The Next 12 Months: Part II - Crime

What crime statistics fail to capture is what America’s problem actually is.

The Left and the elite class took a victory lap recently, reveling in a report showing that crime became less of a problem throughout the United States during the last 12 months.

Crime in the United States has declined significantly over the last year, according to new FBI data that contradicts a widespread national perception that law-breaking and violence are on the rise.

A Gallup poll released this month found that 77% of Americans believe crime rates are worsening, but they are mistaken, the new FBI data and other statistics show.

The FBI data, which compares crime rates in the third quarter of 2023 to the same period last year, found that violent crime dropped 8%, while property crime fell 6.3% to what would be its lowest level since 1961, according to criminologist Jeff Asher, who analyzed the FBI numbers.

Murder plummeted in the United States in 2023 at one of the fastest rates of decline ever recorded, Asher found, and every category of major crime except auto theft declined.

Yet 92% of Republicans, 78% of independents and 58% of Democrats believe crime is rising, the Gallup survey shows.

“I think we’ve been conditioned, and we have no way of countering the idea” that crime is rising,” Asher said. “It’s just an overwhelming number of news media stories and viral videos — I have to believe that social media is playing a role.”

Does the data support the conclusion? Short answer: yes. Long answer: yes, but there’s a lot more to it.

Sample Size Matters

Year-to-year changes are useful and shouldn’t be dismissed offhand. However, any data analyst worth their salt will tell you small sample sizes are unreliable for drawing conclusions. So while crime has fallen the last year, does that obliterate the narrative that crime is on the rise in America?

You be the judge:

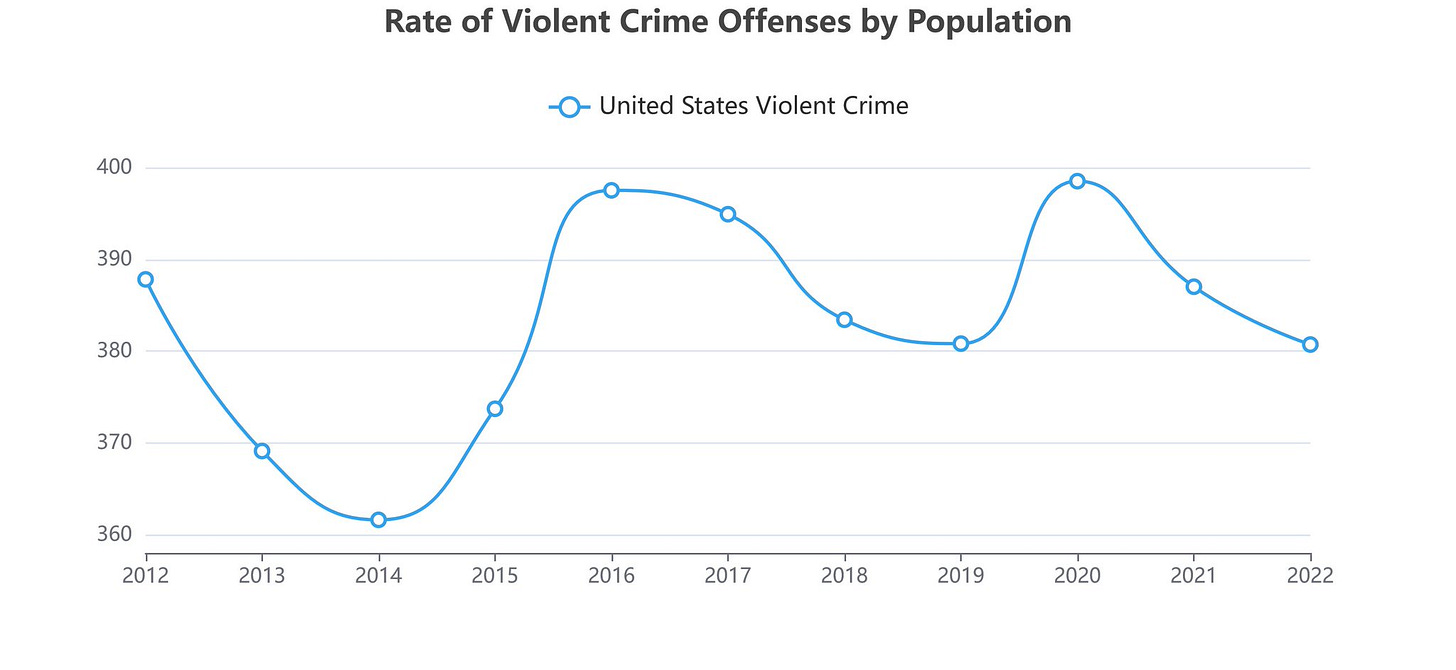

Those who believe crime isn’t on the rise in America often claim we’re in an era of “historic lows” in crime. However, as the graph shows, that historic low was struck in 2014. In about a week, 2014 will be a decade in the past. Since then, the trend has clearly been upward, even as crime has fallen in the past year. This is a phenomenon I’ve mentioned on more than one occasion in this space. Perhaps this is why the analyst mentioned in the story above cites 2019 as the new baseline, because citing 2014 would change the narrative rather dramatically.

