Should I Stay Or Should I Go?

The question of who is allowed to exercise violence legitimately is central to the existence of any social order.

DISCLAIMER: We here at this blog endorse only lawful and safe behavior. Always consult the relevant legal code first before you engage in actions with potentially serious legal ramifications. Take only reasonable risks and ask yourself first if you can live with the consequences.

While on vacation, I started reading a book titled No Retreat: Violence and Values in American History and Society by Richard Maxwell Brown. I’m still making my way through it, but it’s already been an eye-opening read. The book is an academic examination of the relationship between violence and American values. More specifically, it looks into why Americans have, at least until recently, been permitted such liberal (in a practical, not ideological sense) latitude in the use of force in defense of self and property.

The question of who is allowed to exercise violence legitimately is central to the existence of any social order. The whole purpose of civilization is collective safety; the whole purpose of government is to exercise violence on society’s behalf. If the government isn’t willing to do so, then it has no reason to exist. It’s this question that’s being asked in real-time, as governments throughout America and the West fail, often maliciously, at its one job.

The same way all governments eventually trend towards greater centralization of authority, governments also seek to attain a monopoly on violence. The reason is simple. The question of who holds power in society is answered by: Who gets to use violence? What kind of violence can they use? When can they use violence? Long-term, a state can only remain viable unless it both centralize power and achieve a monopoly on violence. Obviously, this isn’t ideal for the citizenry, but a state which cannot effectively curtail violence is breeding anarchy; anarchy inevitably leads to state failure. Currently, the U.S. and the West is doing something seen seldom throughout history, which is to attain greater centralization of authority and a monopoly on violence, while courting greater anarchy. Longtime readers of this blog ought to know the term for this by now, but for the new readers, this is called “anarcho-tyranny.”

In No Retreat, Richard Maxwell explains the relationship between state monopoly on violence and the concept of “duty to retreat:”

And:

Here’s the key point: for the duty to retreat and state monopoly on violence to be tenable as a policy, the state must be capable of resolving disputes between individuals. The state cannot just retain the sole license for violence while failing to rectify conflict between parties and manage to keep the peace. That’s not to say such a society can’t exist - the U.S. is still here - but it should never be confused with an orderly society.

Nor should it ever be confused with a free, democratic society. A state that doesn’t protect life and property or prevents the citizenry from doing so themselves isn’t just failing in its main duty, it’s tyrannical. The U.S. may be freer and more democratic than many countries of the world, but sometimes it feels like Americans have every freedom except the ones that really matter: the right to defend life and property, along with freedom of speech and association, though the latter two are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Jeremy Carl explains how the question of who gets to use force isn’t just the most important question of all, it’s most important in a historical moment such as the one we currently find ourselves in:

The use of force provides perhaps the closest thing we get to a glimpse behind the mask. If war is in fact, as Clausewitz said, the continuation of politics with other means, then the question of force is perhaps the fundamental political question in any society—especially a society in crisis. It is here that the sunny euphemisms of the left’s bureaucratic quasi-tyranny must give way to the visible exercise of raw power. This is where the emerging regime flexes its strength; but this revelation is also a weakness, because power prefers to remain unseen and in the shadows.

It’s not the kind of thing you say in polite company, but governance is ultimately the exercise of force - violence. It’s a fact of life we’ve gotten away from, since the safety and stability civilization offers allows us to naively regard governance as a substitute for violence. In reality, all we’ve done is relinquish our propensity for violence and outsource it to the state. The more a society enters crisis, however, the more the state relies on blunt force to maintain power, reminding us all that the government is, ultimately, in the business of waging violence.

Since most of us obey the law, however, our interactions with the state rarely end in violence. No matter what Black Lives Matter tried telling us over the years, there’s just no need for force to be used in the face of compliance. But this doesn’t change the underlying dynamic of the state-society relationship. Try not obeying the law just once and see what happens. It’s a risk most of us are unwilling to take because the threat of state violence in response to non-compliance is a credible one.

