The Real Risk To Flying

At least, competency may not even be the issue here.

One more detour, I swear, and we’ll get back to The Next 12 Months series!

Today, I want to talk about aviation. I take it everyone’s familiar with this story by now?

Thank goodness nobody died. This could’ve been very bad. If you want to see just how potentially disastrous it was, watch this video taken aboard the plane while it was still in flight:

https://twitter.com/jasmineviel/status/1745938492600037818

Since nobody died, however, the public’s reaction to the incident has become the main story within the story. I’m not entirely certain how it happened, but immediately, the incident became politicized and the role Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) supposedly played in causing the plane’s window to blow out took front and center, at least on the Right.

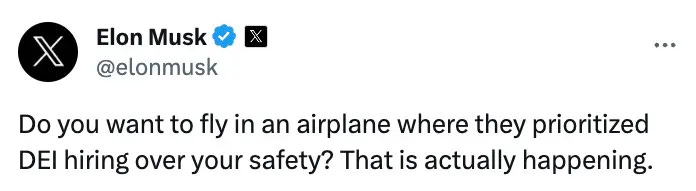

Elon Musk chimed in, showing evidence that Boeing, the manufacturer of the Alaska Airlines 737 aircraft involved in the incident emphasizes DEI over safety and quality:

Nor is this a new argument. For at least the past year, a number of commentators, mostly on the Right, have been warning of a burgeoning “competency crisis,” due in large part, though not entirely, to the prominence of DEI in nearly every aspect of modern life. Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 was merely the vindication for this argument.

Michael Anton, in an essay which otherwise shares my wavelength, said last year:

Ask yourself how long any complex system, much less a whole civilization, can last when it selects people for jobs, including the most demanding and important, on criteria other than merit.

To take just one example, the major airlines recently announced that their pilot corps are too white and male. To “solve” this nonproblem, the airlines have announced a diversity push. Now, obviously there are people of all races, and both sexes, capable of flying planes. But flying an airliner is also a complex job requiring a certain level of smarts and a certain cast of mind (calm and thorough). Not everyone has those things. Hence many who seek to become pilots wash out. Once the airlines start selecting pilots based on criteria other than competence at and suitability for the job, what is going to happen? You can guess. Now apply this lesson across our entire society, because this is happening everywhere.

The argument is convincing and compelling. But just because an argument is convincing and compelling doesn’t mean that’s what’s really happening. As someone who agrees that DEI is a toxic, self-destructive ideology, I have to say that I never bought the idea it’s what’s behind this supposed competency crisis that’s putting lives at risk. I say “supposed,” because I’m not sure this competency crisis even exists. Yet. At least, competency may not even be the issue here.

So, what’s going on? Are the millions who take to the skies at risk? Should we worry about flying and if so, why?

No, Planes Aren’t Falling Out Of the Sky. Period.

First, let’s get the DEI matter out of the way. Coincidentally, as I was researching for this piece, I came across political scientist Richard Hanania’s latest essay on his own Substack. I’m glad I did, because I absolutely don’t mind it when those who, unlike me, make a living talking about this stuff, take the words out of my mouth, making running my own blog easier.

He writes:

I don’t doubt that American institutions are pushing for less competent people to get jobs they don’t otherwise deserve in important fields, and that this has costs. Nonetheless, there is still little evidence that the world is falling apart, and equity initiatives are far from the only ways in which our society deviates from sound policy based in meritocratic principles. One would think that if you predict that planes will fall out of the sky soon due to DEI, and it doesn’t happen, you would step back and wonder what is lacking in your model of the world. In this case, I think that there is something off about how the right thinks about the concept of merit, putting too much emphasis on top-down diktats and not enough on the necessity of decentralized processes designed to aggregate and share information. The case of the missing airline crashes serves as a useful tool to demonstrate this point.

There’s no other way to start a discussion about air safety without first pointing out: air travel isn’t only safer than it’s ever been, it’s arguably among the safest ways to travel.

Since 2000, the fatal accident rate for U.S. airlines and air cargo carriers has remained below 0.03 incidents per 100,000:

It’s not all that different, worldwide, even as it’s safer to fly in some countries than others:

Flying is so safe, do you know how many deaths occurred in the U.S. due to flight from 2011 to 2020? 4,177. That might be 4,177 too many, but consider many of those deaths aren’t the result of commercial air travel, but of general aviation (private and recreational pilots). They constitute 1.1 percent of all transportation-related fatalities during that time. By contrast, over 350,000 have died on the roadways during the same period, constituting over 94 percent of transportation-related fatalities. Your lifetime likelihood of dying in a motor vehicle accident is a shocking 1-in-93; meanwhile, one calculation showed we have a 1 in 260,256 chance of even being involved in an aviation accident.

