An idea I’ve considered floating is to issue “update” posts regularly to discuss breaking developments related to a topic I discussed recently. This ought to save me the trouble of writing lengthy posts, but also fill in some of the dead air between posts. Your time is valuable and I want to make your subscriptions worthwhile; one of the ways I want to achieve that is by posting more regularly. I think these update posts are an easy way to do so. And though I intend to update existing posts as I’ve been doing thus far, some essays run so long, it’s not practical to do so. I could create a whole separate essay out of some of these updates!

With that, let’s get to some late-breaking developments related to things we’ve discussed here recently.

The Hits Just Keep On Coming

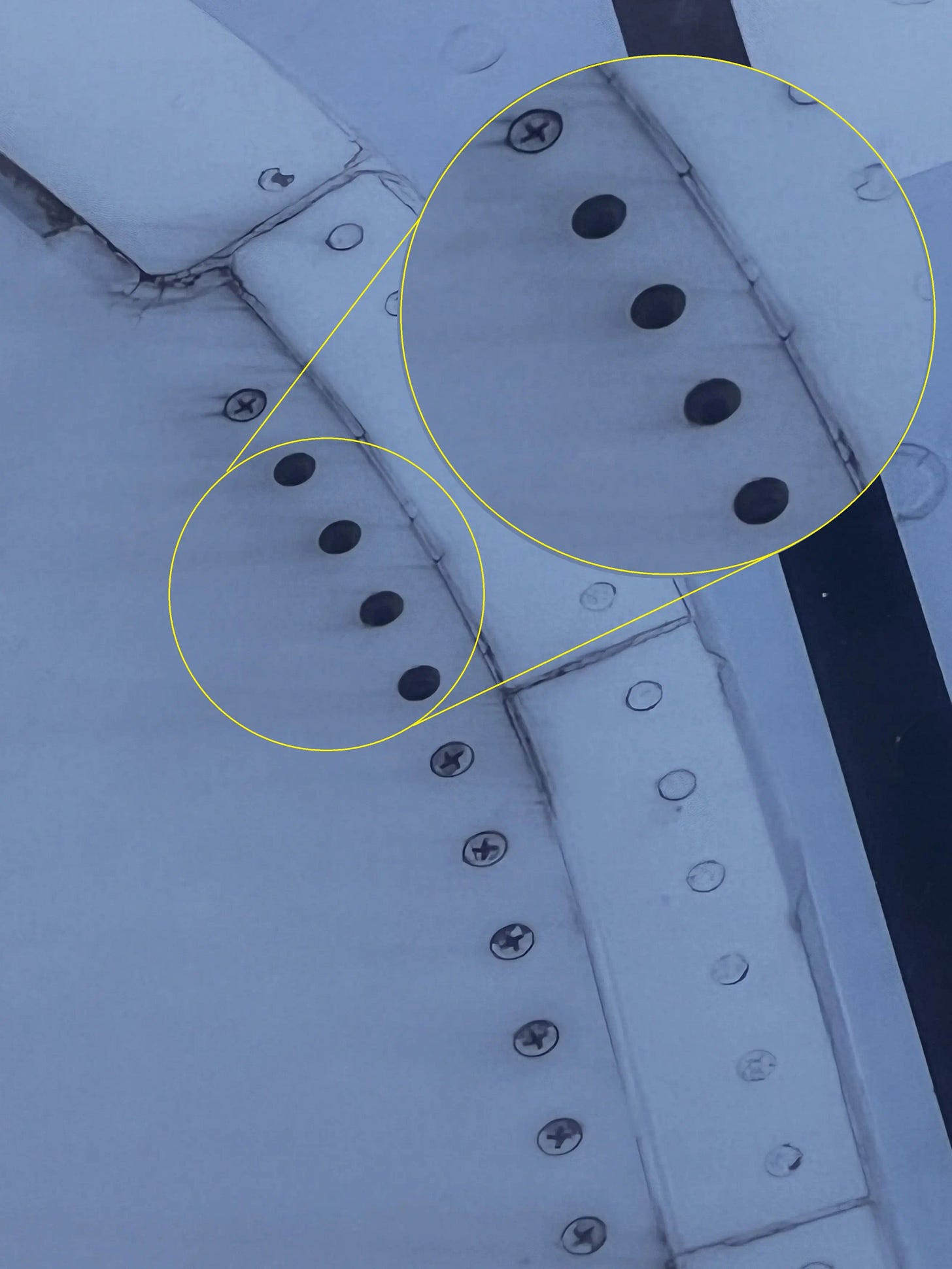

Would you want to fly on a plane that looked like this?