This is how statehood works, but when abused, it can become a tyranny, something the U.S. and the West are increasingly becoming. America is, of course, unique in that it possesses a fail-safe of sorts to ensure the state doesn’t cross too bold of a red line.

It’s for that reason that fail-safe is constantly under assault by the Regime:

The Second Amendment is arguably the greatest defense against tyranny: the constitutional right through which, ultimately, we vindicate all of our other rights and ensure they do not just exist on paper. Yet it has long been a prime target for the emerging regime, which attacks lawful registered gun-owners because its ideological predispositions do not allow it to have honest conversations about the real sources of violent crime in America.

I don’t think we’re going to see a gun-grab any time soon. However, the state has been extremely effective at narrowing the parameters within which citizens can use force in defense of life and property. Jurisdictional nuances aside, using force in defense of property is effectively a no-no at this point. Use of force in defense of physical well-being is basically limited to situations where a person is on the verge of death or great bodily harm. This has been the case for a long time, but the difference now is that the perception of death or great bodily harm has to be bluntly apparent to third party observers (mainly prosecutors and juries) for the use of violence in self-defense to be justified.

For such a threat to be bluntly apparent, however, death or great bodily harm must be clearly and obviously imminent. That means someone needs to be pointing a gun at you or in the act of punching or stabbing you to be well within the parameters for the use of force. Unfortunately, this also means that by the time you’re authorized to use force, it could very well be too late. It’s one thing to be forced to have a wall at your back when defending yourself. It’s another to be forced to be under assault or in the process of getting killed when you’re finally allowed to fight back.

Then there’s also the politicization of violence. Our politics is strongly influenced by Marxism and the principle of “Who? Whom?” applies to just about every aspect of life. Instances of violence are increasingly judged on the basis of the identities of the parties involved, decreasingly so on the matter of who’s the aggressor and who’s the victim. Anyone who thinks this doesn’t have an impact on the outcome of these cases has no idea what’s going on. It may not matter in terms of how the case plays out in court, but it definitely plays a role in whether the case goes to court at all and how the case is judged publicly. Imagine being charged, going to trial, and having everyone including the president talking about it. It’s not a good place to be.

I explained in my last post that America is entering an authoritarian phase in our evolution as a civilization. Unlike other countries, the struggle will not be between which side gets to exercise absolute power, but over how much power the government gets to have. The Left’s authoritarians seek to establish total state monopoly on violence, while the Right’s authoritarians will seek to diminish the state’s authority. Nobody likes being forced to choose sides, but in an authoritarian environment, choosing to remain “above the fray” isn’t going to be an option. The more power the state has, the more of a direct impact it’ll have on our lives. For Americans, the choice will be to whether to give the state more power to run our lives or to devolve that power to lower levels of governance or even more to the individual.

Given how many lives have been destroyed as a result of the state having tremendous power, you think it’d be an easy choice to make. That reality just isn’t apparent to many, unfortunately.

The Risk To Standing Your Ground

Coincidentally, a recent incident occurred which allows us to debate the matters of retreating versus standing your ground. The following incident occurred in Florida [WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT]:

Bottom line up front: this is way over the top. In fact, this is murder. I’m sure folks like self-defense attorney Andrew Branca can come up with some sort of defense for the shooter that could fly in court, but as preppers, we’re practical thinkers, first and foremost. In a practical sense, there’s no defense for what happened here.

Before discussing further, it’s important to disclose that Florida is a “stand-your-ground” state. The law is both among the most notorious and most misunderstood of any, so it’s important to have a good grasp of what it is and isn’t.

Here’s a short (7.5-minute) video explaining Florida’s stand-your-ground statute:

The key point is that under the stand-your-ground statute, there’s no legal requirement to attempt retreat from danger. If you’re the aggrieved party, you have a right to stand your ground and use reasonable force to defend oneself or others. By implication, that means stand-your-ground only applies in a situation where retreat was an option; it has no relevance in a situation where one’s back was already “to the wall.” Stand-your-ground was evoked by the media and the activist community in the 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman (which occurred in Florida), but the statute never actually played a role in the case because, as it turned out, Zimmerman was pinned to the ground by Martin at the time of the shooting, making retreat impossible.