I often present statistics with the disclaimer that they should never be taken entirely at face value, of course. But if we’re just debating whether planes are falling out of the sky or not, I think the data very clearly proves it’s simply not happening.

Hanania continues, arguing the impact DEI has in general might be less than what we imagine:

Markets Keep Planes in the Sky

When [Anatoly] Karlin argues the “technocapital machine is stronger than DEI,” he gets at the idea that people who spend too much time focused on wokeness tend to drastically underrate Western institutions. The main reason that planes don’t crash as much as they used to is because, as trite as this sounds, airlines have very strong incentives not to kill their customers and crews. They have much more information about their employees and what is good or bad for their business than anyone else does watching from the outside, and it is in their best interest to get airline safety right. Markets drive people to give their money to the companies that best balance safety and convenience, along with whatever else customers value, and employers work hard to avoid hiring individuals who can’t satisfactorily do their jobs. In addition to this, we have our governing and legal institutions, which include the direct oversight of airline safety, and also allow lawsuits against individuals and entities that cause harms through gross negligence.

For this reason, I’ve never worried too much about “woke capital.” I believe wokeness is irrational, and markets are the way we foster and encourage rational behavior. If one sees private businesses doing things that seem stupid like hiring more incompetent minorities than they should, I look first for an explanation based in government mandates, and if there isn’t one, then that opens up other possibilities, like maybe the jobs that the less qualified people are getting don’t matter all that much, or companies don’t actually follow through on the DEI initiatives they promise. Markets are ruthless, constantly rewarding competence, convenience, cost effective measures, and overall providing the best experience for the consumer, who is mostly unsentimental and trying to maximize his own well-being. Given political attitudes among upper class professionals, it’s unsurprising that corporations sometimes go beyond what the law requires on DEI issues, but when they do it’s more likely that they’re engaging in mindless virtue signalling than doing anything that harms the bottom line.

Proponents of the DEI-driven competency crisis theory claim that those running airlines are deliberately putting passengers and even their own employees at risk in the name of Wokeness. But for this argument to have merit, it’d have to be true that lesser-qualified aviators are being placed inside the cockpits of aircraft worth millions of dollars, ferrying hundreds of lives. Without ruling out that some of this could very well be happening, ask yourself: does that sound like a risk worth taking? Put the lives of hundreds in the hands of someone who’s not up to the task over politics?

It’s easy to be overly cynical and simply conclude that they don’t care, as long as they signal virtue and allegiance to the Regime. But if a disaster were to occur, what difference would any of that make? At the end of the day, it’d be their mess to clean up, their loss to absorb. The airline isn’t the government, a newsroom, nor university. It’s the business world, where losses matter. Regardless of why it happened, an airline cannot lose an airframe worth millions of dollars and hundreds of lives in the process and expect to get away with it. That alone blunts any impact DEI might have on air safety.

Really, why would they take such a risk? Just look at legendary carriers Pan Am and TWA, or even lesser-known carriers like ValuJet. Loss of life might not have been the only reason these companies eventually went out of business or got bought out, but they were certainly part of the reason. Pan Am and TWA lost 259 and 230 human lives on a single flight, respectively; how many of you would want to fly with them after that? It’s a stretch to say 9/11 was the airline industry’s fault, yet it still took years for the industry to recover. Many of the major carriers filed for bankruptcy during that time.

Hanania’s entire essay is worth reading and I hope you’ll take the time to do so. For the purposes of this discussion, it suffices to say that the airline industry might say one thing - in this case, express fealty to DEI, the prevailing wisdom of our time - but often times, sentiment doesn’t survive first contact with reality. While there’s certainly immense pressure to conform to DEI, for now, anyway, industries seem to be taking the path of least resistance. Hiring may be diverse, but it remains to be seen how many of these diversity hires actually make the cut. I think the industry has a difficult time admitting to itself that, despite the lip service it pays to DEI, it has no real impact on increasing the diversity of the industry, since reality doesn’t conform to DEI diktats.

One more point before moving on: DEI isn’t exactly new. Since at least the Obama administration, there’s been a concerted attempt to get more women and non-Whites into aviation. Certainly, DEI efforts have kicked into overdrive since 2020 and maybe we’re still early in the game.