Does the big drop-off really mean anything in itself? Sure, it means something, but again, sample size matters.

Take a look at this graph showing violent crime rates from 1960 to 2013:

Notice the big dips that took place in the 1970s and 1980s. If we hewed strictly to the data, anyone who thought in the early-to-mid-1980s that crime was worsening would’ve been regarded as un-tethered from reality, at least by today’s ruling class standards. Sure, context matters - Americans back then had been living in an environment of escalating crime for at least a decade by that point - but if the data is what matters most, then Americans had no reason to believe that crime was worsening during the early-to-mid-1980s.

And yet, America was at that point still several years away from the historical peak of violent crime. When things appeared to be getting better, they suddenly got worse - and worse - and it’d be at least a generation before people began to notice life was becoming safer in America. The point isn’t that things are going to get worse (though that’s certainly my gut feeling). It’s that short-term declines mean only as much as short-term increases. Perceptions and sentiments take time to reverse themselves and the reason why crime has once again become a political talking point is because, over the last decade, crime has gotten worse and people are taking notice.

So we have something of an opposite problem from years gone by - whereas once Americans seemed unaware crime had gone down, the expert class today seems oblivious or unwilling to admit that since striking “historic lows,” crime has gone back up, even if calling it a “wave” is hyperbolic. Even during 2020 into 2021, talking about worsening crime was considered off-limits, as the prevailing sentiment of the time was that law and order was bad because “Black Lives Matter.” Now that people are noticing crime might be a problem again, it’s time for those in power to push back and the numbers seem to bolster their case.

What Are They Trying To Say?

Crime is, like everything else, a politicized issue. We build and maintain civilization in large part to deal with things like crime and yet we’re at a point in our civilizational life cycle where we can’t agree on what the answer to dealing with crime is, or if crime is even a bad thing.

The answer to the question of whether crime is a major problem in America depends largely on what kind of story someone is trying to tell about the country. The most prominent such story is when the Left downplays the prevalence of crime (often citing statistics from almost a decade ago in doing so), while decrying the prevalence of “gun violence.” Certainly, the U.S. has a tremendous amount of gun violence compared to the rest of the developed world, but the Left decries gun violence not because it’s worried about crime, but because it’s opposed to gun ownership in principle. They view anyone who owns a gun, regardless of why, as having an equal propensity for committing violent acts.

The “Two Americas” are living in two separate worlds when it comes to crime. According to the Left, crime may not be a problem, but gun violence most certainly is. The two issues are regarded as separate from one another, but they’re not - gun violence is a problem in this country because firearms are the weapon of choice for criminals. If every last gun was seized from public hands, criminals would simply shift to other means of violence. We’re not talking about reasonable folks who suddenly decided to hurt someone just because a gun ended up in their hands.

An alternative reading is that “gun violence” is the Left’s stand-in for crime. To distinguish themselves from the Right, the Left instead focuses on the means of violence instead of the act and the perpetrator. This means the Left is actually concerned about crime - the fact they’ve been arming themselves suggests as much - but for political purposes and for signalling loyalty and virtue, they frame the issue differently. I think this carries much truth. Leftists are human, after all, and no matter what they might say when everyone’s watching, they lock their doors and call 911 when something bad happens to them.

There’s also something missing in any conclusion that crime isn’t as big a problem as people think it is: then what? What do you expect people to do with that information? Shall Americans let their guard down and be less prepared to deal with crime in their daily lives? Can we leave our doors unlocked and our property unattended? Sure, it’s good news that crime is going down and we should certainly factor that into our personal risk assessments, but it’s not an argument against preparedness. The only conclusion worth drawing from the data is that none of us should be preoccupied by crime, which is a sentiment I agree with.

Questioning one’s motives is a tactic often attributed to conspiracy theorists, but I don’t think it ever hurts to ask, “What are they preparing us for?” to quote Rod Dreher. Jeff Asher, the analyst featured in the story, is someone I’ve cited previously. I have little doubt he’s an honest interlocutor, though I have to admit, he comes off in this story as someone who’s getting paid to get people to worry less about crime. I, too, would like Americans to worry less about crime, but I also think it’s important to become more aware of it so they can accurately assess risk and factor it into their life plans.

Asher once attempted to explain why Americans are supposedly so bad at assessing crime trends. While it’s true what the public thinks is happening often isn’t the same as what’s actually happening, it’s also an unfair criticism. Most Americans aren’t data analysts, nor do they view the world through the lens of data. This is both good and bad, but the point is that data does have limits with respect to assessing one’s personal sense of risk. An 8% decline in crime sounds nice, but if, say, your neighborhood is struck with a wave of robberies, suddenly, the fact that crime is going down countrywide doesn’t mean anything to you.

