Misery Business

I’d say it’s a sure bet the people running in charge are aware: if Americans internalized how much trouble this country was really in, they’d have a mess on their hands.

Canada, the United States’ utopian northern neighbor, isn’t looking like much of a utopia these days.

An eye-opening story in the National Post details concerns on the part of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) that the internal situation in Canada is more unstable than it appears:

A secret RCMP report is warning the federal government that Canada may descend into civil unrest once citizens realize the hopelessness of their economic situation.

“The coming period of recession will … accelerate the decline in living standards that the younger generations have already witnessed compared to earlier generations,” reads the report, entitled Whole-of-Government Five-Year Trends for Canada.

“For example, many Canadians under 35 are unlikely ever to be able to buy a place to live,” it adds.

The report, which you can read here, is heavily redacted, itself offering little beyond what the National Post reported. It includes additional boilerplate Regime concerns, such as climate change, rising “authoritarian” sentiments, and extremism.

The fact that Canada’s national law enforcement agency (the closest American analogue is the FBI) assesses greater civil unrest in the coming years is a sure signal that the domestic stability so characteristic of the West, particularly the Anglosphere, for our entire lifetimes, may indeed be coming to an end. We’re probably not looking at becoming Argentina overnight, but 10 years from now, the discontent will be more palpable than ever. There’s always a certain segment of the population in any society prone to civil unrest, but the RCMP is projecting the unrest to be broad-based. Though not specifically highlighted, the implication is that the middle class will form a large component of this restlessness. A society can manage unrest from the lower classes, but middle-class unrest often portends revolution, because it’s the middle-classes which keep a society running and a state viable.

If that wasn’t enough trouble, tensions between Quebec and the Canadian government seem to be rising, not surprisingly over immigration. From the Montreal Gazette:

Premier François Legault on Tuesday threatened to hold a referendum on immigration if he doesn’t get what he wants from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Legault is pressing Ottawa for more power over immigration. Trudeau slammed the door on giving the province full control last month.

“Will we hold a referendum on (getting full power over immigration) eventually? Will we do it more broadly, on other subjects?” Legault said.

And:

He said Quebecers “have always been welcoming, will always be welcoming” toward immigrants. “But now we can’t do it anymore. Our capacity to receive has been exceeded.”

He said Trudeau recently admitted Canada has welcomed too many immigrants.

“It’s the first time he’s said that,” Legault noted.

The issue of Quebec independence merits a separate discussion, so the point here and now is that there exists tremendous discord within the developed world, including the Anglosphere, and that there’s no place on the planet where “it can’t happen here.” The strong economies of the U.S., Canada, as well as the UK have papered over a lot of problems, both lingering and self-inflicted.

I’ve always considered the U.S. to be distinct from the Anglosphere, but I’ve also found that what happens in Canada and the United Kingdom eventually happens here. Differences in economy and political culture means events don’t unfold quite the same way, nor are their problems the same as ours, but it follows many of the same trends. For example, the U.S. remains arguably the most religious, most Christian country in the developed world, but like the Anglosphere, is decidedly a post-Christian society. Racial minorities make up a smaller proportion of the Anglosphere’s population than the U.S., but race is a serious fault line for both.

Alex Garland, director of the upcoming film Civil War, which opened last week nationwide (read my review here), himself was motivated by the increasing level of discontent in both the U.S. and UK:

He began work on Civil War around 2018, observing the world and “feeling surprised that there wasn’t more civil disobedience” going on. Since those years saw protests over a range of issues – pro-Trump, anti-Trump, gun control, climate change and Brexit to name a few – I ask what, specifically, he was surprised that people weren’t marching in the streets about. This provokes a look of ferocious incredulity. “Is that a real question? I mean are you kidding? There were a holistic set of problems, globally. Not least in the country where I live [UK], or in the country I’ve been working [US]. There’s a lot to be very concerned about.”