But if these numbers are anything to go by, DEI efforts have not made much of a dent at all in the racial and ethnic make up of America’s aviators:

Even as the proportion of White pilots has decreased, this hasn’t seen a marked increase in the number of non-White pilots. Blacks, who are undoubtedly the focus of DEI efforts when it comes to race, have barely budged. If anything, the biggest beneficiaries appear to have been Hispanic/Latinos, who began comprising a larger share of pilots long before the Woke Revolution of 2020. Finally, Baby Boomer retirements can explain some of the decline in the proportion of White pilots.

It could very well be that the proportion of White pilots will continue to decrease into the future. But for now, DEI efforts appear to have been largely unsuccessful in increasing non-White representation among flyers, especially for Blacks. It seems Richard Hanania is correct: the market has its own set of rules, and there are realities no amount of DEI can ever overcome, unless someone really wanted to force the issue.

A Heavy Workload

Does any of this mean we shouldn’t worry about flying? That nothing will ever go wrong? Obviously, that’s not true - the Alaska Airlines incident is the perfect example - but the question then becomes what would make planes fall out of the sky, as those who warn of a competency crisis keep insisting. If not DEI, then what?

Clearly, nobody wants planes to fall out of the sky (I hope), but it’s also true that no winning streak lasts forever. It has been a long time since the last major American aviation disaster and, unfortunately, we need to consider another one will eventually happen. Things like an aircraft window failing in-flight don’t just occur out of nowhere.

Rod Dreher said on his own essay on the topic:

The historian Robert Conquest said that everybody is a reactionary about what they know best.

One of the reasons I wanted to write this piece is because I have a good idea what the real danger is commercial air travel faces. That’s because I happen to know something about it.

I worked at the airport around 10 years ago. I was employed as a ramp agent - loading baggage, pushing off departing flights, then receiving and offloading inbound flights. Later, I worked as part of a crew that maintained infrastructure. It was the best and worst time I ever had on a job. The pay was low, but there are few places as “fun” to work at than an airport. I made some good friends along the way, too. Still, it could be a pressure-packed environment, due to the amount of activity that takes place and the importance of maintaining schedules.

In the airline industry, a one-minute delay is substantial. All delays need to be accounted for, explained, and “blamed” on someone, be it the ground crew, the gate agents, or the air crew. Rack up enough one-minute delays and people higher up will want to know what’s going on, why a schedule can’t be kept, why you’re holding everyone else at the airport up. There are very few industries out there that take delays as seriously as air transport.

For good reason. Airports are crowded places. You only have so many gates, so many ramp personnel, and even the conveyor belt system handling your luggage can only handle so much throughput at one time. There’s a tremendous amount of activity that needs to occur to get a single flight in the air. For the ground crew, which was my lane, there was loading luggage onto carts, taking it out to the plane, loading it onto the plane, replenishing the potable water, and attaching the tow bar to the nose gear. It all sounds simple, I know, but the ground crew isn’t always working the same flight. Sometimes, they’re working multiple flights at once, but you also cannot push off or receive a flight without a full crew present at a gate. Finally, the plane needs to be fueled and mechanics need to resolve any issues that might exist.

After one plane departs, its off to another gate to prepare to receive another flight. At most, you might get a one-hour break, but that single hour goes by very quickly. Once the flight arrives, the luggage needs to be offloaded and delivered to the baggage claim. A custodial crew needs to enter the plane and get it cleaned up for the next group of passengers. Catering needs to come and stock meals and refreshments. You can see how even a short delay can make an already pressure-packed situation more stressful. There’s a lot of people, lots of moving parts, and everyone has their own schedule to maintain. The ramp crew doesn’t necessary follow the same schedule as the fuelers, for example, even though they’re all servicing the same flight.

Contrary to popular opinion, airports don’t operate around the clock, not exactly. Generally between midnight and, say, 6 am, those hours are seen as necessary downtime for maintenance, preparing for the next day of flights, and, of course, rest. That still leaves at least 18 hours for non-stop flight operations but again, think about how many flights are taking off and landing during that time. Major U.S. airports service a couple thousand arrivals and departures daily, most them arriving or departing during certain times (creating peak hours). This is day in, day out. It’s truly one of the most incredible feats managed by human civilization, one I was proud to be a part of in my own small way.

Where am I going with all this? Running an airport isn’t an easy operation, clearly. You’d think with all these moving parts, eventually, something would fail spectacularly, costing lives. Sometimes, it happens. And yet, it often doesn’t, not anymore. The assurance you can board a plane at Point ‘A’ and step off that plane at Point ‘B’ without incident is as close to a guarantee as it’s ever been. The demand for air travel is sky-high and continues to soar (puns intended), yet the system is handling the workload. Passenger traffic at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the world’s busiest, peaked in 2019 with over 110.5 million passengers passing through. The percentage of on-time departures and arrivals was 82% and 85%, respectively. Less than 1% of flights were canceled all year. Since then, the numbers have remained consistent. Does that sound like a competency crisis to you?