As alluded earlier, stand-your-ground laws are highly controversial. They’re perceived, accurately or not, as “shoot first” laws providing wide latitude with respect to the use of deadly force. I don’t want to get too deep into that debate here, but I don’t think it’s too controversial to say that stand-your-ground laws do encourage the use of violence, since there’s no use in standing your ground during a dangerous situation unless you intend to use force to defend yourself. That, combined with a poor understanding of the law, can certainly lead to an excess of deaths, some of them totally unnecessary. Any proponent of stand-your-ground laws ought to come to grips with the fact that some people may end up dying needlessly as a result of such a statute. Humans do respond to incentives, after all. Evidence definitely exists that stand-your-ground-laws do increase homicide and gun violence rates, though its relationship with violent crime overall is less definitive.

At the same time, it shouldn’t be assumed stand-your-ground laws increase only the number of unnecessary deaths. It may very well be possible that stand-your-ground laws increase the number of justifiable homicides. Killing someone is obviously not a good thing, but neither is being victimized. When debating the pros and cons of stand-your-ground laws, one has to ask whether its preferable to trade off the lives of innocents versus that of offenders. It shouldn’t be a difficult trade-off to make, but since people have become over-socialized, it’s become impossible for many to fathom anyone besides the state using violence.

Of course, if the state utilized its monopoly on violence properly and did a good job of punishing criminals, we probably wouldn’t be having this discussion. Instead, it uses that monopoly to “keep the peace,” as if Americans are divided into warring tribes that’d try killing each other if not for the Regime. Ironically, the more powerful the Regime becomes, the more likely conflict becomes.

Back to the Florida incident. I’m having difficulty finding a news story about the incident, so if anyone knows more details about what happened here, feel free to post it in the comments section. What led up to the incident matters, but not with respect to the matter of stand-your-ground, however. It’s all about what happened in the moment those fatal shots were fired. There are two serious problems I see with the use of deadly force in this incident.

First, you’ll notice at 0:09, the eventual shooter draws his gun and either chambers a round or makes sure one is chambered. I have a feeling the prosecutors are going to zero in on this moment. Objectively, there’s no visible threat presented at that precise time and, therefore, little reason to draw a gun and ensure a round is chambered. The shooter will probably argue that he felt a threatened and wanted to be ready to respond, but then he’d have to be able to explain in detail what he felt was so threatening that deadly force needed to be put on the table. Consider the three elements of the threat triangle - capability, intent, opportunity - are they all present?

Once the eventual victim steps onto the shooter’s property and starts throwing punches, a threat definitely exists. But does it rise to the level of requiring the use of deadly force? Punches can be lethal, but again, look at the situation objectively - the punches don’t land very hard. The law doesn’t require the victim to retreat in this moment, but this is also where the stand-your-ground statute is most misunderstood: it doesn’t mean a violent response is instantly warranted. All other parameters for the use of deadly force must be met. All stand-your-ground permits is for the victim to stay exactly where he is and use reasonable force to stop the threat presented. Does the threat presented rise to the level of deadly force?

Prosecutors are also likely to make a big deal out of the roughly one-second gap between when the last punch is thrown and when the gun is drawn and discharged. At that moment, the aggressor-turned-victim is in retreat and the victim-turned-aggressor has plenty of time to decide whether or not shots need to be fired. We often hear that defensive shootings come down to judgments made in a split-second, but I think this instance is a tougher sell than most. I can’t read minds, but the impression I got was that the shooter was looking for a reason to fire upon the other man and he got one.

Once the attack has ceased, the justification for using force, especially lethal force, goes down tremendously, especially when the attacker is unarmed. Drawing the gun may be justified, but the shooter immediately opens fire. I often say that a gun should never be drawn unless the user is willing to shoot, but this presumes a threat exists that would justify the use of deadly force. If the shooter drew the gun, held fire, and warned the attacker to back off, and the attacker pressed on his attack or failed to back off, this would probably be a justifiable case of self-defense.