It’s also true that crime isn’t the only trend Americans are bad at assessing. They notoriously overestimate the number of unarmed Blacks who get shot by police (although, since 2019, perceptions have improved somewhat) and they grossly underestimate the number of illegal immigrants who cross the border. It’s worth noting - on the matters of Blacks being shot by police and illegal immigration, the public appears to believe exactly what the ruling class would want them to believe, despite it being wrong.

But crime? Not only is it wrong, but it works against the Regime, so it’s absolutely imperative to change this perception. I’m not going as far as to say Jeff Asher is part of such a high-level effort, but my point is that Americans are bad at perceiving trends in general on a wide array of issues and this isn’t unique to crime. They should be corrected, of course, but not only when it’s convenient to the ruling class. It should also be understood why people think crime is increasing: put another way, if everyone in your immediate vicinity is catching a cold, is it a reasonable to think everyone’s catching colds too, whether the data ultimately shows a nationwide cold epidemic or not?

In his attempt to criticize Americans’ perceptions of crime, Asher cites the role social media has played in shaping perceptions:

Moreover, the spread of social media and video technology has made it infinitely easier to film and publicize a viral crime incident such as a large scale shoplifting spree. There are millions of property crimes occurring each year, but these outlier incidents become the glue people rely on when guesstimating whether crime is up or down. My neighbors never post on NextDoor how many thousands of packages they successfully receive, only video of the one that randomly got swiped.

But when crime was actually going up, people didn’t have access to social media. All they had was access to the nightly news or their own personal experiences and they were right to be worried that crime was going up. Social media should never be regarded as representative of reality at large, no, but it cannot be tossed into the wind, either. When someone records someone swiping their packages from the front door, they’ve recorded something that’s actually happened. Multiply that one incident across a zip code and you can see why people may believe, how ever mistakenly, that crime is getting worse cross-country. Remember: crime might be something that happens even on a good day, but it’s not supposed to. It’s the antithesis of civilization and nobody expects to become a victim of crime, even as they’re prepared for the possibility it could happen to them.

Not every wrong thought is an unreasonable one. Thinking crime is getting worse is more reasonable than thinking hundreds or even thousands of unarmed Blacks are being shot by police or that just a few hundred thousand migrants (which is still a lot) cross the border illegally each year. We rely almost entirely on the authorities and the media for information on both, meaning the public is even more susceptible to manipulation, given especially that both topics are emotionally charged, making calm, reasoned discussion nearly impossible.

A reader named

replied to Asher admonishing the public for being ill-informed on the statistical realities of crime:But do we run a risk of downplaying concerns about crime? Those of us who are/were in the mainstream justice system came into direct contact with endless people victimized by “minor” crimes who were so negatively impacted that they moved or restricted their movements or who spent thousands on security systems or bought firearms (now in 50 percent of households per Gallup).

I'm aware of a newly hired news director for a Baltimore TV station who wanted to live in the city but their garage was broken into three times to steal bikes. They moved 30 miles away from the city. I just finished reading a story about e bikes in NYC having the potential for solving an array of problems but people keep stealing the bikes.

After personally witnessing (and assisting) multiple victims of crime, their reactions are posted on social media and shared with family and friends. This is multiplied many thousands of times daily. We may believe that their distress is an overreaction based on inaccurate data but, to them, it's real fear with considerable consequences.

I’m unwilling to suggest that that their feelings are invalid (and I understand that's not what you’re saying) but what we consider “minor” crimes lives with them and their friends and family for a very long period of crime.

Now, take it to the next level of violent crimes. The examples of human distress are literally endless with people living their lives in fear and they share that fear with every Facebook photo of them sleeping with Pitbulls. It’s the well documented instances of people living in high crime areas with PTSD.

So I’m torn between a statistical approach as to how people “should” feel and how crime has affected them. I’ll go back to my experience posting on a Reddit group where I was called every name in the book with people saying that I was “fear mongering” for posting the same data.

Remember: the same people who’d have you worry less about crime also believe you ought to be worried more about Blacks shot by police and and less worried about illegal immigration, all in defiance of statistical realities. I want to state once again I’m not accusing Asher of being part of such an effort, but there’s no denying people are constantly trying to shape our perceptions by picking and choosing when the data matters and when it doesn’t.

The public should be corrected when wrong. But accompanying the correction should be an understanding of why it matters that they’re wrong. If perceptions need to change about crime, to what end?

What’s Really Going On

In a separate post, Jeff Asher explored the possibility crime may be underreported, contributing to the statistical decline of crime across the U.S. After all, if a crime wasn’t reported, then how does anyone know if it happened?

Asher puts the issue in numbers:

That all crimes don’t get reported to the police is well known. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) for 2022 found that 48 percent of violent crimes (as the FBI defines them) were reported to the police in 2022 and 31.8 percent of property crimes were reported to the police. The fact of underreporting of crime is undeniable. What's unknown is whether a change in the level of underreporting is responsible for the trends we see of falling crime.