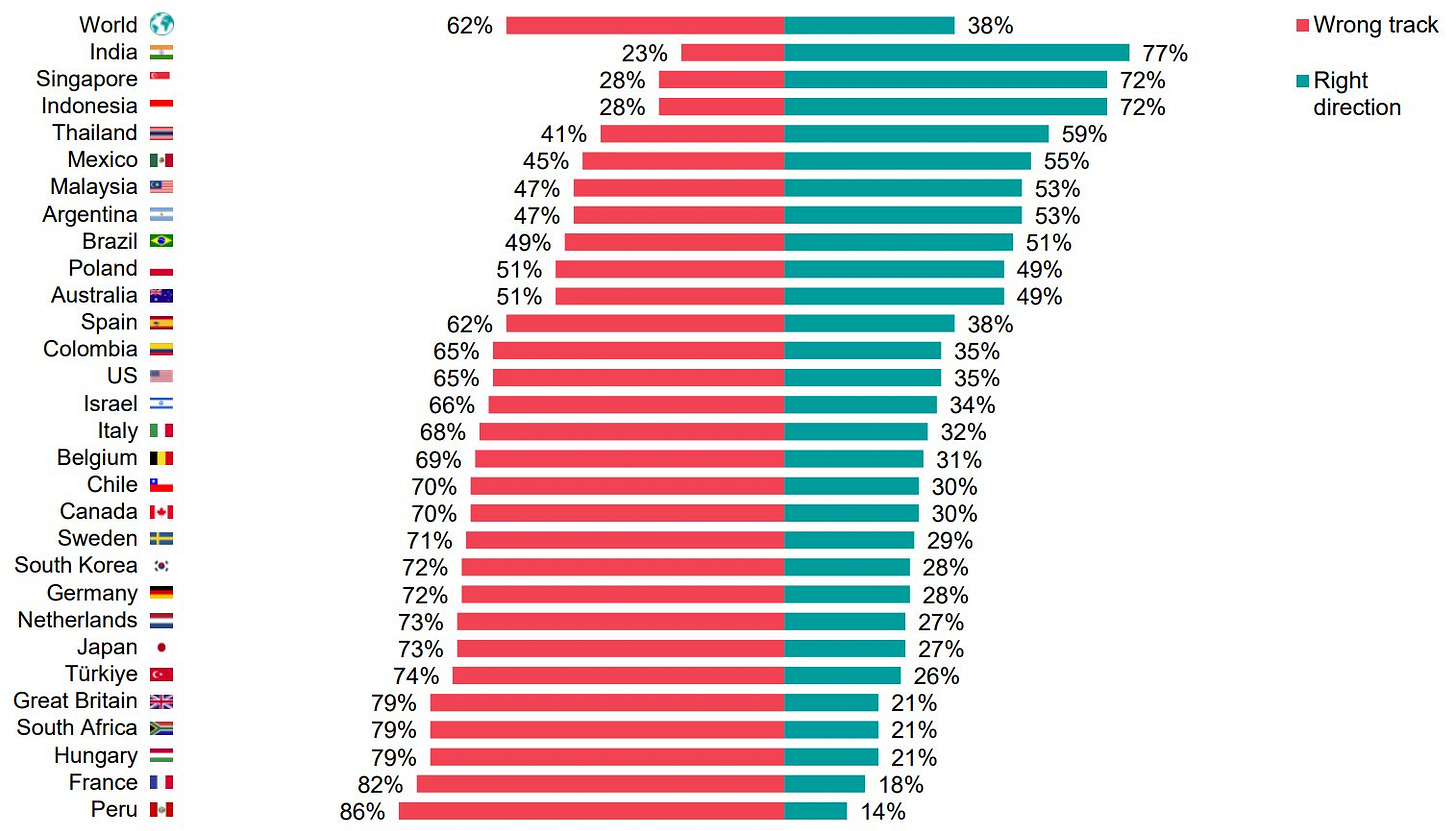

The level of discontent isn’t just perception. It’s reality. How bad is it? Take a look at these numbers:

Abysmal sentiments in the developed world, aren’t they? Before focusing on the places where discontent is high, notice not only how there exist few countries where people think things are headed in the right direction, but where in the world they tend to be located. Singapore is no surprise, at least not to me, but Indonesia is. Meanwhile, the majority of developing-world, middle-power countries like the Latin American superpowers and Thailand are more-or-less split down the middle. I have to wonder: is civil conflict more likely in a country where sentiments are polarized, or is it more likely in a place where the majority are unhappy with the direction of the country?