But since he opens fire instantly, he gives himself no leeway - he now has to explain that a danger to his life existed which made the use of lethal force a reasonable response. I’m not going to get into the part about how he empties the magazine into his victim after he goes down; that’s always a bad look. Technically, the law doesn’t permit you to kill anyone. It only allows you to stop a threat. Once the threat has stopped, that’s it - the defender must cease fire, if not retreat.

Of course, none of this may matter. How these cases play out in court doesn’t always depend on what makes sense. Consider this incident, also out of Florida [WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT]:

Two years ago decorated kickboxer Joe Schilling knocked out a patron named Baloba at a bar. He was sued. He claimed self defence. Below is the footage which speaks for itself.

If you watched the footage, I’m not so sure it speaks for itself, but anyway:

Schilling argued he believed he was about to be attacked and used force to defend himself. The court agreed finding that he was protected under Florida’s ‘stand your ground’ law which allows someone to use force, even deadly force, to defend themselves instead of retreating in the face of imminent harm.

The case turns on a split second. Before Schilling unleashed his punches Balboa is filmed doing what appears to be a head feint. The Court believed that this gesture was threatening and Schilling genuinely believed he was under threat of harm and acted reasonably. Another judge certainly could have decided things differently.

If you ask me, this was a totally unnecessary killing, even if by law, it was justifiable. I don’t see what sort of threat was presented that makes death an acceptable outcome here. I’m not even speaking morally, I’m speaking practically. The deceased’s only real transgression was disrespect; is it really something we ought to be killing each other over? Because there’s plenty of disrespect to go around.

One of Richard Brown’s main points in No Retreat is that much of the original reasoning behind standing your ground is related to honor. Back in the old days, dishonoring someone was considered a major social transgression and worthy of a violent response. I’m the first to say that there are far too many out there who don’t respect their fellow citizens enough and that they should be held to account for it. However, order comes before all. Responding violently to disrespect is necessary in terms of initially establishing order, but once order has been more or less established, the justification for continuing to kill out of personal offense diminishes. We create order out of chaos so it’s not necessary to kill everyone just to ensure ourselves and our loved ones one more day.

Obviously, we’re failing at that basic task as a society today, but as long as rule-of-law exists in a nominal sense, as long as we haven’t gone “Mad Max,” I’d suggest saving the killing for situations where one’s life is truly in danger.

Best Practices

I discuss self-defense often in this space, so there isn’t too much more I can add to the discussion I haven’t said already. Since this is specifically about the stand-your-ground statute, however, I’ll pose the question: If you live in a stand-your-ground state, what should you do? Should you take advantage of the statute if you find yourself in a self-defense scenario?

As always, the safe answer is: it depends. Again, stand-your-ground isn’t a blank check for the use of force. It merely removes the often unreasonable requirement for a victim to prioritize seeking safe refuge while under attack. While many, including the aforementioned MMA fighter, have been cleared under dubious circumstances thanks to stand-your-ground, it’s never a sure bet. Prudence demands we use force only when necessary to halt an attack, instead of looking for reasons to hurt someone. The temptation is difficult to resist, but one type of scenario can be covered by the law. The other cannot.

Even if you live in a stand-your-ground state (there are more of them out there than you may realize), prioritize avoidance over getting into a tussle. Violent encounters are chaotic to begin with and you may not have a whole lot of control over the outcome. You may end up using far more force than you intended to or was necessary to halt the attack, exposing you to legal troubles. At worst, you may end up getting seriously injured or even killed. Was standing your ground worth it, then?

If you do legitimately find yourself in a life-threatening situation, if retreat is an option and can be done so safely, do it. Stand your ground only in a situation where retreat would increase the risk of harm to you. For example, you’re not outrunning a bullet. Your best chance of survival may be to actually engage the gunman physically. On the other hand, when faced with a knifeman, retreat is likely the better option. Physically engaging a knifeman will get you slashed and stabbed, even if you ultimately prevail in the struggle. That said, a knife constitutes deadly force, meaning a deadly force response on your end is legally justifiable. If you’re facing a knifeman or someone possessing an overwhelming advantage in size or strength, you reside in a stand-your-ground state, and you have a gun, then your best chance of survival is likely to stay in place, draw your weapon, and prepare to fire. It doesn’t get more justifiable than that.