So what worries me? I just don’t know how much more demand the industry can take. In many ways, the industry is bearing a workload it was never meant to handle. Like most things, the airline industry was built up with the expectation of growth in mind, but I’m not sure anyone anticipated this much growth. Ironically, the COVID pandemic of 2020 provided what I thought was a much-needed break for the industry, even if they ended up taking a financial hit in the process. My hope is that they took the downtime to take a look at data and see if there were any warning signs, any issues with potentially serious consequences, and addressed them before everyone went back to flying again.

Did they? It’s hard to say for sure. I regret I’m taking so long to get to my point, but I think a basic understanding of where our industry is today and how heavy a workload it’s handling is a big part of the story, one not enough Americans are aware of. We also need to understand nothing can grow forever and, eventually, everything hits the point of diminishing returns. What happens then?

For that, we look at what happened when a heavy workload overwhelmed a different type of flying program.

“Go Fever”

What’s happening to air transport reminds me of the early years of NASA’s Space Shuttle, which flew from 1981 to 2011. Over that 30-year service life, the shuttle racked up 135 flights. Overall, it was a success story, though it was also marked by two very public failures.

The first was the loss of Space Shuttle Challenger on January 28, 1986. Up until that point, everything had seemed to be going well for the program. In less than five years, NASA racked up 24 flights, with Challenger’s fateful flight being the 25th. In 1985 alone, the shuttle fleet flew a record nine missions. By comparison, the Apollo program, arguably NASA’s grandest achievement, flew 11 missions in four years.

Obviously, technology had advanced in the intervening years and the shuttle was a different kind of spacecraft. NASA viewed the shuttle as effectively a space plane, treating it the same way airlines regard aircraft. But flying 24 space missions in five years is not the same as running an airline. NASA was attempting to stick to a break-neck schedule which, at least in retrospect, seemed untenable. Throughout the record year of 1985, a shuttle would launch, return, then another would launch within a few weeks. Challenger’s final flight came only 10 days after the last shuttle returned to Earth; originally, it was set to depart almost a full week earlier. At one point, there were shuttles parked at two separate launch pads. This was a schedule which NASA had never attempted before.

Nor did these missions go anywhere as flawlessly as most believed. There was plenty of drama that went on outside the public eye. The O-ring problem which resulted in Challenger’s demise was identified years earlier and on previous shuttle missions. The disaster could’ve very well occurred one year prior. During the flight prior to the Challenger disaster, a fatigued technician allowed 4,000 lbs. of liquid oxygen fuel to escape from the external tank. The error, which would’ve been fatal, was noticed 31 seconds prior to lift-off, allowing the launch to be aborted.

And yet, NASA kept pushing. Fueled by “go fever,” the desire to keep the wheels turning and burning at all costs, nobody was willing to throw their hands up and bring the entire show to a screeching halt, even though it was unquestionably the right thing to do as NASA was headed for disaster. The night before Challenger’s launch, engineers at the contractor that produced the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters using the problematic O-rings emphatically warned their superiors and NASA not to launch. They did, anyway.

The loss of Challenger wasn’t just a failure in engineering, but a failure in leadership and management. Often times, it takes a disaster for organizations and those who run them to wake up and address problems that were obvious all along. But those who run organizations are humans and humans harbor a bias for normalcy.

There were, however, very few who would’ve described NASA as “incompetent” during the first several years of the shuttle program. Results matter; so long as the spacecraft launched and returned home with all crewmembers alive, everything was fine, even if, underneath it all, there were serious issues requiring redress. I have to wonder if this is something that’s going on with the airline industry - that maybe safety might end up being taken for granted.

Going back to commercial flying, if safety is being compromised, it’s not being compromised at the airports. It’s been a long time since I’ve worked there, but whatever my experience is worth, I’ve never witnessed anyone take shortcuts or deviate from procedure in the name of expediency. Sure, everyone bends the rules from time to time, but I’m talking about anything concerning the safety of passengers, crew, and security. Everyone hates delays, but if that’s what it takes to keep an airplane from falling out of the sky, they’ll happily take the delay, no matter how many hours it lasts. Pilots aren’t always easy to work with, but a lot of that has to do with the fact they’re ultimately responsible for what happened to the flight, to say nothing of the fact it was their own lives on the line. Again, nobody wants a plane to crash and aviation is so heavily-regulated, anyone who cannot follow procedure simply won’t sit inside a cockpit, no matter their race, gender, or sexual orientation.