A New York-bound Virgin Atlantic flight was canceled just moments before takeoff last week when an alarmed passenger said he spotted several screws missing from the plane’s wing.

British traveler Phil Hardy, 41, was onboard Flight VS127 at Manchester Airport in the UK on Jan. 15 when he noticed the four missing fasteners during a safety briefing for passengers and decided to alert the cabin crew.

And:

“I thought it was best to mention it to a flight attendant to be on the safe side.”

Engineers were promptly called out to carry out maintenance checks on the Airbus A330 aircraft before its scheduled takeoff to John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, a Virgin Atlantic rep said.

Let’s face it - there are some people who wouldn’t have said a word. Nobody wants to be the one to say the flight needs to be delayed and surely nobody wants to delay their own flight. This passenger did absolutely the right thing, but it’s clear, when reading his account of the incident, that there was some hesitation involved. Let this be a lesson in see something, say something. If you think there’s something wrong with the plane, that’s worth delaying yourself and your fellow passengers over, even if it turns out to be nothing in the end.

In the case, it seemed as though it might very well have been nothing:

Neil Firth, the Airbus local chief wing engineer for A330, added that the affected panel was a secondary structure used to improve the aerodynamics of the plane.

“Each of these panels has 119 fasteners, so there was no impact to the structural integrity or load capability of the wing, and the aircraft was safe to operate,” he said.

“As a precautionary measure, the aircraft underwent an additional maintenance check, and the fasteners were replaced.”

I’m in no position to refute what the engineer says. It’s somewhat assuring to hear that nothing bad would’ve happened had the aircraft taken flight. At the same time, it’s unsettling to think something like that went missed during pre-flight inspections. From a passenger’s perspective, it’s definitely bad optics, not just for the airline, but for the industry as a whole.

For something like that to go missed is clearly a matter of negligence. Even if nothing bad would’ve happened, there’s a reason why things like workmanship matter: it assures people that the job is taken seriously and that one’s patronage is valued. It also demonstrates attention to detail, something that a high-stakes industry like aviation demands. This is coming at a time when the industry is under fire for a number of high-profile incidents, none of which resulted in loss of life, but would still make anyone think twice about flying.

Coming just a few weeks after the much-publicized incident aboard Alaska Air Flight 1282, the subject of my last entry, was this incident:

Once more, thank goodness nobody died. The Atlas Air flight wasn’t a passenger plane, either. But how many of these incidents are we supposed to bear witness to before we can begin questioning whether a larger problem exists within aviation?

The events preceding Space Shuttle Challenger’s demise in January 1986 (we’re less than a week from the 38th anniversary of the incident) really does serve as a parallel for what might be happening. Of course, I don’t want something to happen that results in tremendous loss of life. Yet there are warning signs flashing and I’m not sure the industry’s willing to take a break to figure out what’s going on, to see if they’re doing things that are putting lives and equipment at risk. The industry, along with so much of the economy, depends on planes taking off and landing daily without interruption. But I just don’t know what else ought to be done at this point.

It’s worth remembering the missing screws incident occurred in England, aboard a British airline, so we shouldn’t necessarily regard it as indicative of the state of flying in the United States or even globally. I’m sure there are a lot of near-misses that occur on a regular basis; some of it’s just bound to happen because to err is human. But there’s also such a thing as complacency; if we become too risk-tolerant, it results in us eventually accepting unacceptable levels of it. This is when the likelihood of disaster heightens.

I don’t know if this is what’s happening, that risk is being tolerated more liberally in the interest of keeping the planes moving. My personal experience tells me it’s not. But I also believe that these types of things eventually happen when people and equipment are constantly subjected to demanding work rates. Couple that with years of cost-cutting, running airlines becoming more and more expensive, it almost seems like the chickens are coming home to roost.

I still also maintain DEI isn’t what’s behind these recent incidents. DEI doesn’t help, no, but even as DEI isn’t new, there are lots of other things that’ve been going on for much longer that’s raising the risk of a major air incident.