The academic answer, of course, is that civil conflict is the product of a myriad of factors, not just what percent of people in a given population think the country is headed to a bad place. For example, Mexico is, according to this survey, a deeply polarized country and has the scars to prove it with its ongoing civil war. But is its civil war truly the result of political division?

It’s not. Mexico’s civil war is the product not of political polarization, but of rampant crime and drug trade. Meanwhile, everyone in France seems to agree the country is going to hell and it’s very much on the glidepath to civil war, a topic I’ve delved into a number of times in this space. So it appears polarization alone isn’t enough to start a civil war, which I suppose is a good thing. Neither is a consensus on the state of the nation any kind of bulwark against it. As my prepper role model, Fabian Ommar, once said, “Civil war isn’t a fire waiting for a spark.” All it takes is one ignition source to set off an inferno, but if neither polarization nor concurrence is enough to light off a civil war nor stop it, there are clearly many different factors involved.

Look at how high the level of discontent in Japan and Hungary are - civil war isn’t even a talking point for either country. It’s quite clear: neither the level of discontent nor the degree of polarization in the country is enough to destabilize a society. So, what is?

Once more, the academic answer is that it depends on a convergence of factors. The high dissatisfaction in the U.S. and elsewhere are concerning, but on their own not entirely meaningful if not for a number of other concerning indicators present at the same time. And right now, all these factors appear to be converging.

Some have speculated that a report similar to the one issued by the RCMP likely exists somewhere within the great labyrinth that’s the U.S. federal government. As you all know, I don’t like to engage in loose speculation, but what I’ll say is that the U.S. military has long had plans in place to deal with internal unrest in the country. CONPLAN 2502, once known as “Garden Plot,” is this plan. Then there’s the Insurrection Act, the law which authorizes the president to deploy active-duty military forces within the U.S. for the suppression of disorder or rebellion. The active-duty military has been deployed many times within our borders throughout our history, so it’d be hard to believe the federal government hasn’t assessed the possibility of a middle-class revolt here in our country. This is especially since the Regime now regards anyone who expresses any opposition to them as “extremists” posing a threat to national security.

Even if there doesn’t exist a report expressing concerns similar to our neighbors in the Great White North, there are entire departments, an entire combatant command, dedicated just to dealing with problems inside the country. No doubt, sometime during the last four years alone, discussions have been held regarding the potential implementation of CONPLAN 2502, along with the president invoking the Insurrection Act. I’d say it’s a sure bet the people running in charge are aware: if Americans internalized how much trouble this country was really in, they’d have a mess on their hands.

This is the reality the U.S., Canada, and what remains of Western Civilization faces in the coming generations. The 2020s are just the beginning.

2024: The Beginning Of The End?

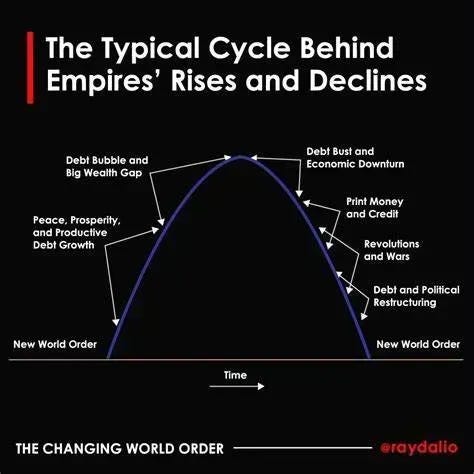

I’ve often asked the question: is America past its peak as a superpower? Or are we still at our peak? My go-to model on the question is billionaire investor Ray Dalio’s empire life cycle model, illustrating the typical lifecycle of empires:

It’s important to understand this model isn’t predicting the entire lifecycle of a country or civilization from birth to death. It’s the lifecycle of a country during its individual eras, specifically that of a superpower. It’s what Neil Howe and William Strauss called a saeculum, the Latin term for a single human lifetime. If we reach the end of Dalio’s cycle, it doesn’t mean the literal end of a country, not necessarily. It just means the end of that particular cycle of its overall lifetime and a country can go through this cycle many times throughout its existence.