Let me say it again: if safe retreat is an option, take it! There’s not a single reward to be had in exchange for the risk. Only when safe retreat isn’t viable is when you ought to exercise your right to stand your ground. But never use it as an excuse to stick around and expose yourself to unnecessary risk when breaking contact was available as an option. Even in a stand-your-ground state, attempting retreat will help, not hurt, any case you ultimately may have for using deadly force in defense of self and others. When it doubt, do what contributes to your well-being at that precise moment in time. The answer may not always be obvious, but don’t overthink it, either - if you have to hurt or kill someone in self-defense, it won’t be any choice on your part at all.

Finally, I can’t stress this enough - have an understanding of the law. I realize most of us don’t have the money to consult with an attorney, but there’s plenty of free resources out there that can give you a general sense of what the parameters for the use of force are where you live. The only time you need to consult with an attorney or perhaps have one on retainer is if the likelihood you may end up using deadly force is higher than that of the average citizen. This would be someone who carries a gun on them when out and about and who’s otherwise not legally covered like a police office or security guard would be.

Never, ever, assume the law is on your side. The law is, at best, on one side only: theirs. At worst, they’re on the side of the bad people.

The Honor System Is For Those With Honor

We’ll close on a different topic altogether. Throughout the country, we see that many people still try to do right by their fellow countrymen, to be generous to others. For the most part, everyone tries to do the right thing, or at least be a decent person. At least, we want to believe this, because life is much easier when we can trust others. Either that, or reality is just too scary to confront. Whatever the case may be, many Americans still live their lives as though they can trust others.

Unfortunately, trust is a fragile thing, one that can easily be undone by a single person:

I once wrote an entire essay on the topic of social trust. America is already a low-trust society in the sense that the overwhelming majority of people don’t believe most people can be trusted. While Americans may know it to be true in their heads, their hearts haven’t fully accepted it. As such, many Americans live completely divorced from reality. There also still exist places in the country where social trust is still relatively high, though the number of these places are rapidly dwindling.

One of the ways all Americans will see societal decline manifest is in the arena of trust. In the future, being generous like the person who put out refreshments for delivery drivers will be an act of foolishness. The more Darwinistic a society becomes, the more kindness will be exploited for weakness. This is the essence of a low-trust society. Everyone likes free stuff and going by the honor system, we’d rather not have to have everything locked up and treat everyone like a potential threat. Eventually, however, it no longer becomes a choice. The reality of an honor system is that it requires people of honor in order to function.

In our current moment, anyone who shames Americans for being insufficiently generous to others is instead actually demanding we make theft and other social violations much easier for protected groups:

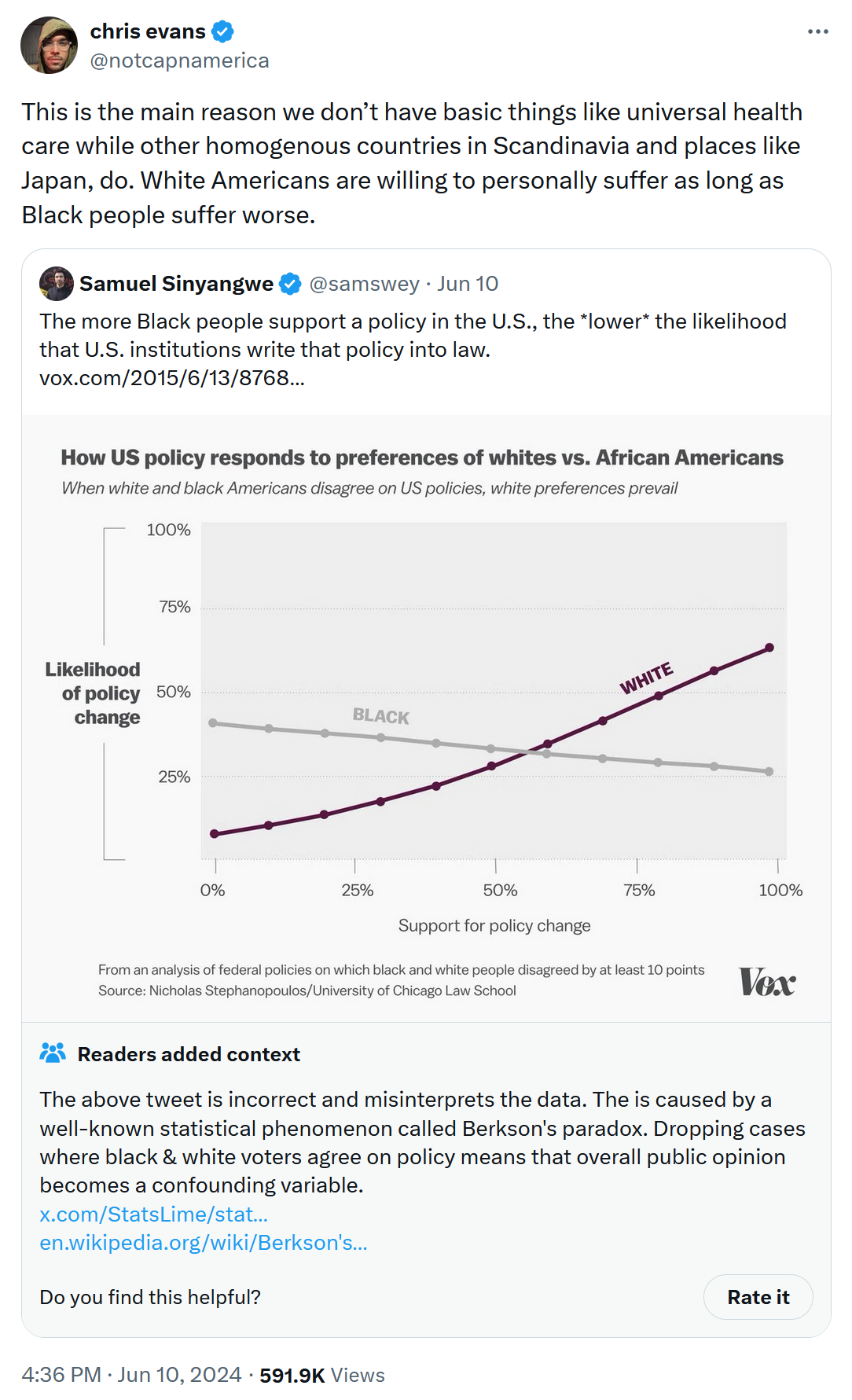

I’m not going to debate the substance of his argument, but let’s assume his premise is true: the more homogeneous a society, the more likelier we are to have nice things, like universal health care, generous welfare state, a high-trust environment. Does that not serve as an argument against diversity? No matter what our elites say, diversity isn’t a strength. It’s not necessarily a weakness either, but it does present unique challenges that don’t exist in a homogeneous society. Constant fine-tuning is required to manage relations between different peoples, which is why successful multi-ethnic, multi-racial societies often resort to authoritarianism. In many cases, authoritarian or democratic, one group often tends to have more power than the others. Often times, it’s the majority group.

There’s no need to get too deep into the weeds here, but in the future, as the U.S. goes into decline, if those in power insist on continuing to diversify the country, to force everyone to share living spaces, then we as individuals will need to make adjustments. The reason why high-trust societies also tend to be more homogeneous is because homogeneous societies have shared cultural values, social norms, and moral outlook. Diverse societies by their very definition don’t share much in common and require “rules of the road” imposed from up high. Maybe that’s where America’s headed and maybe we’ll find a way to make it work, the way a place like Singapore has. But that’s a good ways down the road.