Let’s hope the industry can get things figured out without having to shut the whole thing down. Hopefully, these close calls are alerting those running the airlines that safety is the outcome of good practices, not the natural state of flying.

Buyer’s Remorse

In my essay “‘Zoomer’ Discontent”, I remarked that homes are likely to be the most real form of wealth any of us will ever own. But home ownership is also becoming less prevalent due to high cost.

In Newsweek, they talked about how a landslide percentage of Millennials regret their decision to purchase a home:

Despite a housing shortage, many millennials have purchased homes in their 20s and 30s, just like their parents before them.

But for those who do, it’s often not the homeowner’s fantasy they once dreamed of.

A whopping 90 percent of millennials have regrets about their first home purchase, according to a new report from the Real Estate Witch. That’s a slight increase from last year's report, which saw only 82 percent say the same thing.

90 percent. Goodness. Certainly, there’s always going to be some level of buyer’s remorse when it comes to big purchases. But imagine that many people regretting purchasing the only thing in life likely to generate any capital for them. If that’s not indicative of how dire things have become, I’m not sure what else would suffice as evidence.

However, reasons for regret vary:

The regrets about the first home range widely. Around 27 percent said they regretted choosing a bad location, while 26 percent said they came to regret the bad neighbors their home is near. Just under that, 25 percent of millennials, which comprise those born from 1981 to 1996, said high interest rates caused them to have regrets about their home purchase.

So it’s not simply a matter of cost. However, we all know that higher costs correlate with better locations. Though it’s not clear what’s meant by “bad neighbors,” we also know certain locations, namely the ones with lower property values, do have the kinds of people you’d rather not share a street with. My guess is that Millennials are, as you might imagine, looking for the cheapest homes that are still in semi-reputable areas, but the number of these kinds of places are on the decline.

And yes, life is harder for today’s generations:

Because millennials hold far more debt than their elder generations, they are especially impacted by the high interest rates across the market. Baby Boomers, for example, were two times more likely to say interest rates have not affected their home buying plans.

This statistic arrives as 85 percent of millennials have some form of non-mortgage debt, with 22 percent owing more than $50,000 and 57 percent owing more than $10,000.

It’s also a situation that's getting worse, as millennials were 16 percent more likely than a year ago to owe more than $50,000 and 24 percent more likely to owe more than $10,000.

Access to capital is critical for both one’s own financial security and for the economy’s long-term health. Millennials are struggling to acquire capital, which means Zoomers will likely have it far worse. This cannot possibly be good for social stability.

At the same time, as a Millennial myself, I have to admit that we’re not the most frugal of people. We’ve come to accept luxury as a given and often use “I need to live a little!” as an excuse to spend money we don’t have. There’s also student debt, which probably accounts for some, but not all, of Millennial debt.

Yet the high cost of living certainly does make it easier to rack up debt. Debt absolutely makes it difficult to acquire capital, so whether it’s our fault or not, the end result is the same. For my part, my debt levels are virtually nil, I’m not a prolific spender, and yet home ownership is likely something I’ll never manage. Granted, I live in one of the most expensive metro areas of the country, but I’d never live here if I didn’t have a job here.

Nor are property values likely to go down:

Still, many millennials might be making a mistake if they decide to wait until interest rates fall down to historic levels.

“Many millennials put their search on hold thinking typical rates should be in the 3s, but what they don't realize is that the average interest rate since 1970 is 7.74 percent and there are low downpayment programs and interest-rate buydowns that can be negotiated with the seller,” Armstrong said.

Today, interest rates are below the historic average, and they’re expected to drop a few more times in 2024, so millennials are in the best position to act now, Armstrong added.

“After that happens, it will be extremely competitive as formerly hesitant buyers jump back into the market,” Armstrong said. “Now would be the best time to research low down payment programs and make a move before the competition heats up.”

Here’s the thing - interest rates are problematic because the cost of housing is so damn high:

But for millennials, even ignoring the interest rates, one such problem could lie in their ability to afford a home in the first place.

While the median home in the U.S. is $431,000, most millennials can't swing that. The study, which surveyed 1,000 U.S. adults who planned to buy a home during 2024, found that 57 percent of millennials planned to purchase a home that costs less than $400,000.

The housing market appears to be on a rebound, with mortgage rates generally declining despite continual home price highs.