I believe the U.S. is past its peak, but still near it, as our debt hasn’t bust yet and we’ve still yet to undergo a major economic downturn. That’s good news, for now, but it also means we’re at the beginning of a long descent which will bring with it much hardship. Gone is the predictability we once enjoyed, the privilege of being able to say, “Nothing ever happens.” There’s going to be a lot happening a lot more frequently in the years to come.

If you want to see what the decline looks like according to Dalio, watch this informative video he produced describing the empire lifecycle illustrated above. It’s over 40 minutes long, so you don’t need to watch the entire video now, but I do suggest you watch the section titled “The Decline.” It’ll help you understand what’s coming up the road and why people like me are so pessimistic about the future. I’ve set the video to start at the beginning of this section.

I think one of the three critical points he raises is that empires always opt to print its way out of its financial crisis. There’s literally no other choice. The state’s legitimacy depends on keeping the show going no matter the cost. The second is that a revolution or civil war inevitably occurs and violence results more often than not. Alongside internal conflict can often come external conflict, as hostile forces and rival powers seek to exploit the weakening of the declining power. Sometimes, though not always, an empire will kick off massive amounts of military spending in a last-ditch attempt to defend its global position, even at the expense of the rest of its economy. The third point is that a sell-off of dollars and American debt will typically mark the literal end of the empire, emphasizing the connection between superpower status and the world reserve currency. Printing large amounts of currency combined with the sell-off of foreign-held dollars and debt equals hyperinflation. It’s the scenario so much of the prepper-survivalist community spends significant bandwidth preparing us for. Put simply, if hyperinflation kicks in, it’s the end of our country as we’ve known it, so don’t get too excited about it.

The only question is time. The period of decline is something which can take years or even decades to fully unfold. There’s nothing that says it all needs to happen within the next four years. It’s a fairly safe bet that it’s not going to happen in 2024.

In an article written for Time magazine at the start of the year, Dalio explained the five factors which determine how history ultimately unfolds:

I believe that there are five big, interrelated influences that are driving the changing world order and that they tend to evolve in big cycles. They are:

how well the debt/money/economic system works,

how well the internal order (system) works within countries to influence how well people within them work together,

how well the world order (system) works to influence how well countries work with one another,

the force of nature, and

how well humankind invents new and better approaches and technologies.

Dalio goes into depth on each of these five factors. As a financial expert, he has a lot to say regarding #1, as you might imagine. Much as I talk about finance on this blog, I found much of what he was saying tough to follow, meaning it’d be tough for me to distill so readers can understand. I did, however, comprehend what he had to say here concerning America’s debt situation:

Meanwhile, the long-term debt cycle continues to progress toward greater levels of indebtedness (especially government debts), which will eventually be unsustainable and crisis-causing if not rectified. The deteriorations in government finances didn’t have much of a harmful effect because the incremental debt service expenses were heavily absorbed by central governments and central banks, because the faith in the government’s finances was maintained and because the Treasury managed its debt offerings well (e.g., by shortening the maturities of debt sold) to help fit the demand. For reasons I will explain more comprehensively at another time, I expect that if these policies continue to be used as they have been used and as they are projected to be used (i.e., excessive government spending and debt creation accommodated by central bank policies that keep real interest rates low and money and credit plentiful), it will in the long run create big financial problems, but that’s a topic for another time.

Of course, the question is “when?” When will these big financial problems finally surface? Nobody knows, but Dalio doesn’t seem to believe 2024 will be it. That’s not to say the economy is going to perform well through the year, however:

As for the economy in 2024, it appears likely that inflation won’t fall as much, growth won’t be as much, and interest rates won’t be cut as much as is reflected in the prices. More specifically, growth will slow, as the cash/savings pile that was built up from the big 2020 and 2021 stimulations is being run down and the interest costs on existing debt will rise as debts mature, which will require debtors to refinance their debts at higher interest rates. As for inflation, if there are no shocks from exogenous forces, I estimate that inflation will probably be about a percent higher than expected. Given that there is a lot of imprecision in my estimates relative to what will actually happen, I don’t have strong bets placed on them.