For now, we need to come to grips with the fact Americans have very little in the way of shared values, whatever norms we’ve had are coming undone, and our morality being inverted. The most practical way to do this is to live as you would in a genuinely low-trust society. Quit leaving out free stuff - that’s for a moral people with honor - and expect nothing for free in return. Treat people with dignity and respect, demand nothing of them you wouldn’t want others to demand of you. At the same time, be ready to run from or fight anyone you come across.

Today, we find this woman’s instinctual reaction to be over-the-top and paranoid. In the future, however, it’ll become necessary for survival:

It’s not the way we’ve been accustomed to living. But this is how most of the world, even in some developed countries, live. One day, we’ll need to quit feeling ashamed of putting our safety ahead of signalling virtue.

To Retreat Or Not To Retreat? That Is The Question.

What are your thoughts on retreating in the face of danger or standing your ground? Do you think stand-your-ground laws are beneficial, or do they do more harm than good? Do you live in a stand-your-ground state? How has the law been applied where you live?

Let’s discuss in the comments.

Max Remington writes about armed conflict and prepping. Follow him on Twitter at @AgentMax90.

If you liked this post from We're Not At the End, But You Can See It From Here, why not share? If you’re a first-time visitor, please consider subscribing!

I will come back and closely read your article later but here are my immediate thoughts on "our right to retaliate to violence."

I reject both the idea that self-defence must be tempered in any way, and also the figment that we have an obligation to stand back and wait for the proper gun-toting government-licensed police force to provide our protection from harm.

Firstly the second part, that we wait for legal help when under assault, is easy to refute logically. It is impossible to have a police officer walking beside everyone , at instant beck and call. And further more, the legal system is only capable of arrest, prosecute, and penalize after the fact. To even consider the creation of a legal system that prosecuted for suspicion violate any and all legitimacy for law.

but point number one, our right to retaliate best approached from a pre-government viewpoint. In nature, all creatures do all they can to preserve their own lives, there being no world organized defence structure. Darwin rules apply; survival of the fittest. Humanity was no exception until the formation of social order changed things and it is the promise to curtail our ability to initiate force that underpins all social order.

Our brightest ancestors finally figured out that the proper role of government is to restrain those persons that cannot or will not live peacefully with their fellow human beings. Those who fully respect reciprocal rights in their fellow citizens need no restrictions on the actions-- those who do not,, deserve no freedom.

Finally, the recognition that each of us is a sovereign moral entity, that we live by our own moral standard, that what we do to others gives them the right to retaliate, is the basis upon which all human interaction hangs. Following that line of reasoning clearly sorts out the mess we live with today.

You can find a summary of the Canadian law of self defence here. The key word is reasonable. There is an interesting list of factors explaining what reasonable means, including whether there were other means available to deter the attack, but ultimately the question is whether your response was reasonable.

https://www.strategiccriminaldefence.com/faq/self-defence-laws-canada/

I wouldn’t think that a fist fight between neighbours or a drunk being annoying or aggressive to a large, trained professional would pass that test in Canada. The law even looks at the relevant size of the individuals involved.

I prefer this approach of looking at the overall situation to imposing a duty to retreat or stand your ground. That just confuses things and creates weird results sometimes.

In practice it seems the Canadian authorities recognize self defence very reluctantly and want to impose a pound of flesh on the person who protects himself, especially when someone dies.

So the reality is that, in all but the clearest cases, they will arrest the person and let the courts sort it out. That may lead to charges being dropped a few months later, but of course that is damaging and stressful in itself.

Without disclosing too much, our family had a case where an angry homeowner chased a teen who broke into his home under construction onto our property. One of the cops wanted to believe that the chasee was an innocent bystander, although eventually the cops reluctantly arrested him. (He was a fairly good looking white teen and it was a lady cop, FWIW.)

So the moral of the story is that the cops don’t like people chasing criminals, even if the cops have nothing to offer, and you have to be wary that the cops or prosecutor will believe the other side’s bullshit story even if you are in fact justified.