In “‘Zoomer’ Discontent,” I mentioned that median home prices, had we remained at 1972 inflation levels, would be around half of what it actually is today. Americans are absolutely being priced out of home ownership and there’s no relief on the horizon. If interest rates are brought down and demand does pick up, then prices will continue to soar. The only thing that could bring prices down is an economic downturn, which would be problematic in many other ways.

This right here is the absolute state of affairs today:

To date, roughly 75 percent of properties on the market are out of reach for people in the middle class, according to the National Association of Realtors.

I don’t understand the real estate market as well as I should, so let me ask you all: what, if anything, can bring the cost of housing down besides an economic downturn? How on Earth can some people afford such exorbitant prices, enough to the point it keeps demand as high as it continues to be?

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

I agree with you about DEI not being the culprit. It is true that rewarding anything other than performance quality produces lower performance quality, but that's not why explicitly rewarding people based on their race or sex or sexual behavior is a bad idea. It's a bad idea because it's an assault on equal human dignity, the foundation of the Enlightenment. I'm not really a meritocracy fan, but since every system creates a hierarchy of human value, at least meritocracy has the advantage of allowing humans to move up or down in that hierarchy based on qualities that they can (to some extent) control and alter themselves. I can alter my work ethic, my education, my social skills, even my beauty... I can't alter my whiteness. Caste systems (whether in 18th century England or 19th century America or 20th century India) are inefficient and fundamentally immoral. Let's not recreate one here.

On the home ownership issue, the ruling class needs to decide on the narrative. Either millennials can't afford homes... or millennials hate the homes they bought. Which is it? Reminds me of Dreher's law of Merited Impossibility: that thing you're protesting isn't happening, and when it is, it will be a good thing.

It's not a good thing, but it may be a normal thing (and not just a "new normal" but the "old normal" too.) This chart illustrates this: https://www.longtermtrends.net/home-price-median-annual-income-ratio/ The advent of the 30 year mortgage and the broadly shared postwar GDP increases brought home affordability down to record levels in the 70's-2000. That was the historical aberration; now is the historical norm. As George Bailey says in It's a Wonderful Life: "That rabble, as you call them Mr. Potter, does most of working and breathing and living and dying in this town. Is it too much to ask that they they get to work and live in a couple of decent rooms with a bath?" For most of American history, the answer was "yes, it's too much to ask." A recession would help temporarily; reinvigorating the union movement would help; protectionist trade policy would help. What would help most of all though is loosening zoning rules and EIR costs so people can actually build more houses. (Who am I kidding -- I live in CA, the land that invented NIMBY.)

Newt Gingrich summarized that problem 20 years ago in a speech in Georgia. He was a WWII historian and professor before being elected to Congress. "December 1941 to June 1945. In 3 1/2 years we defeated nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and imperial Japan. Today it takes 17 years to add a 4th runway to the Atlanta airport. We are no longer a serious country." He wasn't talking about single family homes, but the logic applies just the same.

For my 2 cents, Max, I don't like updated old posts since they don't show up in my substack inbox. I prefer a new post with the updated information.

Regarding home ownership, with the benefit of hindsight you can always second guess your decision. My wife and I are happy with our home that felt crazy expensive at the time,

but in retrospect we should have dug a little deeper and bought a better house in a better location. We didn’t realize how cost prohibitive it is to move later on in terms of taxes, real estate commissions and moving costs. So you are more locked in than you realize into your first house.

We had to spend around $100k in the first 5 years on modest repairs and renovations (new roof and eaves, new furnace and AC, washer dryer, stove, repainting, replacing the basement carpet, etc). Basically things only last 15-20 years. Homes are also a ton more work than apartment living.

So home ownership is a painful experience in many ways, although I found it really nice to have a beautiful backyard during Covid.

I think that the impact of saving tiny amounts of money on mini-luxuries is overstated. If you save the cost of one coffee each working day, you’ll save a few hundred a year. Who cares.

It’s the big decisions that have a massive financial impact: how much to spend on rent, whether to buy a car, cost of vacations. cost of education, what job to get... best to spend more time on the big decisions rather than agonizing over small expenses.

People also underestimate the cost of the single lifestyle if you are dating and want to keep up appearances. Living poor is great if you don’t want a relationship with the opposite sex.

So I wouldn’t feel guilty over spending some money on yourself today, as opposed to saving for a tomorrow that may never come.