The last sentence is key. The recession so many keep anticipating has yet to happen, so who knows? Maybe they’ve figured out a way to kick the can down the road indefinitely. I doubt that’s the case, but my point is that until it happens, a recession, like most emergencies, are difficult to anticipate. It doesn’t mean you can’t prepare for them - financial prudence is a must even in the good times - but it’s that you shouldn’t let the possibility keep you up at night. We’ve all lived through recessions - I’ve lived through four in my lifetime - so all of us know what it’s like. We might’ve just forgotten.

What really concerns Dalio isn’t related to the economy, however. It happens to be the thing that makes me most concerned [bold mine]:

2. The Internal Conflict Force

I see this as the biggest single risk for 2024.

A number of countries, most importantly the U.S., are experiencing classic big internal conflicts over wealth, values, and power. The ways these conflicts are happening make it clear that they are in the classic Stage 5 part of the Big Cycle, which is the stage just before civil war (it is explained in detail starting on page 167 in my book [Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail]). This is when people align on one side or the other and fight intensely for their side or hide from the fight, and few people engage in thoughtful disagreement for the common good. In these times of irreconcilable differences, there is little respect for the existing order of rules and judges, so whether someone is guilty or innocent is judged and sentenced by intensely opinionated people (e.g., ”cancel culture”) rather than an evidence-based justice system. It’s a time when democratic orders are at risk of being disrupted because democracies require people to engage in thoughtful disagreements and follow a system that resolves differences by following rules.

Stage 5 of the Big Cycle is the “Print Money and Credit” phase of the empire lifecycle. I’m surprised to hear Dalio say that we’re in this stage, since the debt situation has yet to go critical. Then again, models are just that - examples. There can be overlap between events and there exist other factors which can exacerbate conflict at any time. Only when it’s all said and done can we place events precisely within each stage of the lifecycle. For now, it’s enough to say that we’re somewhere between the peak and the “Revolutions and Wars” stage.

More:

We are also seeing many other classic signs of Stage 5 behaviors such as politicians using their powers to weaken their opponents or even to threaten to jail them; unwavering voting along party lines even when the parties want extreme actions; pervasive lying, distorting, and taking political sides in the media; people moving to places to defend themselves against others who are different whom they feel threatened by; etc. This highly polarized, antagonistic mindset will be carried into the 2024 U.S. elections so it is difficult to imagine that either side will accept losing and subjugate themselves to the policies and values of the other side. Those policies and values are too abhorrent to those on the other side and respect for the rules is too low for those on both sides. I am not saying that we won’t adhere to rules and get through this with our domestic order system intact, but I am saying that it’s difficult to imagine how that will happen.

Unfortunately, this internal conflict evolution is transpiring almost exactly as laid out in the template explained in my book. When I published excerpts from the book online in 2020, including the prospect of some form of U.S. civil war, it was considered kooky. Then came the events of January 6, 2021.

When I wrote the book, lessons and indicators that I learned from history led me to estimate that the probability of some form of civil war in the U.S. was around 30%. That was considered an unrealistically high estimate. Now it is not. In fact, ~40% of Americans surveyed by YouGov think that it is at least somewhat likely that there will be a civil war in the next decade. I now estimate that the risk of some form of civil war over the next 10 years is about 50%, with 2024 being a high-risk year.

Personally, I don’t think this is as big a “both-sides” dynamic as Dalio makes it out to be. It’s pretty clear one side is responsible for the lion’s share of destabilization, but it’s also true that, with time, both sides will become mobilized. It’s unsettling to fathom, but the worst is still yet to come.

My own estimate is that the U.S. is very much on the glidepath to civil war, with the risk of it peaking around the end of the decade. This doesn’t mean a civil war is guaranteed to happen, it just means the probability of it occurring will be far higher than ever before. Public sentiment isn’t correct about everything, but it definitely matters that so many Americans aren’t only deeply dissatisfied with the direction of the country, but also believe a civil war is in the mix. Again, compare that to Japan and Hungary, where dissatisfaction is high, but nobody’s worried about a civil war. Where do you think a civil war is more likely?