To the extent safety is being compromised at all, I fear it may occurring much earlier in the chain - at places like Boeing, at the various sub-contractors who produce their planes and their constituent parts. Spirit AeroSystems, the company producing the fuselages for the Boeing 737, was already subject to a class-action lawsuit before the most recent Alaska Airlines incident over quality control issues:

However, the way the quality control processes of Boeing and Spirit work with each other is also under scrutiny. And this led some reporters to a very recent class-action suit against Spirit AeroSystems, filed on the 19th of December last year.This class action suit was filed by investors who bought Spirit stock and believe that they were misled by Spirit’s representatives, regarding key operations in the company. The class action suit (that you can see HERE) alleges that Spirit AeroSystems’ management knew of at least one of last year’s 737 quality control lapses: the tailfin bolts and mis-drilled rear pressure bulkhead holes.

According to the suit, Spirit didn’t just keep these quality control lapses secret from its investors. It also didn’t inform Boeing about them. Joshua Dean, a Spirit mechanical engineer who worked in a quality control position, raised the alarm about those mis-drilled holes in October 2022.

Boeing didn’t learn about this until its own engineers discovered it around August 2023 – 10 months later. Dean reported the issue on multiple occasions to his superiors, identifying the causes of the misalignment that led to the mis-drilled holes. Again, all this is according to the class action suit.

Spirit eventually fired Dean in April 2023. He felt that the company made him the scapegoat for the tailfin bolt issue, which he hadn’t discovered. Dean alleges that Boeing discovered the rear pressure bulkhead issue while working on the defective tailfin bolts, since the two are very close to each other.

There are some parallels to NASA during the shuttle program. Even when issues were identified and reported, corrective actions apparently weren’t taken and the show was forced to go on. Thank goodness, unlike Challenger, the disaster that convinced everyone to finally stop and take a good look at what they were doing didn’t kill anyone. But how seriously will they take this latest incident, where the industry unquestionably dodged a bullet? The fact this incident resulted in no loss of life means it’ll probably cast a much shorter shadow than if it did. Once everyone forgets about it in short order, will the industry attempt to force everything to go back to normal? There’s money to make, after all. Remember: NASA dodged many, many bullets for years before they finally lost astronauts and a spacecraft.

The industry responded by grounding much of the Boeing 737 MAX (the variant flown by Flight 1282) fleet, but you may be shocked to discover this isn’t the first such grounding. A previous grounding occurred in 2019 to 2021, further raising concerns there may be a more serious problem than meets the eye. Even the U.S. Secretary of State was affected.

Is aviation headed for its own Challenger moment? If so, what can we do about it?

To Fly Or Not To Fly?

To summarize - the data says DEI isn’t causing flying disasters, flying is as safe as it’s ever been, and yet the prospect for disaster looms. What are we as preparedness-minded folks to do with this information?

Once more, I’m happy to let someone else have the floor, this time risk expert David Ropeik. He wrote back in 2006:

Trying to judge whether a particular risk is big or small is, well, a risky business. There's a lot more to it than you might think. Flying in airplanes is a case in point. You'd think that you could just find out the numbers—the odds—and that would be it. The annual risk of being killed in a plane crash for the average American is about 1 in 11 million. On that basis, the risk looks pretty small. Compare that, for example, to the annual risk of being killed in a motor vehicle crash for the average American, which is about 1 in 5,000.

But if you think about those numbers, problems crop up right away. First of all, you are not the average American. Nobody is. Some people fly more and some fly less and some don't fly at all. So if you take the total number of people killed in commercial plane crashes and divide that into the total population, the result, the risk for the average American, may be a good general guide to whether the risk is big or small, but it’s not specific to your personal risk.

Similarly, when victimized by crime, nobody goes, “Oh well, crime rates are overall low, so I guess what happened to me isn’t such a big deal!” No, it’s a big deal because it happened to you. To say nothing of the fact there’s a massive difference between crime and flying: the former can only be bad (unless you ascribe to anarcho-tyranny) while the latter has been a net positive to society.

And even if it’s safe, so what? Shall we fly all the time, then? Likewise, if crime rates are so low, so what? Shall we leave our doors unlocked, our property unattended? Ignore our personal intuition that says someone ought to be avoided, even if it means enduring harsh public judgment?

As Ropeik goes on to say [bold mine]:

Numbers are not the only way—not even the most important way—we judge what to be afraid of. Risk perception is not just a matter of the facts.