So crime is underreported, but how much of an impact does it have on the numbers? Not as much as conventional wisdom holds, according to him:

The real meat of the problem — in my opinion — is that if crime underreporting has, on the whole, gotten worse then does that mean the declines seen in the FBI data are wrong? I would say ‘probably not’ for three main reasons.

And:

Smaller places appear to be following the same declining trend as bigger places in the preliminary quarterly data suggesting that the trend is real and not due to more people refusing to report crimes that occur. It's easier to explain away underreporting in big cities, harder to believe that people are also underreporting crime less frequently in rural counties and small cities.

We can't know for certain whether underreporting is actually worsening. The available evidence points to possible problems some places with possible improvements elsewhere which implies any impact on national trends is likely minor.

I can’t really argue too much with Asher on any of this, simply because of data gap required to produce such a disparity in terms of crimes reported and the declines recorded. The only way this could be is if victims of crime in large numbers decided simply to not report crime when they occur, but I think this is largely an impossible scenario.

Which leads to the next point - the matter of crimes, when reported, not being prosecuted, leading to people to underreport crime:

Perpetrators and victims are less likely to understand the exact figures — unless they read this newsletter! — but my guess is they intuitively know the odds of an arrest for any one offense are low. Whether it went up from 2 percent to 3 percent from year to year probably doesn't mean much for offenders and victims. Moreover, the City Attorney in Seattle has been vocal about trying more shoplifting cases which would, in theory, lead to less underreporting if the role of the prosecutor was prominent in whether an incident gets reported.

If underreporting is increasing, and that’s a big if, then I would think that clearance rates (which have been low and falling) are playing a substantially larger role than the charging decisions of a handful of local prosecutors. But my guess is that these low clearance rates are already baked into peoples’ decisions on whether to report a given crime so the declines since 2019 probably had minimal, if any, impact.

Again, I can’t argue with anything there. People don’t like being victimized by crime and will at least attempt to report even a relatively minor (a term I use loosely) incident. There’s one alternative possibility that must be considered, however: even when crimes are reported, no response is given, no report taken by police. It’s a phenomenon I’ve borne witness to and so have many others I know have experienced. If a crime is reported and the authorities don’t even make a record of it, did it happen? I’d wager to guess this is something which occurs daily across the country, though I’ll leave it open as to whether this actually has a noticeable impact on crime statistics.

At this point, it sounds like I’m over-analyzing what are very cut-and-dried numbers. Since I don’t have any hard data of my own to refute the latest numbers, I have no choice but to concede that crime has gone down over the last year or two. Still, we’ve left “historic lows” well in the past, nor do I believe statistics are the last word in this discussion. There’s just something missing from the data. Maybe it’s something which cannot be captured in numbers.

Experiences vary, but I think, overall, America isn’t a dangerous country. I’d wager it’s safer than France, for one. The U.S. does have crime rates that are elevated compared to much of the developed world, but it’s also true that most Americans aren’t criminals, let alone dangerous people. Again, it all comes down to what kind of story about the country you want to tell. It’s fashionable to say the U.S. is a violent country when you want to take it down a peg, compare it unfavorably to some other country, or promote gun control. Or if you want to make the ruling class appear more competent than they are, you can easily point to these numbers to show that they’re more than capable of creating a safe living arrangement. A third option is if you want to cut out the legs from under the political opposition and show them that only bigots and oppressors are worried about things like crime and how, when liberated from laws and rules, people will manage themselves just fine, making you wonder why laws and rules exist in the first place.

What crime statistics fail to capture is what America’s problem actually is. The problem isn’t that crime is out of control in this country. This is a narrative I’ve taken great care not to perpetuate - misdiagnosing leads to cures worse than the disease. I’d be happy to fight the perception that crime is skyrocketing any day in order to get people focused on the real problem.

Which is? It’s that crime isn’t properly dealt with to start. I employ the term “anarcho-tyranny” as an all-encompassing way of encapsulating the problem, but it’s not just about how the government deals with crime - it’s about our society’s entire attitude towards crime and disorder. We seem to have taken the inevitability of crime to a logical extreme, where we deliberately take steps to avoid preventing it, or outright find ways of rationalizing it, thereby encouraging it. Even among the law-abiding public, there are many who regard anti-crime measures as not worth the trouble, unjust, or as the source of crime itself. Few people genuinely “like” crime, but we’ve gotten to a point where we cannot even bring ourselves to notice when it’s happening and to say aloud, in public, “That’s wrong, that needs to be fixed.” If anything, to say so puts you at odds with public sentiment.

Even when criminals are caught, charged, and found guilty, the consequences never seem sufficient. Some would say taking a punitive approach doesn’t fix the problem, but clearly, giving light sentences doesn’t fix it, either. It’s pretty obvious crime isn’t just a policy problem, but a cultural one. Our culture, or at least parts of it, cultivates a lot of criminals and when anyone suggests we bring the hammer down on them, those voices, how many of them there might be, are drowned out by those who oppose on civil rights and equity grounds.

