which means we are pretty much comparing apples-to-apples in many of these cases. And if you want to make a real apples-to-apples comparisons, try contrasting American cities to those in other first world countries, like London.

Some may think we’re being unfair to the Black community, zeroing in on their failures as if they’re the biggest problem in the country. But we’re being told to care about the Black community’s plight every day, including by our dear leader, Joe Biden. If I’m going to be forced to care about someone else’s troubles, I’m going to do so honestly. It costs us nothing to be empathetic to our fellow man, but it’ll cost everything to allow that empathy to be exploited. Like I said before, we’re being conditioned to let down our guard.

For what? As

often asks, “What are they preparing us for?” Never assume those in power don’t possess an ulterior motive behind their every utterance. As I explained earlier, the reality of Black crime and interracial crime hasn’t changed one bit - only our perceptions have. Where we were once able to acknowledge what’s right in front of us, noticing itself has become the actual crime. It’s not for nothing - it’s all purposeful. Perception-shaping is a practice every regime, including ours, engages in.And what is that purpose? I’m anti-conspiracism and believe one should never assume malice when incompetence suffices as an explanation. But there’s nothing incompetent about spreading the same falsehood-laden narrative over and over again. They may not be aware that it’s false, but they’re not exactly willing to challenge their own assumptions, either.

Never Let Down Your Guard

You can see the perception-shaping occurring all around you. Watch this video:

I’m not sure where this is from, but it’s a Black man in an interracial relationship with a White woman being depicted as the victim of the notorious “knockout game” by gang members. There’s no real deep analysis required: we all know most urban gang members aren’t young White men and we also know the knockout game was disproportionately “played” by young Black men. What’s depicted is the statistical inversion of what actually happens, proving how little the data actually matters when it comes to shaping perceptions.

But this one really took the cake:

In this video, which I believe to be a dramatization (but cannot confirm), a Black man is depicted as chasing a White woman, who runs inside her home and locks herself in. In the end, it turns out the Black man was only trying to return her wallet. Obviously, the lesson is that we all (White women in particular) ought to never make assumptions about others (Black men especially). If this was really the lesson they were trying to convey, it failed miserably, in my opinion.

First, most people don’t run from someone unless they feel genuinely threatened. There are exceptions, of course, but let’s not overthink things. Women in general have reason to be extra-vigilant when a male stranger approaches them in public. Second, if someone is clearly terrified of you, chasing after them is the last thing you should be doing, no matter how irrational their fear may be. Boundaries are to always be respected. Third, telling someone “open the door” is just as imprudent. What’s a person to think when a stranger is issuing a command like that?

If this was a real-life interaction, there are many different ways a person could’ve handled this scenario. Since this was probably staged, I don’t want to analyze it too much, but the biggest lesson is that if someone doesn’t feel comfortable with you, then break contact, don’t chase them down, all the way home, no less. Turn it over to police, tell them the woman ran from you. If you do follow her all the way home, if she’s not opening the door, just explain why you’re there, leave the property outside the door, then walk away. It’s not your responsibility any longer. Don’t stick around hoping she’ll come outside, thank you, embrace you, and give you her number so you can ask her out.

The insidiousness of these videos is that it shames the public into willful vulnerability. Let your guard down, racist! is the message here. Meanwhile, the reality of crime, along with the relationship between crime and race, is completely inverted or excised in the official narrative. There’s no other reason to do this than to force people to expose themselves to victimization. Why would the Regime do this, though?

For one, we live under anarcho-tyranny. Under this system, the criminal, not the police officer, is the enforcer, using terror to keep us in line. There’s no more cost-effective a way to keep the public’s mouths shut and the tax dollars pouring in than to tell them nobody’s coming to save you, that you, your loved ones, and your property are up for grabs at any time.

There’s another reason: hard times are coming, either way. I’ve said before that the real problem in America isn’t that crime is out of control. It’s not, not yet. The real problem is that the Regime has decided there’s nothing to be done about crime. It assures a more disorderly, violent future, and whether or not we become like South Africa, America’s safest days are probably in the past. It’s better for the Regime the public gets accustomed to the disorder and violence now than to suddenly wake up to reality later.

Whether this plan works or not will be seen in the years to come. For now, it’s what the Regime has staked its legitimacy on. For your part, obey the law, be responsible citizens, and never, ever, let your guard down. There’s nobody coming to save you or any of us. Our well-being will increasingly come down to our personal behavior than ever before. May one day, as a society, we choose to live in accordance with reality.

So… What Are We Being Prepared For?

I appreciate you sticking with this essay all the way through, I know it was a long one. My posting frequency has gone down recently, so not only am I trying to compensate, I’m also trying to fill the coming dead air set to be caused by my upcoming absence.

Before letting you go, someone brought to my attention this essay from fellow Substacker

, which presents something of a counterpoint to what I argued at the beginning of this entry. I’m still working my way through it myself, but I’m enjoying what I’ve read so far, and I may address it in a future entry. He seems to be making a reasoned argument for why complex systems are, in fact, quite fragile, at least when they reach a certain point in their evolution.For now, let’s talk - what did you think of Alex Kaschuta’s interview with Adam Van Buskirk? Do you agree that the system is more stable than often appreciated? Or is there something Buskirk nor I are seeing? How useful an example do you consider South Africa for what lies ahead for America? What do you think of President Biden’s remarks and all the other lies we’re subjected to on a constant basis? Finally, I’ve told you what I think we’re being prepared for - what do you think we’re being prepared for?

Chat each other up in the comments section.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

About the matter of complex systems being better equipped to resist attack or general, unfocused chaos as a result of their presumed redundancy: N.S. Lyons ( pseudonym ) writes one of the most interesting Substacks there is. Since October 7th, conspiracists have been certain the Hamas attack must have been dependent on clandestine Israeli permission, because Israel's border security had layers of redundancy built into it. Lyons' analysis of the attack, which is not paywalled, shows just what clever devils the Hamas planners were: they figured out ways to flip the Israelis' advantages against them by exploiting those redundancies in ways which were so clever and so simple that reading about how they did it should make a reader shocked to find himself admiring their ingenuity.

I am also discouraged by the sheer idiocy and irresponsibility of today’s leaders. Biden’s speech is a prime example of that. When I was a kid, I thunk it was understood that society had to be kept together and basic respect for political opponents is part of that. You didn’t have government essentially declaring large chunks of society beyond the pale and there was an effort to calm tensions.

There was something similar with Trudeau and the Freedom Convoy. You had certain old school types pointing out in the media that a political leader should be calming tensions and reaching out to the other side in times of unrest, but Trudeau and his cronies had none of it.

We also see completely illogical policies these days, such as being soft on crime and then expecting people to take public transit, or pushing electric vehicle mandates but then restricting electrical generation. I feel that once it was understood that decisions have real consequences but now the political class makes sweeping decisions and then expects someone else to sort it out somehow.