What I’m getting at is this: data alone should never be used as the only metric for assessing risk. Not only does context matter, but people more powerful than you and I are always trying to dictate when the data matters and when it doesn’t. We need to be discerning and use data not to draw broad conclusions, but to keep things in perspective, using them to guide our decision-making, not make them for us. There’s no such thing as a risk-free environment; at some point, we’ll need to roll the dice and take some chances.

Ropeik next says something that’s been on my mind this whole time I’ve been writing this essay [bold mine]:

Researchers in psychology like Paul Slovic and Baruch Fischhoff have found that when we have control (like when we’re driving) we’re less afraid, and when we don't have control (like when we’re flying) we're more afraid. That probably explains why, in the first few months after the 9/11 attacks, fewer people flew and more people chose to drive. Driving, with its sense of control, feels safer. Studies at Cornell and the University of Michigan estimate that between 700 and 1,000 more people died in motor vehicle crashes from October through December of 2001 than during the same three months the year before.

It’s funny - we feel safer when we drive than fly, yet we’re more likely to die driving than we are flying! This despite the fact as drivers, we are in total control of the vehicle, if only in a nominal sense. It raises an interesting philosophical question of whether our own hands are truly the safest of hands; I’ll let you ponder that on your own.

No, I’m not saying we shouldn’t be able to have our own cars nor make our own decisions. What I’m saying is that you ought to use the facts to re-consider your own assumptions and fears. If you’re afraid you might get on a plane and never get off, consider how often you get in a car and risk never coming home. Or maybe ask yourself how many people you know were involved in a plane accident. It pales in comparison to the number of people you know were involved in a motor vehicle accident, doesn’t it?

If nothing else, consider that the Sunday after Thanksgiving this past year was the busiest travel day in U.S. history. If anything was bound to go wrong, it was on just such a day. And yet:

When the results don’t jive with the noise, what are you going to go with when making big choices?

DEI: “Denying Evidentary Information”

This post has gone on much longer than anticipated, but I do need to address something regarding DEI itself.

I keep the culture talk down to a minimum on this blog. Yet even when it comes to DEI, I can make a pragmatic argument for why it’s bad and should be resisted at all costs: it’s in defiance of reality.

A week ago, I came across this strange tweet:

Hmm. Has this been your experience? That most everyone is capable of doing most jobs with the right training and team? For context, the tweet was in reference to the matter of using DEI to diversify the American aviator pool. Proponents of DEI claim it’s only about overcoming systemic prejudices and that DEI cannot possibly negatively impact competency, because we are all at once unique, yet all equally capable, even at something as high-skill as piloting.

Let’s assume the following statement is true, absurd as it may sound: we might be different, yet we’re all capable of achieving the same level of competency. Does this change the fact that some people don’t learn as well as others? That some people take forever to catch on, while others catch on much quicker? That some people are capable of understanding simple instruction the first time, while others need to be told over and over again until they get it, if they get it at all? That some people possess intangible attributes like common sense and “command presence,” while others overthink their way into breaking a door they could’ve just opened instead, or cannot deal with a variety of personalities as the job demands? That some people have patience, others more impulsive, some have no impulse control at all?

Clearly, even the best workers need to be taught at first and given opportunities to fail. That’s not in dispute. What’s in dispute is the idea that everyone is worth the trouble. This flies in the face of real-world experience, something I think we can all attest to. Even if everyone can become good at a job with the right training and team, the law of diminishing returns still applies. Training, after all, takes time and resources. If someone takes years to learn how to do a job that takes most people months to learn, what benefit are you going ultimately going to receive from trying to train that employee? That’s time and resources that could’ve been devoted to other employees who’d catch on quicker and start contributing to the organization quicker.

If it was simply a matter of the “right training and team,” there would be no need for standards, no need to pass or fail anyone, no need for job requirements. Again, bad ideas don’t survive first contact with reality. This is especially true for high-stakes professions like aviation. When lives and millions of dollars of equipment are at stake, you cannot just continue training an individual who repeatedly fails to demonstrate the aptitude, knowledge, and wisdom required to do the job. While employers shouldn’t expect someone to know how to do the job correctly on the first day, it’s more than fair to expect them to demonstrate the competence necessary to learn the job in the first place. If you need to teach someone who wants to be a construction contractor how to perform basic arithmetic and use a ruler, that calls for more schooling, not paid, on-the-job training. Employers have every right to expect a return on investment. Even paid apprenticeships have entrance standards for a reason.