For the sake of brevity, I won’t belabor the point; it’s something I’ve written about extensively since I started this blog. If one wants to get super-specific about it, then no, crime isn’t the issue. Disorder is. Jeff Asher made note of the smash-and-grab robberies that have become emblematic of the recent upswing (followed by downswing) in crime, regarding these as outlier events that people wrongly make too big a fuss out of.

But really - before, say 2020, how often did these events happen? How often do you recall seeing such events covered in the media? No, media coverage doesn’t equal reality, but the media doesn’t cover events that don’t happen, either. If you didn’t see it before 2020, it’s either because it wasn’t covered (doubtful, since such stories would undoubtedly draw great interest) or because it wasn’t happening.

People aren’t concerned about smash-and-grabs because they happen often. They’re concerned about it because they’re emblematic of the world we live in today. A world where one or more people can march in, destroy displays, swipe large amounts of goods, many of them valuable, and march right out without anyone stopping them rightfully shocks and concerns people. The idea people shouldn’t be concerned about these incidents is a non-starter. We absolutely should be; this isn’t what we signed up for as citizens of civilization.

Look at this incident which occurred a few days before Christmas in Irvine, California, a city with crime rates as low as that of Japan and Singapore. Notice how they don’t even bother to cover their faces anymore:

https://twitter.com/IrvinePolice/status/1738300149695480225

Ask yourself and be honest: are we supposed to feel things are orderly or disorderly when these things happen regularly, even if the statistics show these incidents aren’t as common as believed? Is this what a safe, orderly society looks like? Are we really supposed to believe everything’s under control? Do you really believe this sort of thing has been happening at the same frequency this whole time and we just figured out a way to get it captured on video?

Why did crime decline the last few years, nationally, anyway? I know what isn’t the reason: better enforcement. Since 2020, the trend has been for police to be less responsive, in hopes of avoiding more George Floyd-type incidents. The reality is that even when people would prefer that police respond to calls and deal with crime, the people who think police are the problem are a louder and more powerful faction.

Which leaves only one explanation: like a fire, the crime wave which began in 2020 burned itself out. I hold to a theory that society has, at a given point in time, a certain capacity for crime. It depends on the economic situation, the political climate, and also demographics (i.e., the number of young males). When it all converges, crime increases markedly. Once that fuel has been used up, it declines. Criminals are either taken off the street or even killed, people run out of things to steal and destroy, society adapts, etc. I guess what I’m saying is, the damage has been done. For now.

Nobody should be patting themselves on the backs for the crime rate’s decline.

What To Expect In The Next 12 Months

I’m not a doomer. I hope everyone will have come to understand that by now. The decline in crime rates is a good thing and I hope everyone else agrees. I still believe there’s not only a lot the data doesn’t capture, but there are people who seek to exploit the numbers not so the public has a better grasp on reality, but to have them conform to a preferred alternate reality.

I don’t know whether crime rates will continue to decline. My take is that if we’ve been in decline for two years, then the betting man in me says we ought to continue expect declines. However, 2024 is an election year - in the last two election cycles, crime has spiked, typically followed by a period of decline lasting at least two years. If this pattern holds, there’s a strong likelihood we see an uptick in crime in 2024. If we don’t, it won’t necessarily be unprecedented, but the fact it’s a break from recent history, especially given rising internal tensions in the country, would certainly raise eyebrows, at least on my part.

As far as preparedness goes, don’t let people like Jeff Asher lull or shame you into thinking that crime is something you ought to be less cognizant of. No, don’t worry about crime - even if you lived in a place like Mexico, worrying constantly about crime is no way to live - but remember that even when America hit all-time lows in crime almost 10 years ago, we were still among the most violent countries within the developed world (even President Barack Obama reminded us of that occasionally). It takes only one incident to have your sense of safety and tranquility disturbed. At the personal level, crime casts a long shadow. As I often say, emphasize the personal over the political.

Likewise, remember that the local always trumps the national. By that, I mean it matters less what national crime trends are and more what your local trends are. If crime in your area is going up, then it doesn’t matter that crime across the country is going down. The same way you emphasize the personal over the political, emphasize what’s happening where you are above all else. Don’t worry about hurricanes in Florida when you have an earthquake to worry about in California, and vice versa. This is probably the best advice I can give you. If crime isn’t a big problem in your area, simply keep your guard up and go about your day. If crime is a big problem in your area, it’s time to batten down some hatches, reinforce your defenses, and be more alert and aware as you go about your business. The same way military units modify their alert postures depending on the situation, do the same for yourself and your family.

I realize I’ve said far too much about something which, on its face, is good news. I think we should all breathe a sigh of relief that crime isn’t getting worse in the country. We could all use one less crisis, after all, and nobody wants to become a victim of crime. It’s just that the statistical reality doesn’t seem to explain the increasing sense of disorder, which isn’t entirely a matter of perception. Going back to the 1980s, anyone who thought crime was worsening in the first half of the decade would be wrong to think so, but they would’ve been right to think crime was a problem because the overall incidence rate was still high. Two things can be true at once.