I don’t share Dalio’s view that 2024 is a high-risk year, but I do believe this year and the next will mark a significant turning point that will significantly raise the likelihood of some of the more catastrophic outcomes for the country. Since 2020, we’ve tried to get back to normal, but it’s quite obvious now we aren’t living in normal times, not any longer. Our problems seem steady and manageable at the moment, but we are also at a point where we cannot afford much more in the way of crisis.

I laid out the road ahead in the finale to The Next 12 Months series earlier this year:

For the purposes of our discussion, let’s assume 2024 to 2025 will be a crisis period, likely to culminate in the political collapse of the U.S. as a superpower. Depending how quickly the country unravels in the wake of this tremendous shift, the civil war or revolution can happen anytime in the proceeding five to ten years. Consider the following a broad timeline of how America’s spiral into internal conflict will occur:

2024 - 2025: Crisis

2025 - 2027: Adjustment

2027 - 2028: Revolution

2028-?: America Divided

2024 into 2025 will be a major test of the Regime’s legitimacy. It’ll be so overwhelmed by crisis and internal discontent (as indicated by polling), it’s going to have to decide whether to double-down or back off. Those in power rarely back off in a time of crisis. Why would they? They’re fighting for their own survival.

I think 2025 to 2027 will be similar to 2021 to 2024, though in a far more unstable environment. Nobody can be outraged all the time and people will do what they always do: adapt to the new reality. If an economic recession or major financial crisis hasn’t occurred by this time, I’d be shocked. From 2027 to 2028, I see a major upheaval coming, what I refer to as the “quasi-civil war.” This is the moment our divide becomes entrenched, where the waters of warfare are tested, mostly through higher crime rates and civil unrest, along with political violence.

From 2028 and onward, we are in uncharted territory. Events beyond 2028 are entirely a matter of speculation, but I’m confident in saying that 2028, not 2024, will be the key election year. By then, politics will have become more existential, as leaders will have transitioned from managing our decline to figuring how to keep the peace and divvy up dwindling resources to a population of over 335 million. At best, I see present-day France and the UK as examples of what we can expect to face at this point. At worst, present-day Brazil and 1990s Indonesia or even Russia are crude examples of what we’re looking at.

What 2024 and 2028 will have in common is this: it won’t matter who wins the election. A big reason for this is because the president is only allowed as much influence as the managerial state permits. As long as those who are actually in charge remain so, nothing will fundamentally change. The significance of this year’s election is a matter of who’ll preside over America’s collapse as a superpower, while the significance of the ‘28 election will surround the question of whether the Regime will remain in power into the 2030s, how much more powerful they become, whether Americans demand a new regime, if any legitimate challengers arise, or whether America will even continue to exist in its current form into the new decade. It’s around the ‘28 election and the four years that follow where the risk of civil war will peak.

I still share Dalio’s reasonable sentiment that 2024 is an important year. It’s a year when many more of our problems will be laid bare and the fragility of the republic becomes undeniable. Nothing may fundamentally change, not until the election is fully resolved, but if nothing else, 2024 will be the year everyone realizes there’s no way to fix any of this.

Americans Are About To Overthrow The Government?

Malcom Kyeyune, no stranger to controversy, drew a lot of attention after stating the following:

Kyeyune is very much a thinker ahead of his time, which is both his strength and his liability. I’ve often said that commentators like him mentally operate in a world which may exist one day, but doesn’t currently. As I often dictate, stay in reality. But some make a living off rampant speculation.

I don’t share Kyeyune’s view that Americans are going to overthrow our government any time soon. I see neither a willingness to do so, nor is the government anywhere near as weak as it appears. The term “legitimacy” gets tossed around a lot these days like a magic word, but until the state can no longer enforce its dictates through violence, their legitimacy isn’t at risk. It’s not just a matter of citizens no longer liking their government. It isn’t even entirely a matter of the state being unable to manage crisis. It’s really a matter of the state being able to keep most of the population pacified. I’ve see nothing to suggest Americans can’t be held in line for at least another election cycle.