Finally, humans aren’t robots. Competence isn’t something that can simply be programmed. I can’t say I’m the biggest fan of Malcolm Gladwell, but he once defined talent as something you’re willing to invest time and energy into being good at. I think there’s a lot of truth to this. The person doing the learning matters as much as the person doing the teaching. Someone who isn’t fully committed to doing something probably shouldn’t be doing it at all. When someone is taught, they need to receive what’s being taught to them. Unfortunately, some people are in no mood for learning, have no interest in the topic, or cannot handle the level of knowledge being thrown their way. You cannot force-feed knowledge to anyone, especially adults. We’ve all known someone who simply couldn’t be taught. It wasn’t always because the teacher was bad.

It may hurt the pride of someone to say we’re not all meant to do what others do. That doesn’t make it a lie.

Are The Skies Still Competent?

I want to close by saying that I’m in no way arguing the aviation industry is in dire straits, on the verge of predictable catastrophe. I guess the whole point of this piece was to refute the argument that planes have been falling from the sky or that they’re about to. I also wanted to remind everyone there are indeed risks to flying and offer my own take on what I think to be the more serious issue plaguing aviation today: overwork. Politics should never get in the way of facts, but unfortunately, it seems far too many have succumbed to something of a moral panic concerning the impact DEI has on flying.

At the same time, nobody should ever be hired, especially for a high-stakes profession like aviation, on the basis of race, gender, or sexual orientation. Even if DEI isn’t what’s threatening competence, the fact that it has a place in the industry at all is troubling. Recruiting and training the right people for the job is a tough task; DEI distracts from the objective of finding people who possess the aptitude, knowledge, and wisdom necessary to perform it. Those traits may or may not fall along race, gender, or sexual orientation lines. It shouldn’t matter. If everyone can do the job, nobody cares what they are. If not everyone can do the job (and no, not everyone can do everything), then nobody should be shocked there’s resistance to diversifying professions. You can never argue in favor of anything other than “most capable gets the job.”

Last thing: how come nobody decries the fact tree trimmers are over 95% male, nearly two-thirds White, with little, if any, LGBTQ+? Or that miners are over 90% male, three-quarters White, and less than 5% Black? Could it be that not only are these two of the deadliest jobs in America, they don’t pay well and lack the high status of other professions, like being a pilot for a major airline?

Time To Chat

Are you surprised to learn how safe flying actually is? What problems, if any, do you see in aviation? Do you think DEI has been having a detrimental impact on the industry? If so, what is it? Are you afraid of flying?

Share your thoughts in the comments section.

UPDATE: Reader and Substacker “Katja” writes:

Commercial flight in the US is incredibly safe - if I remember correctly, there have only been two commercial airliner deaths in the US since 2009 - the very famous Southwest flight from a few years ago where a passenger was killed (and nearly got pulled out through the window) and a less famous botched landing up in Alaska. I think one thing that you're missing, though, is that a lot of the reason that airline travel in the US is so safe is because not only do we take the safety seriously, we have built an incredible amount of redundancy in systems so that if one fails, there's another to “catch” it. As a result, we’re not going to see a true breakdown in aviation until multiple layers of redundancy have been breached - and there certainly is danger intentionally creating “soft spots”, which depend on the other redundancies to hold to allow for things to “pass”.

I agree that redundancy is a big reason why flying has become so much safer. I can only imagine how many potential disasters have been virtually eliminated due to the presence of back-up systems. Some pilots will tell you flying is more about systems management these days than physically operating a machine.

That said, redundancy is primarily a technical matter. When it becomes to people, there’s not quite as much redundancy. Then it becomes a simple matter of showing up, knowing what to do, and doing it. There really is no substitute for people knowing the job and doing it, following procedure, etc. It’s also for this reason I’m just not sold on this competency crisis. There’s a job for just about everyone in the aviation industry and everyone is pretty much where they need to be. There are profits, property, and lives at stake. I know my blog focuses on the unpleasant realities of life, but there’s another side to life as well, where people do act rationally when tangible goods - like money and people - are on the line. Even if a certain amount of incompetency is tolerated, even the most DEI-centered employer won’t waste money on someone who threatens the bottom line or nearly kills someone.

Still, you need to wonder if technical redundancy is being taken for granted. I came across a 2019 article from The Seattle Times regarding the Boeing 737 MAX, the aircraft at the heart of the current controversy. It’s paywalled, but I can share the opening three paragraphs:

Boeing has long embraced the power of redundancy to protect its jets and their passengers from a range of potential disruptions, from electrical faults to lightning strikes.

The company typically uses two or even three separate components as fail-safes for crucial tasks to reduce the possibility of a disastrous failure. Its most advanced planes, for instance, have three flight computers that function independently, with each computer containing three different processors manufactured by different companies.