Crime Costs More Than You Think

Allow me to get one more thing off my chest before closing out.

Last year (2022), a writer name Ben Southwood wrote an interesting essay arguing that crime’s greatest costs aren’t apparent on the surface, suggesting that if you think you take crime seriously, you probably don’t.

The essay is worth reading in its entirety, but here is his main argument:

I think crime is underrated as a topic.

Crime is important because being victimised is extremely bad. People hate it. Even on top of the obvious costs, say if you lose a $1,000 phone, it feels humiliating and scary, shaking your faith in strangers and the world. This means that when crime does happen, it imposes large costs on people’s welfare: not just literally having stuff stolen, and not even just sustaining injuries, losing days at work, but deeper psychological harm. It means that people go to great lengths to avoid it, often in ways that have negative impacts on them and society at large.

Of course, crime is also pretty much inevitable, and a feature of all societies. It’s going to be impossible, with the best education, social programmes, and criminal justice system, to reduce it to zero. But it’s worth having a gauge of how costly crime is, so we can think about how important it is, and therefore what programmes it’s worth funding to reduce it, and how much effort we should spend on thinking about crime policy.

Southwood goes onto talk about the cost of crime in monetary terms. It’s an interesting argument and numbers do a better job than most things in capturing costs. But what drew the greatest attention for me was when he talked about the more intangible consequences of crime.

Here’s what they are:

I actually think the American problem is considerably bigger than this estimate, because this study only includes the costs of crimes that actually get committed. However, people try their damnedest to avoid being the victims of crime. This leads to many extremely socially costly behaviours.

Some of these have really obvious ‘macro’ effects. People who fear new neighbours have a substantial risk of committing crimes tend to oppose new development nearby, and to live in extremely spread out ‘sprawl’ suburbs, where sheer walking distance between places makes crime more difficult. What’s more, people in high-crime areas prefer to travel with metal shields around them at all times – that is by car – causing dramatically higher carbon emissions. By contrast ultra-low-crime Japan is tolerant of high density development throughout its cities, and rates of cycling, walking, and transit use are all extremely high, while carbon emissions are much lower.

You can aggregate some of these points by looking at the links between economic success and social trust, which is closely associated with crime.

But other effects are more ‘micro’. In a society with extremely low crime, people don’t bother locking up their bicycles when they go around town. Car rental companies need not impose laborious and strict checks and rules to prevent their cars from being used in crimes – a huge number of annoying regulations cover off rare edge cases. Landlords need not ask for large deposits. Women can walk about freely at night, including through poorly-lit parks.

Southwood’s essay reminds me of a video I saw over the summer. Someone had caught, on his doorbell camera, Amazon delivery drivers throwing packages onto his porch, ostensibly out of frustration at working conditions. Again, it was summer and it was probably hot and muggy. At the same time, I think we can all agree that throwing someone else’s belongings is hardly a justifiable response to such frustration.

The resident decided, instead of seeking accountability, to placate his delivery drivers. He left coolers full of bottled water out and he noticed the delivery drivers were suddenly less frustrated when they came to his residence and began to act more professionally. Whether or not that newfound positive attitude carried over to other residences that didn’t offer complimentary refreshments, nobody knows.

I think we can all agree that, at least in the short term, it costs us little to be kind and generous to others. I think we can also agree that, in the long term, this isn’t a sustainable way of managing social relations. Let’s talk practically - how long was this resident willing to keep this going? Was he going to leave refreshments out on his front porch all year long? I highly doubt that. Again, in the short term, it costs him little, but in the long term, it costs him a lot, since those refreshments need to be paid for. Then consider the mental gymnastics involved in effectively paying extra just to make sure delivery drivers do the bare minimum and not angrily throw packages like petulant children.

I wrote an entire essay about it, but “high-trust” societies aren’t the result of an abundance of kind and generous souls. And though besides the point, many of what we’d consider high-trust societies - namely, Japan - aren’t high-trust at all, at least not in terms of sentiment. They do have strong cultural norms they guard jealously, however. In either case, societies that give a lot also expect a lot in return. They don’t become nice places because they give away lots of free stuff, they end up giving away free stuff because they’ve cultivated a society where trusting strangers to do the right thing is a reasonable risk.

Does that describe America to you? How many people believe trusting a stranger to do the right thing is a risk worth taking?

Sure, Amazon drivers throwing packages isn’t necessarily a crime. But I think the way the resident in question chose to respond to such unprofessional behavior is a perfect illustration of how we as a society have chosen to approach crime and disorder. We fear confrontation and harbor an unwillingness to use violence against those who break the rules. Those of us who dare to confront or exercise violence are further victimized or prosecuted by the state for doing so. As such, we attempt to work around the problem, taking steps to avoid it instead of addressing it, even if that means spending our own money to encourage transgressors to behave themselves. Left unsaid is what happens when the freebies go away.