As for the fiscal crisis, until that debt bubble bursts, the show goes on. Frankly, I don’t understand why such intelligent people have a hard time grasping this fact. Obviously, the debt situation is unsustainable, but we’re not talking about what’s going to happen in 2034 or 2044, we’re talking about what’s going to happen in 2024. I’ve yet to see anyone provide any evidence that the bubble will burst this year. Until it does, to say so is wholly speculation, but you can’t even say that without receiving tremendous pushback. At some point, you can only conclude these people are invested, mentally or perhaps financially, in terrible outcomes.

Are we close to a revolutionary moment? Probably, but it’s still at least a few years away. 2024 America isn’t 1788 France and I’m not entirely certain its 1990 Soviet Union or 1917 Germany, either. I plan to talk about this more in an upcoming essay, but my line has held consistent throughout this blog’s existence: a lot of bad things need to occur before the really bad things occur.

Biden Changes His Mind On Illegal Immigration

President Biden used an interview with Spanish-language broadcaster Univision that aired Tuesday to send a massive signal that he plans to issue an executive order to dramatically limit the number of asylum-seekers who can cross the southern border.

Axios is told that while it's not final, such an executive order is likely by the end of April.

Why it matters: We're told there’s a fierce debate internally about the legality and politics of a Trump-like lockdown. But Biden, briefed on polls of rising voter anger, wants a dramatic step.

Between the lines: The provision Biden is eyeing would restrict the ability of immigrants to claim asylum, and doesn't require congressional approval, Axios reported in February.

Biden would use authority in Section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which gives the president broad leeway to block entry of certain immigrants if it would be “detrimental” to U.S. national interests.

He’d be taking a page from former President Trump, who has repeatedly leaned on that section.

Hmm! I wonder what changed?

How Are We Looking?

What do you think? What’s behind the malaise in the entire developed world? Do you think it’s better to be in a country where sentiments are split half and half, or to be somewhere where everyone agrees things are going badly? Do you share Ray Dalio’s prognosis for 2024? What about Malcom Kyeyune’s assertion that Americans are on the verge of revolution “pretty soon”? Why did President Biden suddenly decide there was too much illegal immigration?

Let’s jaw-jaw in the comments section.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

The young people of Canada not only cannot afford to buy many can’t even afford rent. Young adults staying with parents is now becoming common. I’ve never seen it so bad and I’m over 70.

Great video, Max.

"Earn more than we spend"

"Treat each other well"

Hmmm, I'm pretty sure I've read advice like that before. Some old book... "neither a borrower nor a lender be". And I'm sure some middle-aged, brown dude with long hair said something like "do unto others as you would have them do unto you". Too bad we got too smart for that book and that guy.

There was this white-haired guy in China a few thousand years ago who said something similar too. Perhaps the Chinese still remember him.

Dalio's 5 stability metrics in light of recent events are pretty funny:

1) Other than Germany, the entire G7 is over 100% debt/GDP.

2) Western internal political arguments have become theological. (ends vs means)

3) The world order is fraying as the US retreats (partially caused by #1 & #2)

4) A global pandemic just shut down whole continents.

5) This one is up in the air. Fusion power this decade... a new Matrix-frontier... maybe we kick tthe can another decade.

My training is also in econ as you know, and I concur with Dalio's comments on that subject 100%. However, you're wrong that there's no point preparing for hyperinflation. Diversify outside of dollars. Don't wait until capital controls happen; do it now. Ideally this means an actual foreign bank account (money physically held overseas) which is tough to setup. However, Everbank and Wise both provide easy ways to buy foreign currencies. For ideas where to park some money, perhaps the G20 countries with the lowest debt/GDP might be a good starting point (https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/government-debt-to-gdp?continent=g20)... maybe a large, Southern hemisphere one with oceans around it. Just a thought.

Finally, one of the things Dalio mentions in the Time article: "voters might eventually be faced with the question, if forced to choose, would you prefer a fascist or a communist?" This is the question of 2028 election aftermath. We're going to end up with a Lenin or a Mao or a Robespierre or a Franco or a Hitler. If I have to pick among those, I know my preference.