So even some of the people who have worked on Boeing’s new 737 MAX airplane were baffled to learn that the company had designed an automated safety system that abandoned the principles of component redundancy, ultimately entrusting the automated decision-making to just one sensor — a type of sensor that was known to fail. Boeing’s rival, Airbus, has typically depended on three such sensors.

Once more, we see that Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 is just the latest in a long string of incidents suggesting major issues with the 737 MAX. We also see that if a competency crisis exists, it rests with the people designing the plane, not those flying it. It’s still not clear if DEI is the underlying cause (I doubt it), but we can at least agree DEI isn’t something that’s going to correct the problem.

This is why the parallels with NASA and Challenger are so difficult to shake off. The Boeing 737 has been, for at least a decade or two, the workhorse of the airline industry. Challenger was, at the time of its demise, the workhorse of a four-shuttle fleet, despite not even being first-built. There was nothing wrong with Challenger itself - it was the externally-attached solid-fuel rocket boosters that destroyed it - but the point is that in both cases, you have complex systems being forced to meet an insatiable demand in the face of glaring problems.

Still, I do agree with Katja; the airline industry has many points of failure, but the number of fail points is itself a robust defense against disaster. One disaster is one too many, but I think the results speak for themselves: despite the heavy workload, the industry is getting the job done. We shouldn’t take anything for granted, but we shouldn’t discount the successes, either. The fact that so many disasters don’t occur despite the conditions being rife for catastrophe needs to be part of the discussion.

UPDATE #2: Reader “Reckoning” writes:

There is some reason for concern that, as true believers take over from the boomers, they will believe their own BS and refuse to take no for an answer.

He’s talking about DEI. It could very well be it’s yet to rear its ugliest head. That said, I think the prospect of death is still a very powerful deterrent against allowing anyone to become pilots. I can attest from personal experience that even employers who are committed to DEI still get rid of employees who cannot do the job, though the decision to take them off the playing field is nonetheless gut-wrenching for them. People often do irrational things - DEI being a great example - but when reality strikes, people suddenly become rational, even as they engage in revisionist history to justify their decision-making.

Going back to Richard Hanania’s own Substack essay on the topic:

The only plausible case you can point to where something like wokeness or DEI arguably destroyed a nation is South Africa, but the demographics had to be really bad for that to happen. If we’re ever at the point where blacks make up 80% of America and whites are down to 7%, then wokeness could become as much of a threat as anti-trade and pro-union policies. And even South Africa is not nearly as big of an economic basket case as Argentina and Venezuela have been.

Folks like me often speak of the “South Africanization” of America, but this is more figurative than literal. The fact 80% of South Africa is Black is a huge part of the story; not only is the U.S. still predominantly White, the racial demographics of aviators have, as I’ve shown, not changed much despite living in such liberal times. It’s still very possible Whites become a minority in the U.S. within our lifetimes, but even then, the lopsided demographics of a country like South Africa is still highly unlikely.

More from Reckoning:

There is also the matter of justice. Even if all the diversity hires are competent, it’s not fair to reserve the choice jobs for minorities and some white nepo babies. I would like my children to have an equal opportunity in this society for the best jobs such as pilot, professor, doctor... But unfortunately RW politicians are averse to frankly and energetically pursuing the interests of their constituents.

The best argument anyone, politician or otherwise, can make against DEI is that not everyone can do anything. Some people simply don’t possess the intangibles necessary to do certain jobs, ones where lives and valuable property are at stake. Since recruiting and training takes money and time, it simply doesn’t make sense to hire anyone other than those who are most capable of doing the job and most likely to want the job.

Of course, DEI is premised not only on the idea we are all equally capable of doing most jobs, it’s premised on the belief people who want the job are being denied it due to prejudice. If people believe something with religious fervor, facts won’t sway them.

The existing dynamic is one where employers seek diversity, equity, and inclusion so they don’t draw hostility from the Regime, but beyond that, attempt to maintain standards so they can remain in business. I don’t know about you, but I don’t see why this dynamic couldn’t be sustained indefinitely.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

Commercial flight in the US is incredibly safe - if I remember correctly, there have only been two commercial airliner deaths in the US since 2009 - the very famous Southwest flight from a few years ago where a passenger was killed (and nearly got pulled out through the window) and a less famous botched landing up in Alaska. I think one thing that you're missing, though, is that a lot of the reason that airline travel in the US is so safe is because not only do we take the safety seriously, we have built an incredible amount of redundancy in systems so that if one fails, there's another to "catch" it. As a result, we're not going to see a true breakdown in aviation until multiple layers of redundancy have been breached - and there certainly is danger intentionally creating "soft spots", which depend on the other redundancies to hold to allow for things to "pass".