But Max, you spend all your time here talking about the importance of avoiding trouble! Yes, because at the individual level, your personal safety is 100% your responsibility and the best way to ensure that is to avoid trouble, not court it. But I’ve never suggested appeasing bad behavior, either. If anything, I’ve discouraged it. You’re under no obligation to make someone feel better after they show disrespect to you by tossing your property. Personal safety doesn’t involve compromise and appeasement isn’t compromise, either. You need to be dealing with a good-faith actor in order for compromise to work, anyway.

Furthermore we’re talking about managing social relations. In a place like Japan or South Korea, chucking someone’s package would be regarded as a serious social infraction and nobody would be offering you cold refreshments as a reward. Even something as simple as handing over money to a cashier with one hand is regarded as disrespectful and frowned upon in those parts. Americans have every right not to live in such a strict society, but my point is that good manners are a building block of civil society. That man offered cold bottled water to delivery drivers because in America, we’re not allowed to insist on manners from other “grown-ass men” nor are we allowed to point out bad behavior. Doing so could get you killed.

Jeff Asher lamented the fact nobody posts videos of when packages get left behind without incident, only the videos where someone’s package gets stolen. There’s a reason for that: nobody deserves extra credit for doing the decent thing, the thing you’re supposed to do. It’s one thing to be expected to be recognized for going above and beyond; anyone who expects the world to pat them on the back for doing the bare minimum is probably lacking in something.

The Floor Is Open

What do you think? Do you trust the latest crime statistics? Do you see a point in telling people they’re wrong to believe crime is getting worse and leaving it at that? Is crime getting worse in your area? What do you think 2024 holds?

Let’s talk it out!

UPDATE: Reader “Brian Villanueva” replies:

“The only way this could be is if victims of crime in large numbers decided simply to not report crime when they occur”

I think Asher is blowing this off prematurely, especially by (as you say) using 2019 as his baseline. Perception matters, and the perceptions of police response has changed enormously not just since 2019 but in the last 15 years.

Liberals publicly condemn calling the police as a racist act. 20 years ago, neighbors who saw police at the door of your Chicago condo would ask what was wrong. They may do the same today, but they'll also post photos on Instagram tacitly condemning your Karen-ness. To inoculate themselves from social media shaming, the victims only "report" may be on NextDoor.

(As a side note, I wonder if the use of "Karen" as a baby name has significantly dropped among college educated whites in the last 5 years?)

This is an interesting phenomenon I didn’t consider while writing up this piece. There definitely exists, post-George Floyd, a taboo of calling the police, especially among the college-educated, urbane, more cosmopolitan class. I’m sure Jeff Asher has statistics which show people don’t call police any less than they did before. Does that, however, rule out the possibility crime did increase, but the reports didn’t? I hope someone will point out if I missed something in Asher’s argument.

I think we all agree peer pressure is among the strongest of influences that exist. If you belong to a social class that looks at calling 911 as something “bigots” and “Karens” do, guess what? You’re not calling 911. Social status is a powerful incentive and precisely what’s at stake. Status is what grants you access to the nice things in life, keeps you gainfully, employed, and negative PR away. If being victimized by crime, absorbing the loss, and pretending it never happened is the price of maintaining status, that’s exactly what people will do. People respond to incentives, if you haven’t noticed.

More from Brian:

Meanwhile, conservatives, tending to be more suburban and rural and more attuned to high profile non-prosecutions (whether shoplifters or rioters) have decided en-masse to arm up and opt out. I have to be honest, my DA is pretty good here in CA, but I wouldn't call the cops for property crime. Heck, I probably wouldn't call them even if I shot an intruder, unless he died -- no choice since I don't have a backhoe (yes, I'm kidding, somewhat.) I don't think cops are evil or anything, but I don't trust the regime to take my side against the criminals.

Combine these two, and I think a statistically significant drop in reportage rates over the last decade is not only possible but likely.

I do want to say: I don’t recommend people not call the police. You should, even if you know full well they won’t do anything. If you don’t wish to call 911, don’t - file a report online, at a time of your convenience. Whatever you do, get the word out. Even if the police can’t do anything about it in the end, at least a paper trail will have been established and the department will likely log it as a crime, as long as a report has been generated. At this point, this is really our only play: add to the tally.

Get on social media, NextDoor, whatever, and let others know what’s going on. Some people may think of you as a “Karen,” but I assure you, there are sympathetic ears out there. And if being a Karen is what troubles you, the only way to fight the perception is to simply embrace the role and become that squeaky wheel. As I’ve said before, speaking loudly is, contrary to conventional wisdom, quite effective. You just need to be persistent.

If nothing else, establishing paper trails and being loud will ultimately work to your advantage if the day ever comes where you have to take action against a criminal, including the use of deadly force. It’ll show that you attempted to work through the system to address the problem and that you sought non-violent ways to prevent further victimization of yourself and others. Be careful what you say, of course, but in the world we live in, having a paper trail is a must for prevailing in the legal world.

Brian continues:

The Southwood essay is great. I especially liked this about Japan: “They don’t become nice places because they give away lots of free stuff, they end up giving away free stuff because they’ve cultivated a society where trusting strangers to do the right thing is a reasonable risk.” Yes -- exactly. I used to work in Holland and France. Eindhoven and Paris are a 3 hour train ride apart, but a chasm separates them culturally. Paris is vastly larger, more urbanized, multicultural... and far less trusting. Eindhoven women (at least 20 years ago) would leave their bicycles unlocked and walk through any public park after dark. Most Parisians would hesitate to do either. Some of that is endemic in a bigger city, but much is heterogeneous culture and low trust. Tokyo is a very large city, but Japanese women wouldn't hesitate to do either of these.

Ironically, the following TikTok video is making the rounds on social media. It was recorded by a French woman living or visiting South Korea. Watch to see her talk about how safe Korea is compared to France:

https://twitter.com/AsianDawn4/status/1739890055697793492

Of course, she doesn’t risk explaining why Korea is so much safer than France. That’d require confronting some obvious differences between the two countries (can you name some?) and nothing will place your social status in jeopardy more than to point out obvious facts. It’s for that reason these videos exasperate me - what are you trying to say, anyway?

Is the fact women cannot walk alone at night in France an indictment against France, French culture, or decisions French leaders have made? Why’s South Korea so safe? Did it just happen? Or is there something about Korean culture, or maybe their leaders chose not to make certain decisions, that led to such inherent safety?

The same reason you can’t just tell people “crime has declined” without explaining what one ought to do with that information, you can’t just say, “South Korea is safer than France” without explaining what this means with respect to what makes a society safe and functional. Nothing “just is.”

Last bit from Brian:

Which gets to something which ought to concern even progressives: the largest costs of crime (financial and psychological) are borne precisely by those groups considered the most oppressed in the intersectional hierarchy: minorities, the poor, and women.

It’s the topic of my next essay, but the immigration issue is a perfect example. For years, leftists have insisted illegal immigration isn’t bad enough to the point it adversely affects any of us. There’s a problem with using the “no harm” excuse as a way to shut down discussion, but leaving that aside, this is clearly no longer a minor problem and people are taking notice.

In Chicago, specifically, a neighborhood was introduced to 500 new arrivals. 500 is a drop in the bucket compared to how many have actually crossed the border, yet in a matter of weeks, it pushed residents to their wits’ end. These residents are primarily Black or even Hispanic. In some cases, they’re White, college-educated, cosmopolitan types, and they’re all losing patience.

It doesn’t take much.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

"The only way this could be is if victims of crime in large numbers decided simply to not report crime when they occur"

I think Asher is blowing this off prematurely, especially by (as you say) using 2019 as his baseline. Perception matters, and the perceptions of police response has changed enormously not just since 2019 but in the last 15 years.

Liberals publicly condemn calling the police as a racist act. 20 years ago, neighbors who saw police at the door of your Chicago condo would ask what was wrong. They may do the same today, but they'll also post photos on Instagram tacitly condemning your Karen-ness. To inoculate themselves from social media shaming, the victims only "report" may be on NextDoor.

(As a side note, I wonder if the use of "Karen" as a baby name has significantly dropped among college educated whites in the last 5 years?)

Meanwhile, conservatives, tending to be more suburban and rural and more attuned to high profile non-prosecutions (whether shoplifters or rioters) have decided en-masse to arm up and opt out. I have to be honest, my DA is pretty good here in CA, but I wouldn't call the cops for property crime. Heck, I probably wouldn't call them even if I shot an intruder, unless he died -- no choice since I don't have a backhoe (yes, I'm kidding, somewhat.) I don't think cops are evil or anything, but I don't trust the regime to take my side against the criminals.

Combine these two, and I think a statistically significant drop in reportage rates over the last decade is not only possible but likely.

The Southwood essay is great. I especially liked this about Japan: "They don’t become nice places because they give away lots of free stuff, they end up giving away free stuff because they’ve cultivated a society where trusting strangers to do the right thing is a reasonable risk." Yes -- exactly. I used to work in Holland and France. Eindhoven and Paris are a 3 hour train ride apart, but a chasm separates them culturally. Paris is vastly larger, more urbanized, multicultural... and far less trusting. Eindhoven women (at least 20 years ago) would leave their bicycles unlocked and walk through any public park after dark. Most Parisians would hesitate to do either. Some of that is endemic in a bigger city, but much is heterogeneous culture and low trust. Tokyo is a very large city, but Japanese women wouldn't hesitate to do either of these.

Which gets to something which ought to concern even progressives: the largest costs of crime (financial and psychological) are borne precisely by those groups considered the most oppressed in the intersectional hierarchy: minorities, the poor, and women.

I really enjoy reading your articles Max